Shared Land, Shared Future: A Conservation Model for Africa

By Zig Mackintosh

When we think of wildlife conservation, we often envision vast national parks, multimillion-dollar budgets, and international organizations with large teams of researchers. However, some of the most powerful conservation stories are written by small-time operators working with limited resources, big hearts, and an unshakeable belief in their mission.

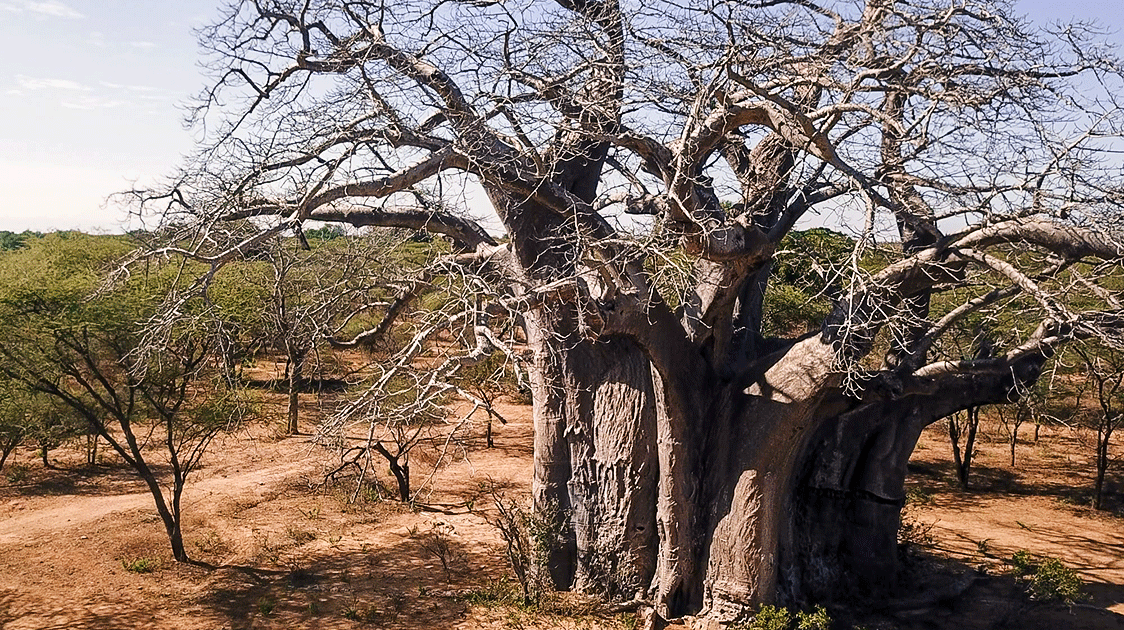

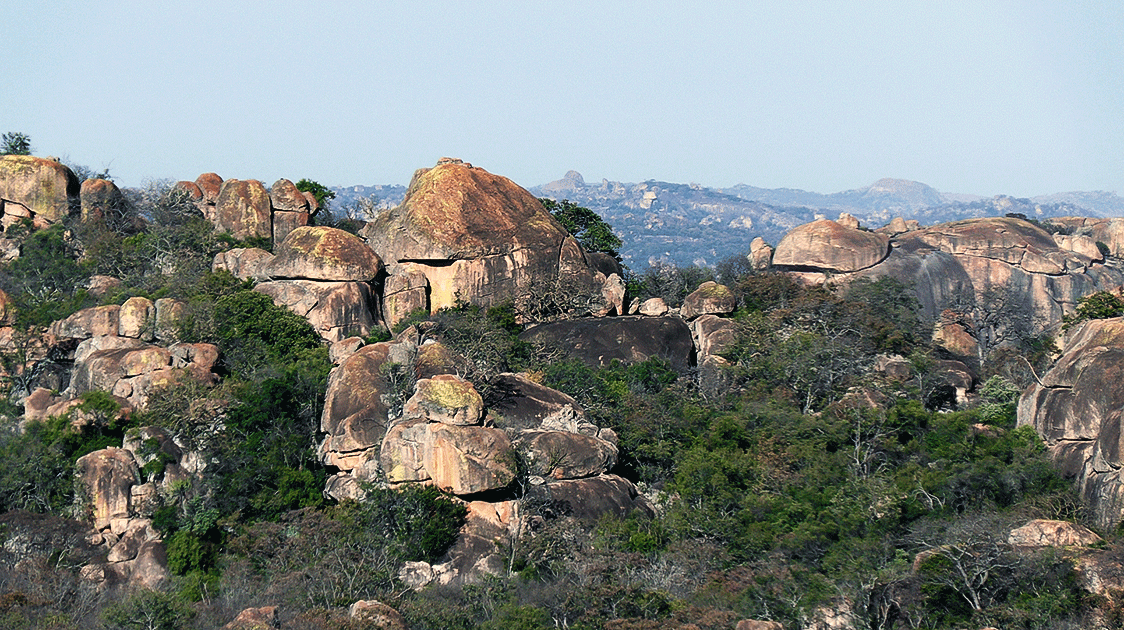

The breathtaking scenery of the Matobo Hills in Southwestern Zimbabwe, with its multitude of massive, round granite domes and gigantic boulders of various sizes balanced on top, has been sculpted over millions of years by the sun, wind, and water.

The hills, known locally as kopjes, fall into two main categories: the balancing castle copies, formed by rock splitting along natural lines of weakness, and the great smooth whalebacks, or dwalas, formed by curved joints running parallel to the surface.

This distinctive feature gave the region its name, Matobo, which means "bald heads" in the local Ndebele language.

The Matobo Hills have been inhabited for thousands of years, with archaeological evidence dating back to at least the Early Stone Age, approximately 300,000 years ago.

The San people occupied the area about 2,000 years ago, leaving a rich legacy of incredibly varied rock art. The art primarily depicts animals and human figures, often in complex scenes.

The Matobo Hills are home to a diverse array of wildlife, including the world's highest concentration of leopards. Research estimates one leopard for every five square kilometers.

The Matobo Hills are not just a natural wonder but also have spiritual significance for the Ndebele people.

Sacred shrines to their ancestral spirits have been placed within the hills to communicate with the mystical world.

The area was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003 for its distinctive landscapes and cultural significance.

Within the Matobo Hills lies a unique conservation venture that involves a partnership between private enterprise and the local people, promoting sustainable wildlife use, domestic livestock husbandry, and community upliftment projects.

When the Johnson brothers, Guav and Courteney, partnered with the communal land residents who had long struggled with poverty and limited resources, something remarkable began to take shape.

Together, they're transforming this rugged terrain into a flourishing wildlife reserve.

But this isn't a story of displacement or exclusion.

Instead, it's a tale of shared vision and mutual benefit. While the wildlife numbers have increased, the local community hasn't been neglected.

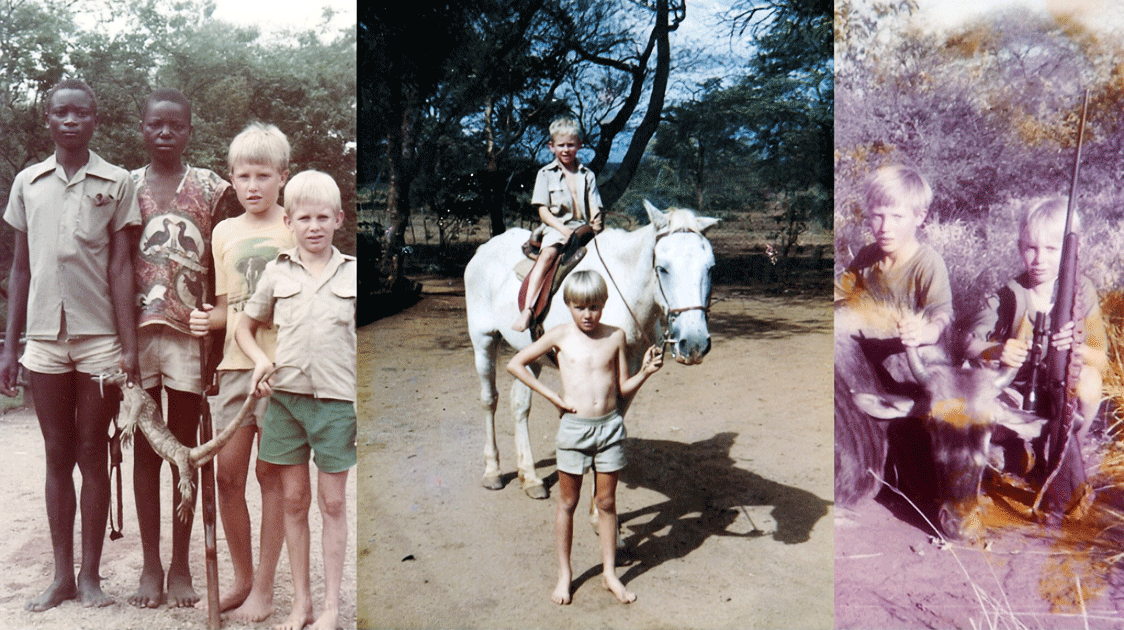

The Johnson brothers grew up in the area and attended high school in the nearby town of Plumtree. Their weekends were spent hunting, fishing, and exploring the region, so they had a natural affinity for the area, especially the Wilberforce ranch.

The ranch had fallen into disrepair, and the brothers wanted to rehabilitate it with the help of the neighboring communities.

They then initiated discussions with local community leaders, the district council, and the Ministry of Lands to establish a partnership with the community.

The idea was to fence off the ranch, increase wildlife numbers, and at the same time help the communities manage their cattle more efficiently on the other side of the fence.

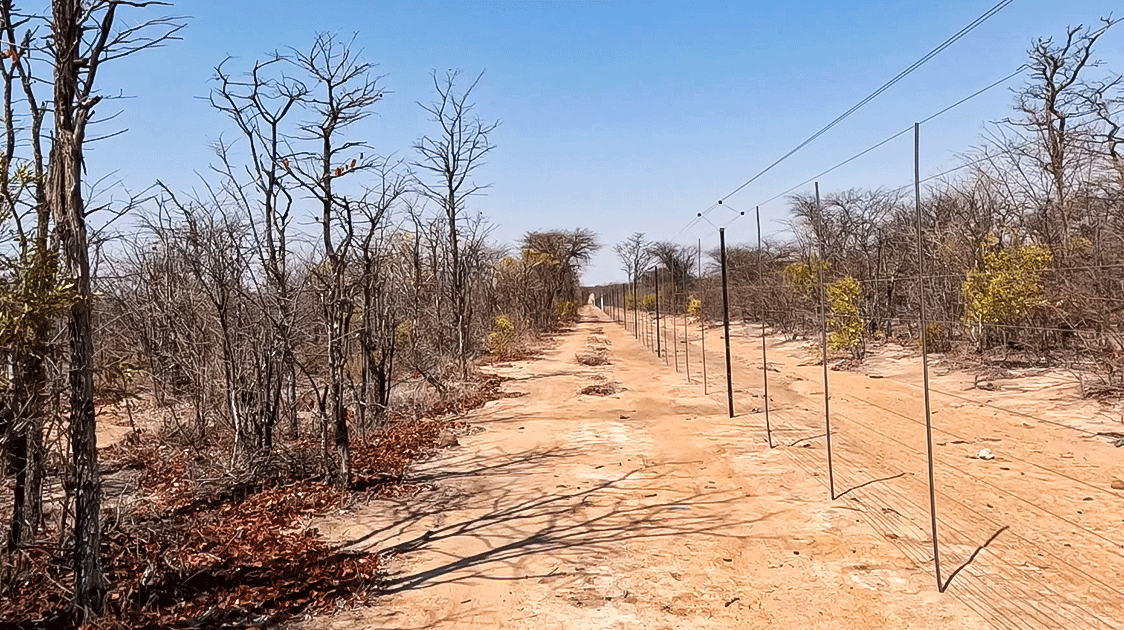

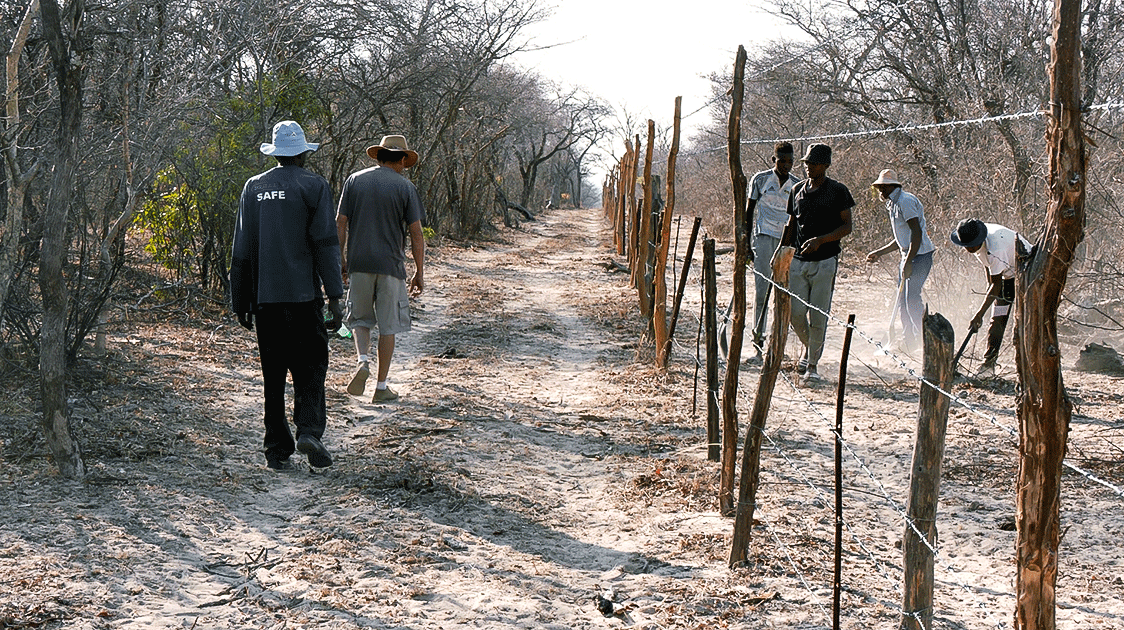

Keeping domestic cattle out of the designated wildlife area was essential for the ecosystem's recovery and long-term health. Without appropriate boundaries, grazing cattle would compete directly with wildlife for grazing resources; therefore, the first part of the project involved fencing off approximately 7,000 acres.

The Johnson brothers recognized the importance of demonstrating to the communities that there is room for both cattle and wildlife. Ultimately, their goal is to prove that game can be more valuable than cattle.

When they first started, the roads were nonexistent. They hadn't been opened in over 30 years, so a significant amount of work was involved in reopening the old roads and then installing new ones that would improve access to water points and facilitate anti-poaching patrols.

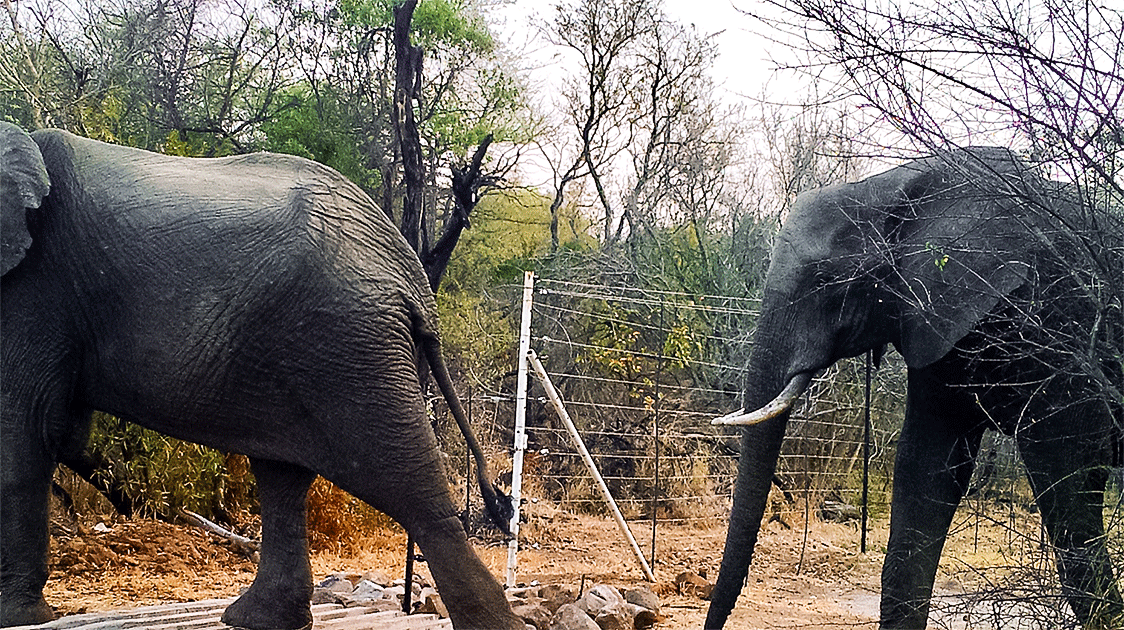

Gaps were left in the electric fence where they installed extended cattle grids to keep the cattle out of the wildlife area, while allowing access to the Mbakwe dam for elephants, predators, and baboons.

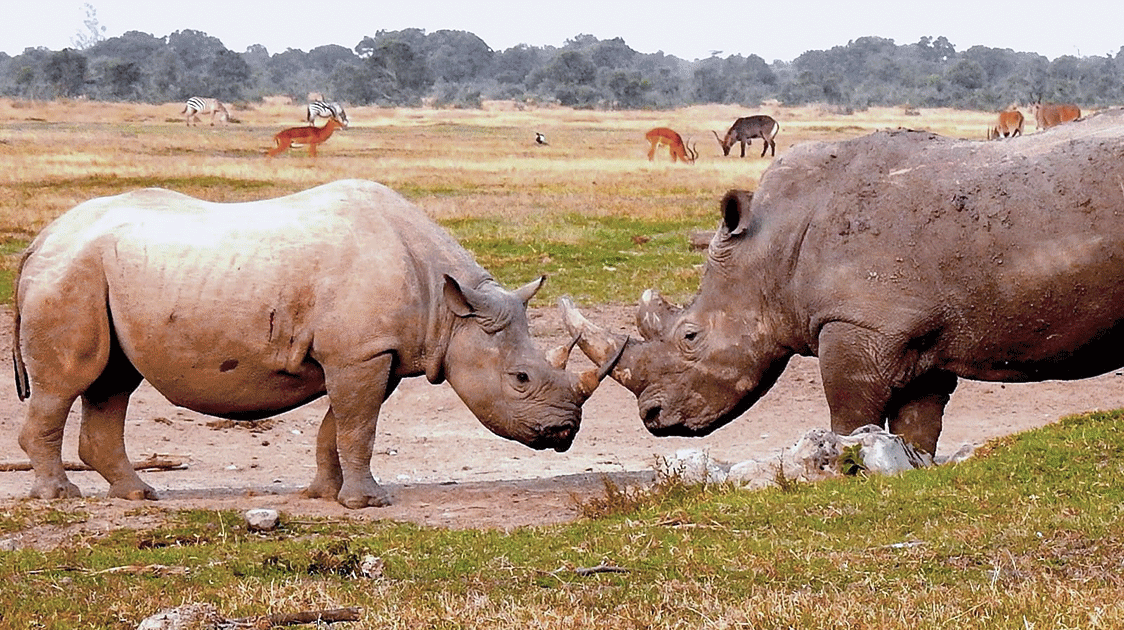

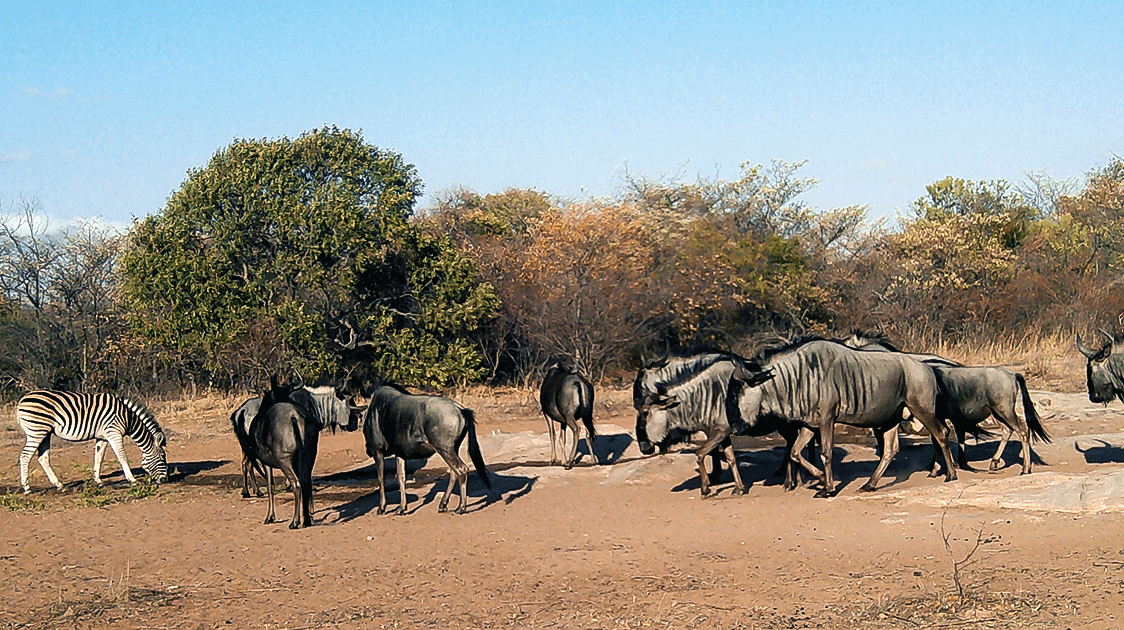

When the Johnsons first moved in six years ago, there was little wildlife apart from migratory elephants and some cattle-killing leopards. In the first three years, they didn't see a zebra, kudu were almost extinct, and a herd of impala would have comprised two or three animals.

The poaching was out of control. Once the larger species had disappeared, the poachers turned to using dogs and torches at night and nearly wiped out all the small game, including duikers, steenbok, klipspringer springhares, and scrub hares.

For the first four years, the anti-poaching operations were intense, and the wildlife numbers increased quite rapidly, not only through breeding but also through migration. Wildlife from adjoining regions found refuge in the reserve.

Photos from camera traps placed in strategic positions show how well the wildlife has recovered.

Giraffe and wildebeest have been introduced as part of an ongoing strategy to restock the reserve with wildlife. The plan is to introduce other species, such as eland, bushbuck, and waterbuck.

Illegal netting at the dam was stopped. The aquatic vegetation recovered, and the number of waterbirds increased significantly.

The dam water became clearer, and the fish sizes grew considerably. Fishermen are allowed access to a section of the dam, but only rod and line are permitted.

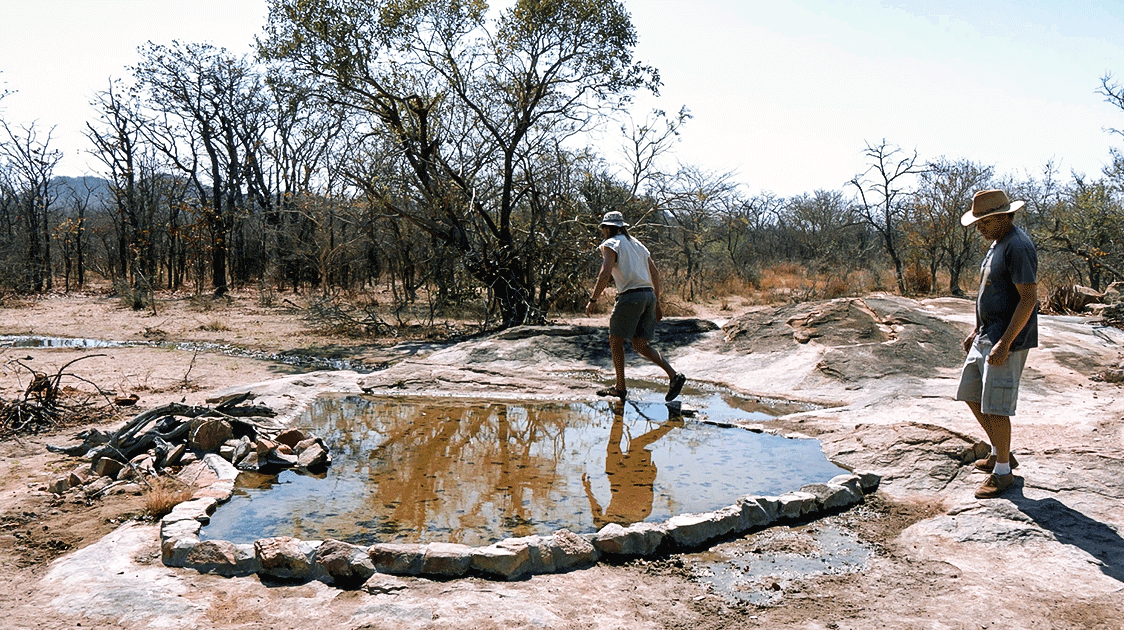

The provision of water was crucial for supporting the growth of wildlife populations. Strategic spots for artificial waterholes were identified across the reserve and are gravity-fed from a central reservoir situated on the hill above a productive borehole.

Elephants are notorious for digging up pipes to access water, so pipes to the waterholes were laid in the center of the roads to make it easier to find and repair any broken pipes.

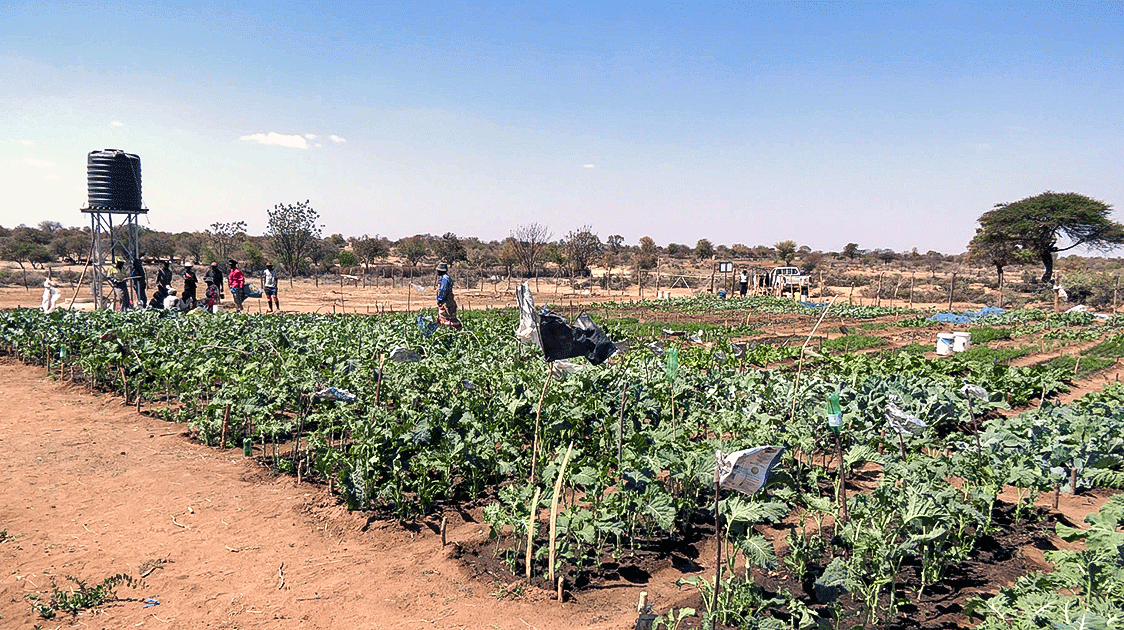

In the past, the community's only access to water was to dig in the river. A community vegetable garden was established when a borehole was sunk, and a solar pump and tank were installed.

The latest addition to the garden is an orchard with grapefruit, oranges, lemons, mangoes, guava, lime, and avocado trees.

In their early discussions with the community, the Johnsons recognized that livestock would play an essential part in the project.

So, they agreed to assist the community by providing clean drinking water for their livestock, which they had never had before. They provide the wire and the tools for the fencing in the cattle section, but the community must supply the labor.

The Johnsons didn't want a situation where the people just sat back, expecting everything to be done for them. Direct involvement in the project encouraged buy-in.

The success of the Wilberforce Ranch wildlife project can be measured by the fact that neighboring communities are eager to join the program.

They've heard firsthand how people are benefiting from the project and now want to be included.

If this happens, the reserve could more than double in size, growing from roughly 15,000 acres to over 30,000 acres as additional community land is added.

This unique model is proving that conservation doesn't need to be built on exclusion or a fortress mindset.

It can be built on:

- trust

- clear agreements

- shared land-use priorities

- consistent ant-poaching patrolling

- and visible community benefit

This partnership with the community has achieved what decades of neglect had undone: the return of ecological function to a landscape that always had potential.

It is a model that can be replicated in other parts of Africa.

Zimbabwean native Zig Mackintosh has been involved in wildlife conservation and filmmaking for 40 years. Over the years, he has traveled to more than 30 countries, documenting various aspects of wildlife conservation. The sustainable use of natural resources as an essential conservation tool is a fundamental theme in the film productions with which he is associated.