Can the Cascade from Wildlife to Cattle to Camels and Desertification be Prevented?

By Dr Daniel Stiles

In Volume 61 of Patrol, a staff writer published ‘The Inevitable Cascade: From Wildlife to Cattle to Camels, Comparing the Desertification of Arabia and East Africa’. I would agree with every word in the title except for the word ‘inevitable’.

I once called the camel “a living indicator of a dying environment.” Indeed, archaeological, geological, palynological and ethnographic evidence does support the assertion that the introduction of cattle and small stock (sheep and goats) pastoralism into subhumid to dry ecosystems under traditional management systems leads to land degradation, i.e. ‘desertification’.

There are systemic reasons why this occurs.

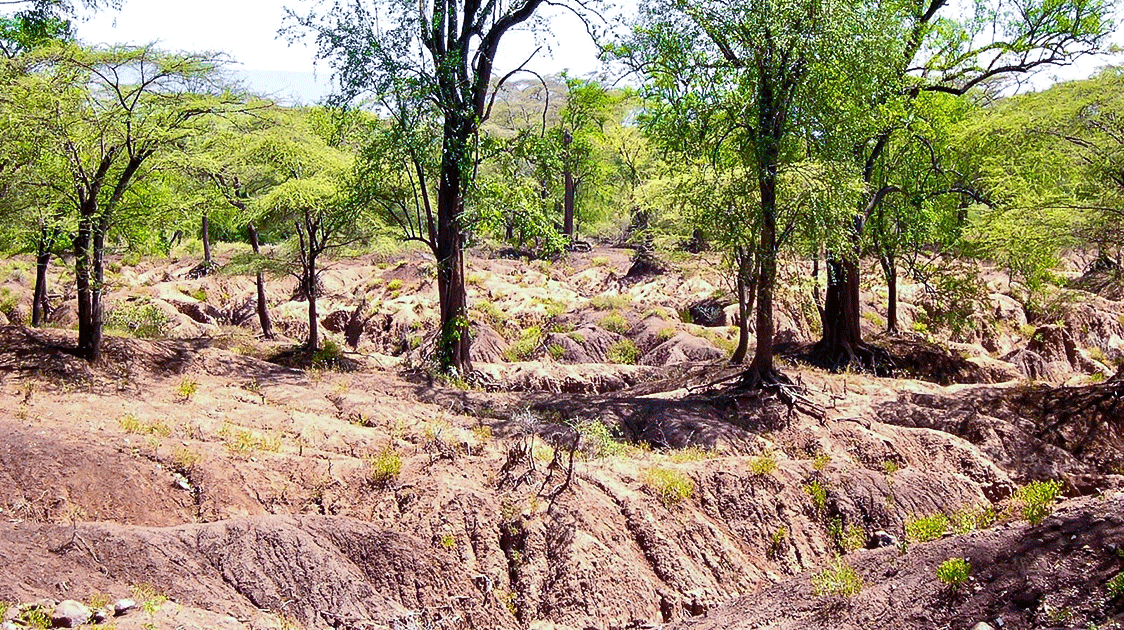

As the land progressively loses vegetation and soil from overgrazing and erosion under highly variable rainfall conditions, livestock populations and pastoralist food security experience periods of severe stress, accentuated by drought events.

Because pastoralists depend on livestock for subsistence and they constitute a “bank” for capital, the strategy is to maximize herd size. There are good reasons for this:

- Cows and small stock produce very little milk during dry seasons and drought periods, thus more milch animals are needed for subsistence.

- The more cattle and small stock a family owns, in general, the more that will survive a drought period.

- Livestock are used for many social and cultural purposes. The more livestock a family owns, the more politically powerful, secure, and respected they are; and

- Livestock is the best way to grow and store wealth.

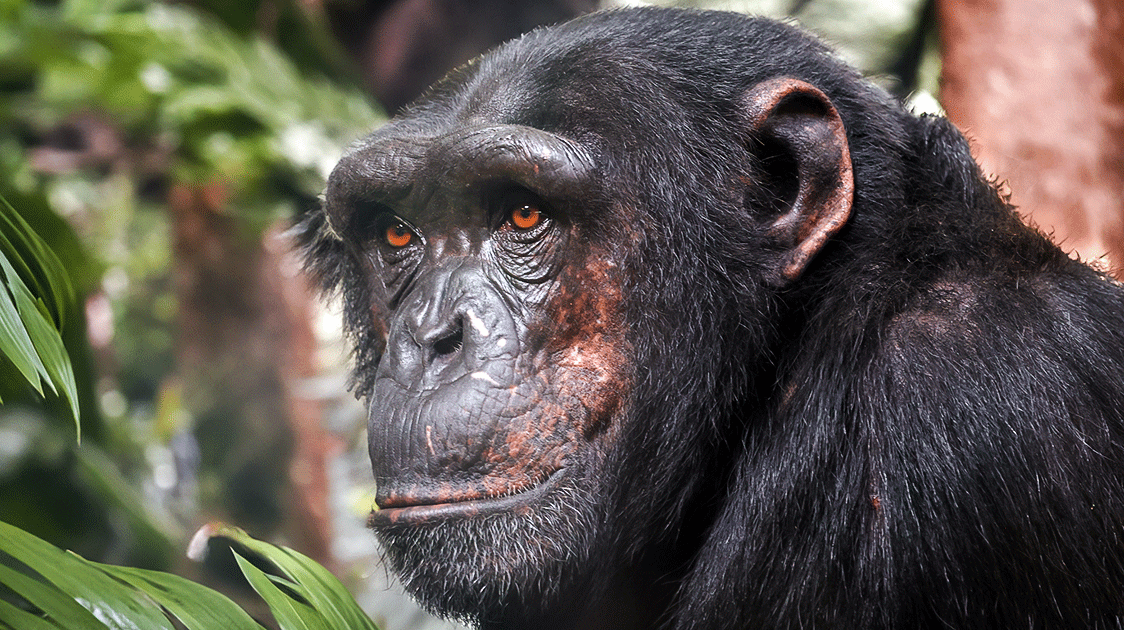

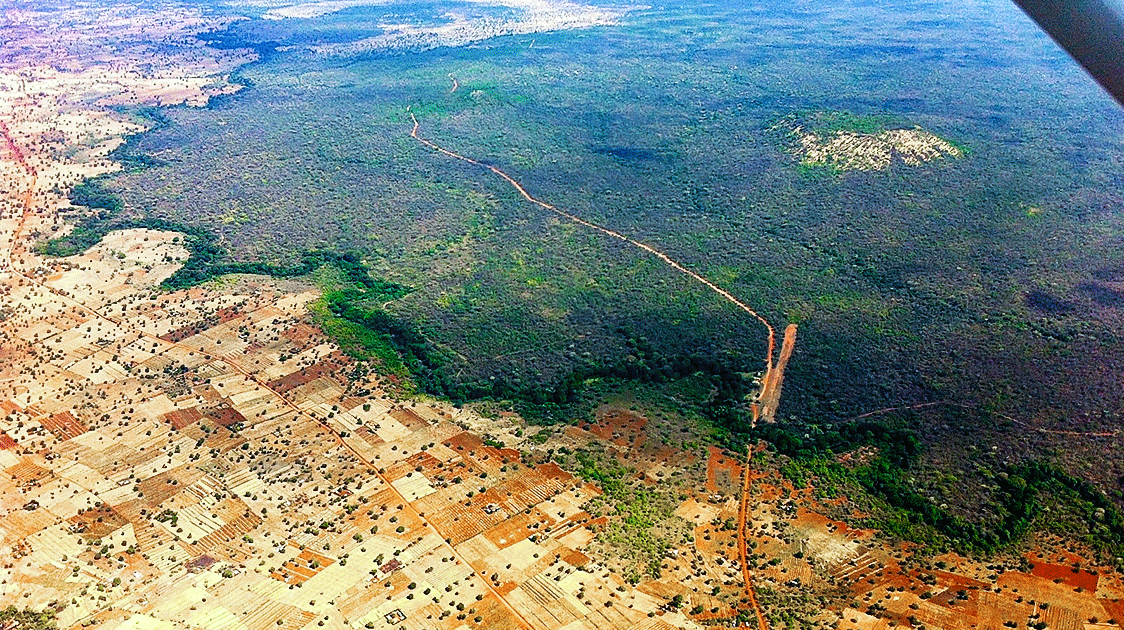

There has been resistance to the concepts of overgrazing, carrying capacity and desertification, but abundant evidence exists that large areas of land have changed from biodiversity-rich habitats progressively to biodiversity-poor habitats, usually taking centuries of time.

These days, climate change, with its increasing aridity, is often invoked as a cause, but this is too simplistic an explanation.

I am fortunate to have a background in archaeology, paleoenvironmental studies, ethnographic research on dryland pastoral peoples and practical work in the United Nations (UNEP’s Desertification Control section and the UN Sudano-Sahelian Office), so I have perspectives on the causes of land degradation from multiple disciplines.

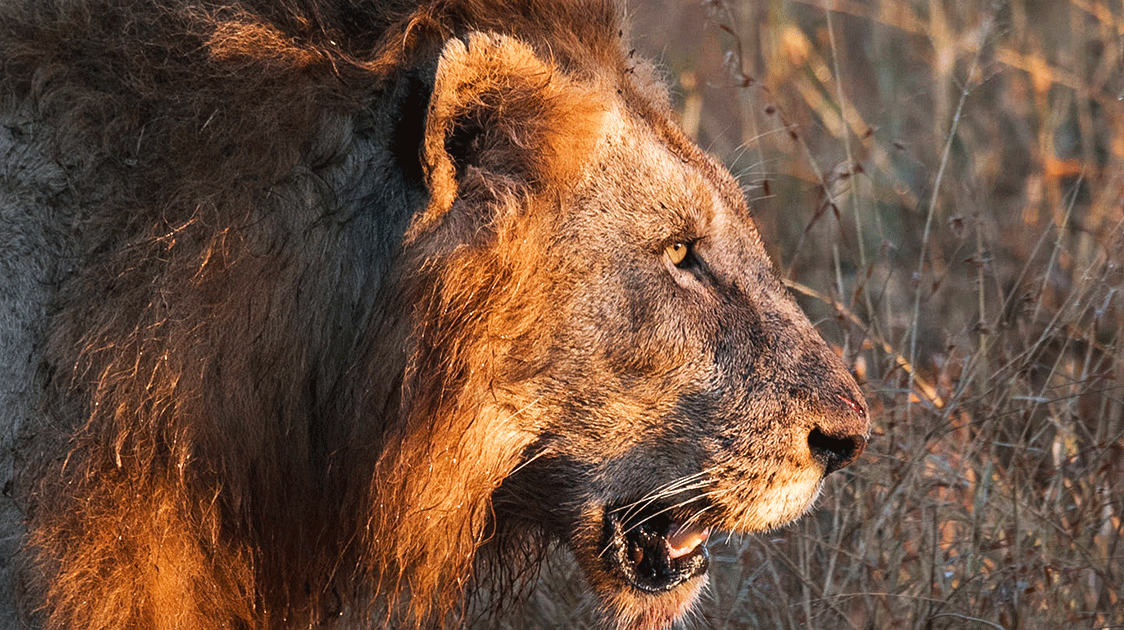

In northern Kenya, the far north has already experienced severe desertification under cattle pastoralism, and camel pastoralism is the norm (Gabbra, Rendille and Turkana).

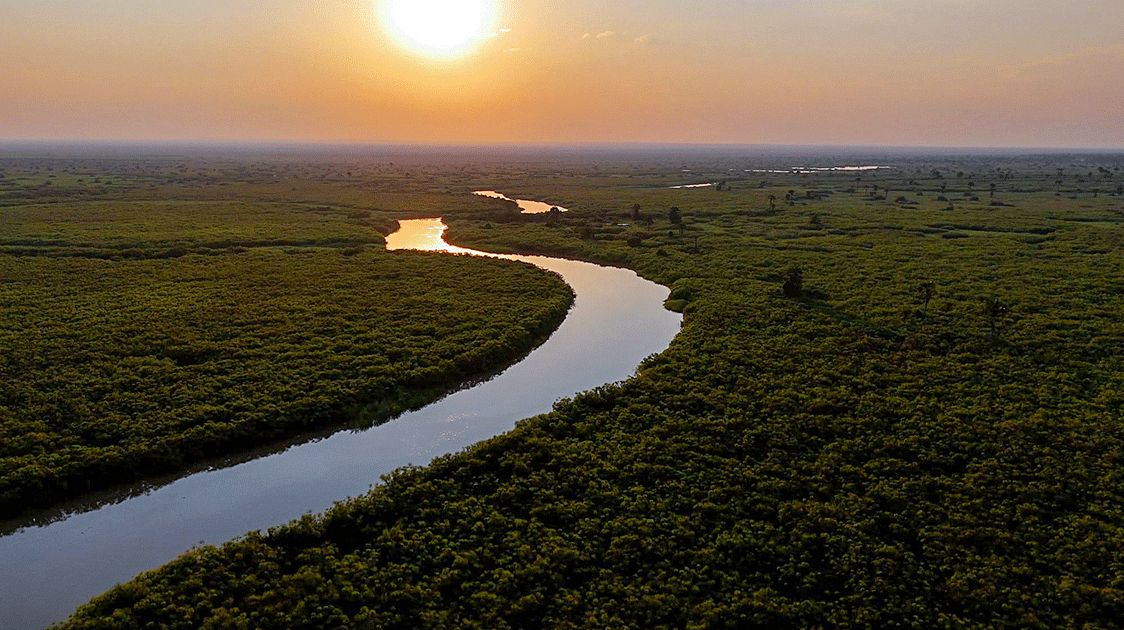

Further south, the lowland (aka lowveld) areas are still undergoing the transformation of land from biodiversity-rich to poor, with active deforestation, overgrazing and soil loss under cattle pastoralism.

My main argument has been, convert to camel pastoralism before the land has been completely degraded by cattle and small stock into Stage 3 of the Patrol 61 article.

This will maintain ground cover and prevent soil loss, which will maintain the land’s ability to regenerate vegetation when the rains return.

Repeated cycles of soil loss during dry periods under cattle pastoralism progressively diminishes vegetation regeneration, the very definition of desertification.

By all means, get rid of sheep, but keep some goats. Goats, like camels, feed from multiple vegetation types and spread out when browsing.

Their main disadvantage is sharp hooves, which break up the soil, but some small stock are essential to a pastoralist subsistence system. Their population numbers are usually controlled from use for meat, ceremonies and a medium of exchange, so offtake is high.

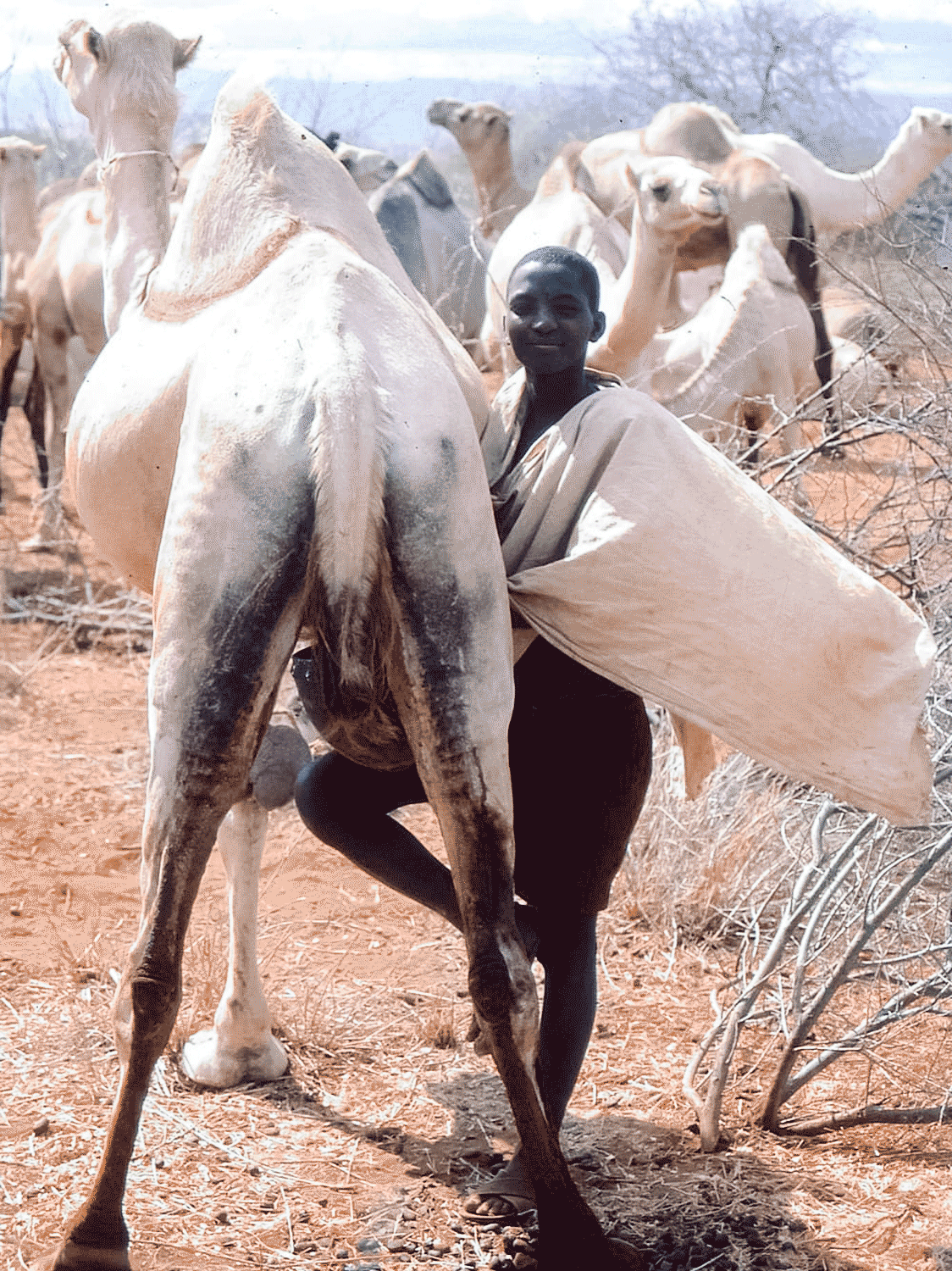

Camels are already being adopted by Samburu and Pokot cattle pastoralists in Kenya, but at a very slow rate because of three main factors: unfamiliarity with camel management practices, the high cost of camels, and low availability.

Camel owners are reluctant to sell camels, particularly milk-producing females.

Environmental advantages of camels

The Stage 3 description ‘The Irreversible Nature of Camel-Induced Desertification’ in Patrol 61 contained errors of fact and a lack of understanding of the advantages that camels have over other livestock under traditional management systems.

I have extensively described why camels do not degrade land in the same way that other livestock do; the details are too lengthy to include here, but can be found here.

Camels basically leave the land in the desertified state in which they find it when being introduced, although if there are still cattle and livestock present on the range, further degradation can take place.

Other important factors in hastening land degradation are human population growth and loss of grazing land from land alienation for other purposes, forcing more humans and livestock into smaller areas.

To summarize camel advantages that both reduce the need for numbers as high as other stock and why they are much less deleterious to the land:

- Camels produce much more milk on a more regular basis than other stock, even during drought periods, meaning fewer are needed for subsistence;

- Camels forage widely, from all stories of the vegetation, thus putting much less pressure on ground cover, which is the type that, when removed, leads to soil erosion. Tree and shrub leaves grow back;

- Camels do not have hooves, their foot pads are soft, so they do not break up the soil like other stock;

- Camels reproduce significantly more slowly than other stock. Ethnic groups with long experience with camels (eg. Gabbra) adapt to camel demographics and introduce many cultural practices that reduce the human growth rate.

Additional benefits of camels are that the milk is healthier than other milks, being higher in vitamin C and containing less fat, and not being ruminants, they produce significantly less methane, a harmful greenhouse gas.

I have not visited northern Kenya for many years, so I do not know what has been happening in terms of pastoralist economies.

Apparently there has been intensified camel milk production amongst the Somali and commercialization of the milk and meat, and camel numbers have increased from less than one million in 1990 to well over three million today, but if conversion to camel pastoralism has not been assisted by government policy and financial assistance to enable cattle people to adopt more camels, with training to facilitate good camel management, then I am not very optimistic about what the condition the land might be in now.

Dr Stiles started out in anthropology and archaeology, researching past and present natural resource use with hunter-gatherers and pastoralists, moving to the UN system working in desertification control. In 1999, he began investigating wildlife trade, producing reports and publications for UN agencies, the IUCN, TRAFFIC, and various NGOs.