When Authority Becomes Tyranny

By Prof Brian Child

In my early career working with African villages, I, like many others, assumed that these small communities had high levels of social capital. Surveys of livelihoods and governance in dryland communities in at least five countries in Southern Africa suggest the opposite.

Trust within communities is low, and confidence in leaders is low, especially with money. Associational capital is also weak, largely authoritarian, and top-down, with chiefs and churches predominating.

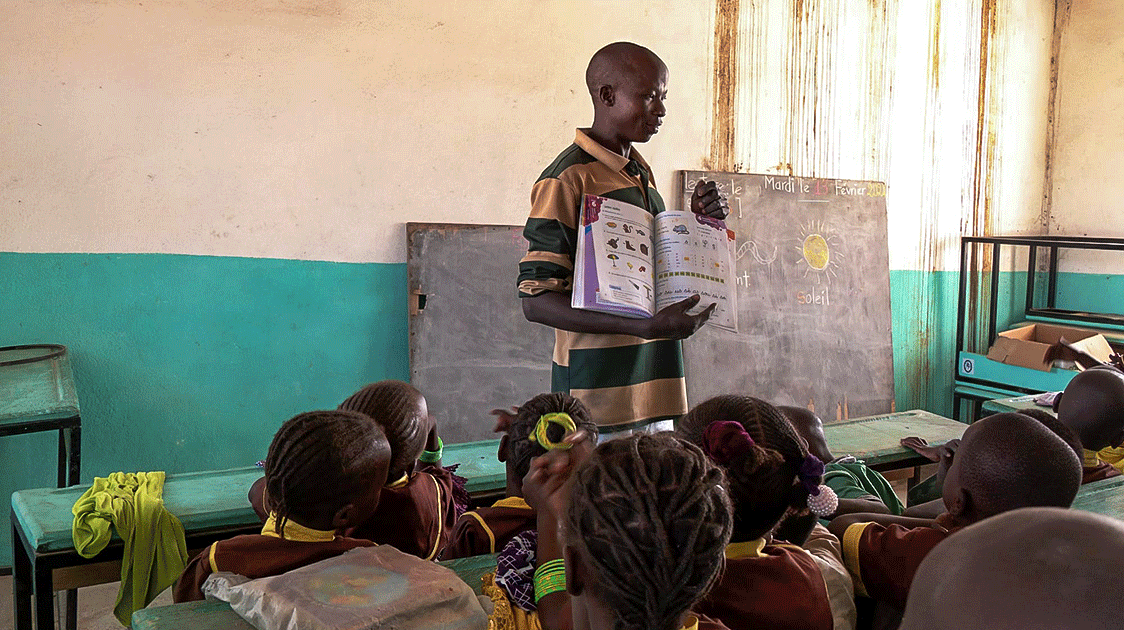

There is some engagement in cultural activities, schools, and burial societies, but communities seldom work together collectively in resource management or business.

Scattered settlement patterns also hint at an impulse to hide away from authority and even violence, forgoing the benefits of small-scale artisanal specialization and diversification and the provision of services associated with economic clustering.

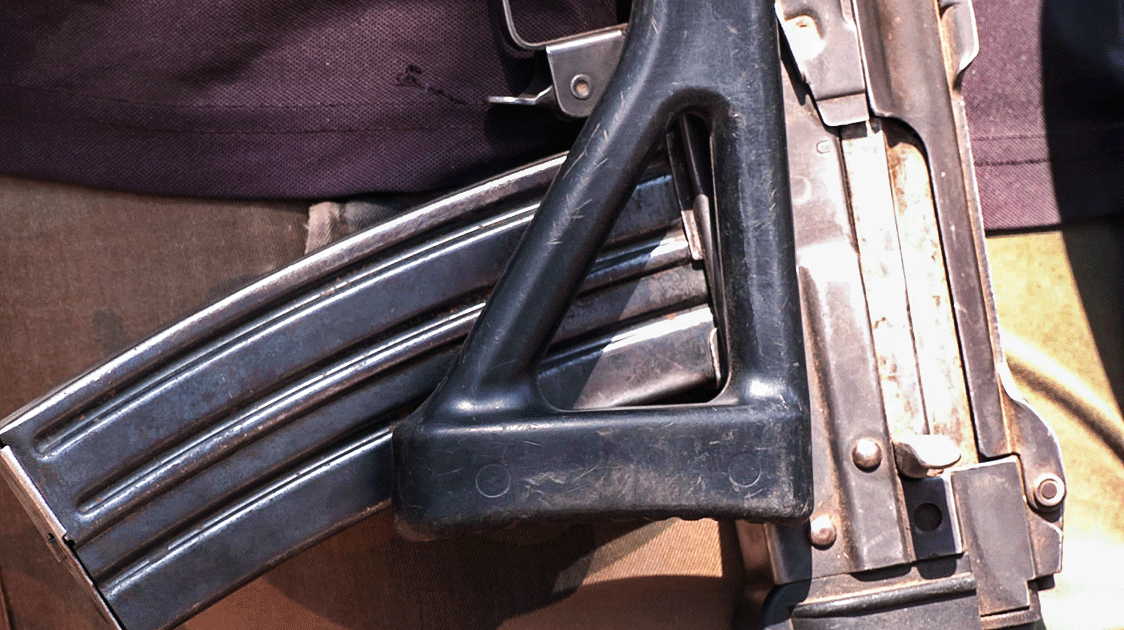

This suggests a further source of deinstitutionalization: severe social trauma and authoritarianism. Elites enriched and empowered themselves by selling people for muskets and trinkets in the inhumane slave trade, shattering communities that were also devastated by European diseases.

Conquest and colonialism destroyed the rights of local people, who were ruled indirectly, presumably often by the same elites that had gained so much from the slave trade.

The destruction of social systems in the colonial period was rarely corrected in the post-colonial period, where centralizing and authoritarian tendencies were exacerbated by the Cold War and enrichment opportunities.

A more benign example is the further centralization and politicization of the control of natural resources in Zambia, and community resources everywhere continue to be appropriated and looted.

Long histories of colonialism, racialism, and tribalism, and extractive governance models have left a legacy of divisiveness and powerlessness in which ordinary people are easily exploited by new elites with anti-democratic norms. We most often associate these features with troubled or failed states.

However, community leaders and leadership structures display the very same attributes of oppression and extraction, leading to what Musavengane and Simatele (2016) call ‘self-oppression’, where local people have lost faith in leadership, collective action, and themselves.

Freedom, the philosopher John Locke argued, comes most seriously under threat when those in authority use their power to attack the property of their own citizens, increasing their own riches and power by taking what they want from the people.

By property, Locke did not just mean rights to land, but rights to ‘Lives, Liberties and Estates’.

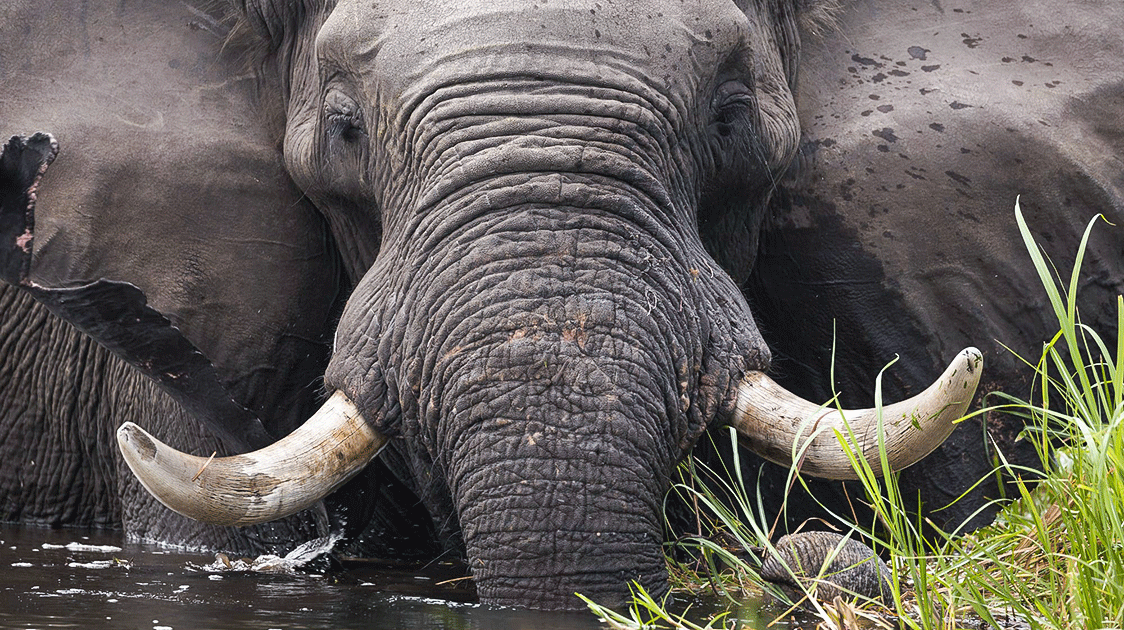

Just as we have prospered as Locke’s freedoms and rights have been normalized in some societies, so has the opposite happened in many rural communities, which are denied the rights to the land they live on and the wild resources they live with.

These rights, to this day, continue to be taken away. We can and should point accusatory fingers at state capture and resource extraction mechanisms that personally enrich Big Men and their cronies.

However, conservationists are also guilty when we disenfranchise local people with the best intentions in forums such as CITES, where decisions on local resources are often made without a single local person in the room.

The Wildlife Tragedy

The shining example of effective conservation is Roosevelt’s top-down ‘North American Model’, which has resulted in wonderful national parks and much more wildlife than a hundred years ago.

In a country built around capitalism, ironically, public management and central planning (perhaps even a socialist model) provide citizens considerable benefits, including cheap hunting and outdoor recreation access.

In terms of the alignment of property characteristics, rights, and ownership, the North American Model is somewhat misaligned, but it is held together by professional wildlife agencies, reliable funding mechanisms such as the Roberson-Pitman Act, federal and state budgets, numerous democratic checks and balances provided by civil society of municipal, state, and federal agencies, and by the investments in over 500 universities with schools training wildlife and forest managers.

However, it is a mistake to project this model to places that lack similar levels of inclusive and accountable governance, reliable financing, and technical capacity in universities and state agencies.

Yet, this is precisely what we have done, especially outside protected areas, resulting in extensive biodiversity losses through over-exploitation (bushmeat, illegal wildlife trade) and replacement (the cow and the plough).

The response to these dysfunctional systems is often dysfunctional, calling for more of the same, which is why we must challenge the underlying assumptions of current approaches.

For example, responses to the wildlife crises are invariably emotional thinking in ways that are ‘fast’, unconscious, automatic, and error-prone.

Perhaps recalling Teddy Roosevelt’s abhorrence of market hunting over one hundred years ago, the response to the illegal wildlife trade has not challenged the assumptions that markets are bad or that public management is good.

The fixation with demand reduction (despite the failure of this approach) and the trend for ever more centralization at the global level (rather than localization) has established a vicious circle whereby centralized conservation models vulnerable to democratic failure are reinforced by special interests that benefit from the status quo.

In some instances, this gets truly bizarre, depicting local people as anti-conservation, with only outsiders being good enough to take on this responsibility.

We have gone too far and must turn away from uncritical ideology and special interests towards a pragmatic, thoughtful search for the greatest good for the greatest number.

Solving multiple threats in complex social-ecological systems, like rocket-building, will not emerge from good intentions.

It requires pragmatic, considered, and tenacious application, as well as thinking slowly to understand whole systems.

(Prof Brian Child is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida and the Life Through Wildlife Project director. His book, “Sustainable Governance of Wildlife and Community-Based Natural Resource Management”, is available on Amazon.)