The $200 Poacher vs. The $50,000 Safari Hunter: Economics of Conservation

Key Takeaways:

- Wildlife in the savannas of Northern Cameroon is being decimated.

- The region is facing a myriad of threats from pastoralists to poachers.

- Hunting concessions comprise about 70% of the massive Bénoué Complex (23,394 km² in extent).

- The financial burden of protecting wildlife falls almost entirely on hunting companies.

- Small-time operators have been forced out because anti-poaching operations are no longer affordable.

- This has placed incredible pressure on the remaining operators.

- They are the last line of defense.

The Vanishing Wilderness

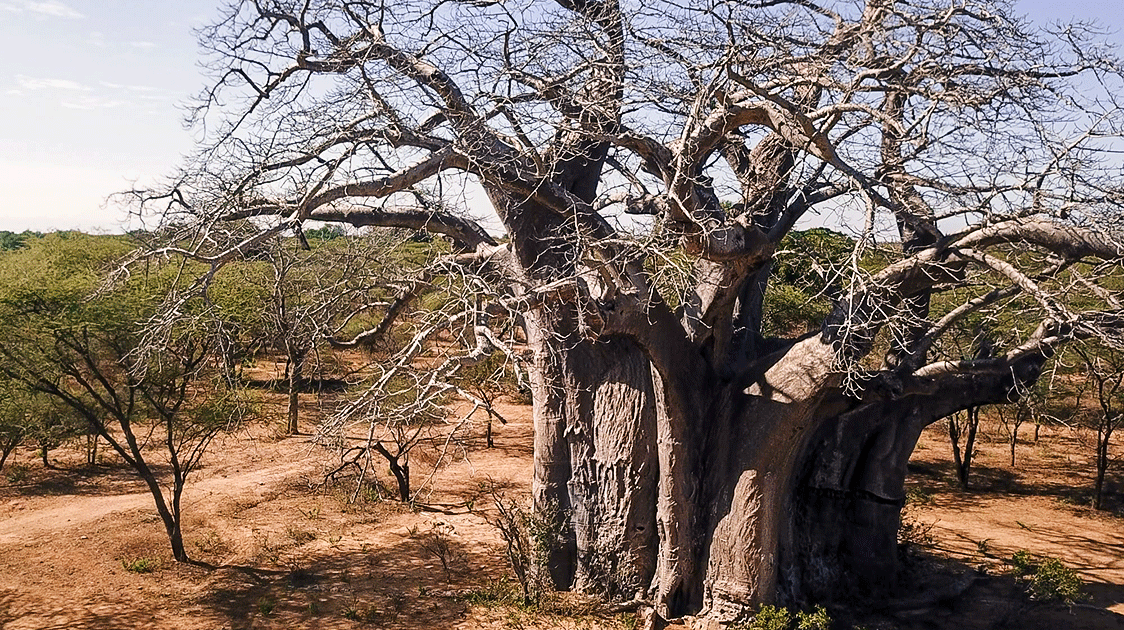

In Northern Cameroon's vast savanna woodlands, professional hunter Guav Johnson has witnessed one of Africa's most desperate conservation battles. As a veteran guide who first arrived at his camp in 2002, Johnson has watched the region transform from wildlife-rich into a landscape under siege.

His testimony reveals a harsh reality: hunting companies have become the unexpected last line of defense for some of Africa's most endangered species.

The story of Northern Cameroon's wildlife is one of gut-wrenching decline. Saudi, a former camp manager of half-Lebanese, half-French descent who was born in the city of Garoua in Northern Cameroon, once told Johnson how his father would walk from their house in town to hunt roan antelope and buffalo for meat, carrying it back home on foot.

"That's how much game there was," Johnson recalls. Today, one would need to drive at least seven hours from Garoua before encountering even a rabbit. "There's absolutely nothing. It's a desert."

A Unique Conservation Challenge

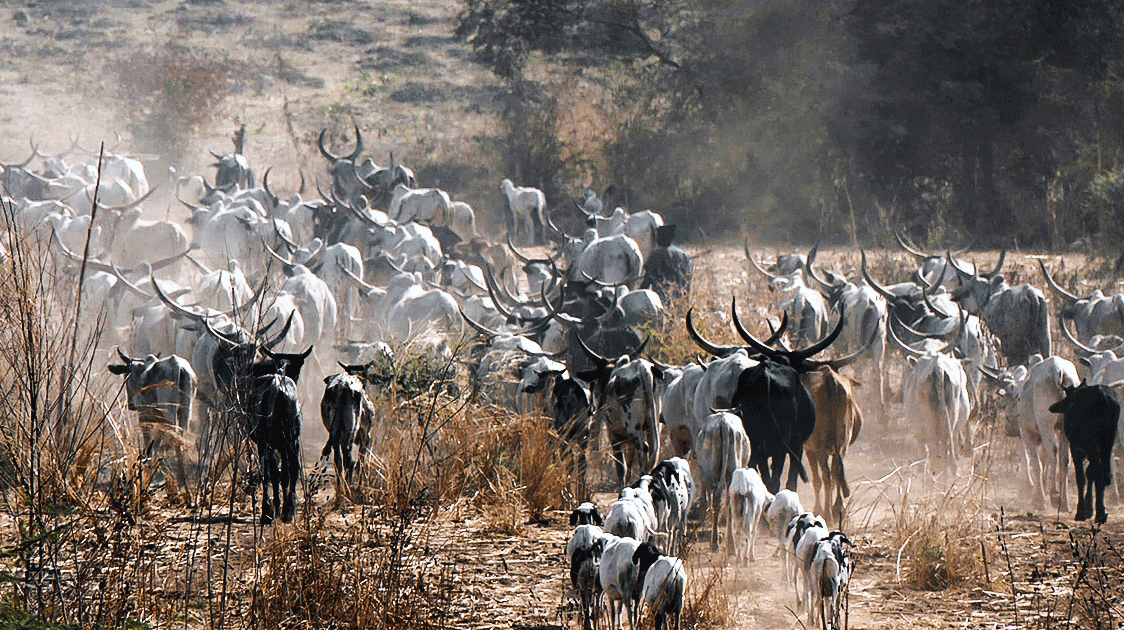

Northern Cameroon faces multiple key threats, including transhumance, the nomadic movement of ethnic groups with thousands of cattle across seasonal patterns and national borders, and the incursion of parks and hunting concessions by pastoralists.

These illegal livestock incursions are associated with competition for grazing, persecution of predators, elevated poaching, and the destruction of trees to provide fodder.

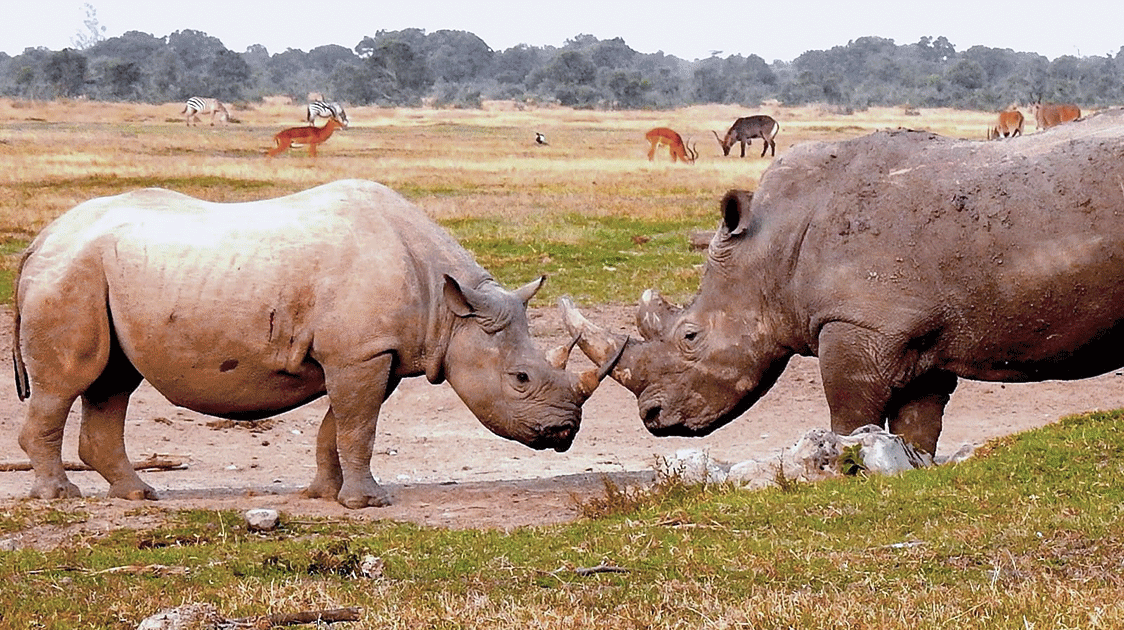

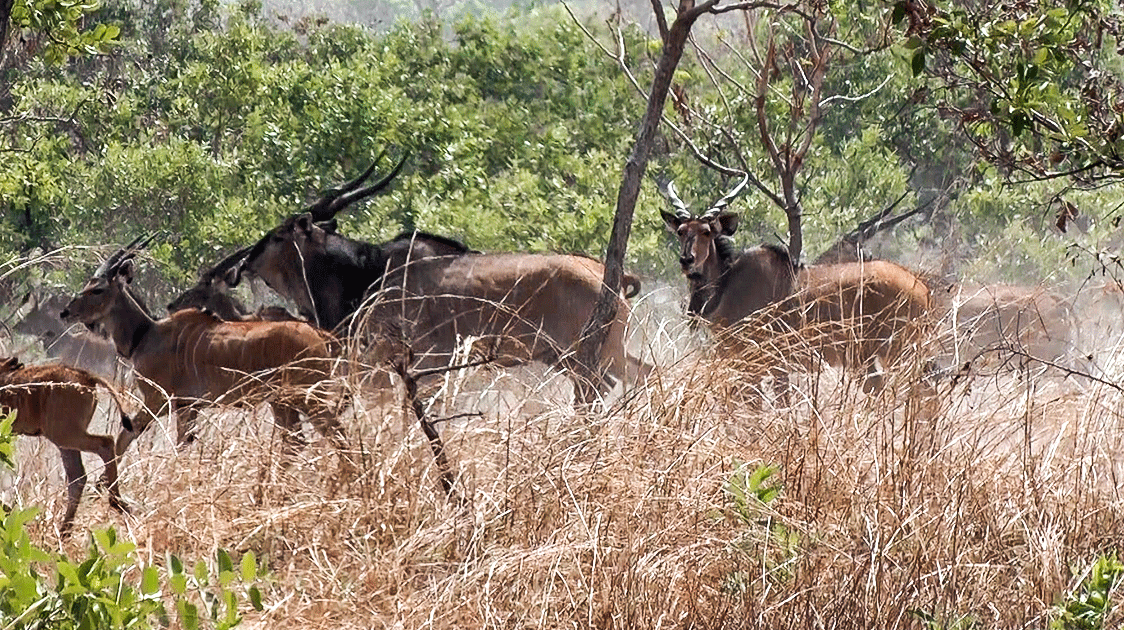

The region's wildlife includes species found in very few locations. The giant eland (Lord Derby's eland) occurs in only a handful of countries, with Cameroon being the only one where they remain huntable; other populations exist only in conflict zones.

The IUCN lists Eastern giant elands as vulnerable, while Western giant elands are classified as critically endangered.

The massive Bénoué Complex (23,394 km²), comprising three national parks (Bénoué, Bouba Ndjida, and Faro, combined 7,580 km²) and surrounding hunting zones, is a key conservation area for lions in the Central African region.

Hunting concessions comprise about 70% of the protected area. Recent estimates suggest Bouba Njida has around 80 lions, with a national population of approximately 270 individuals, with the largest populations in the Faro and Bouba Njida ecosystems.

The Evolution of the Poaching Crisis

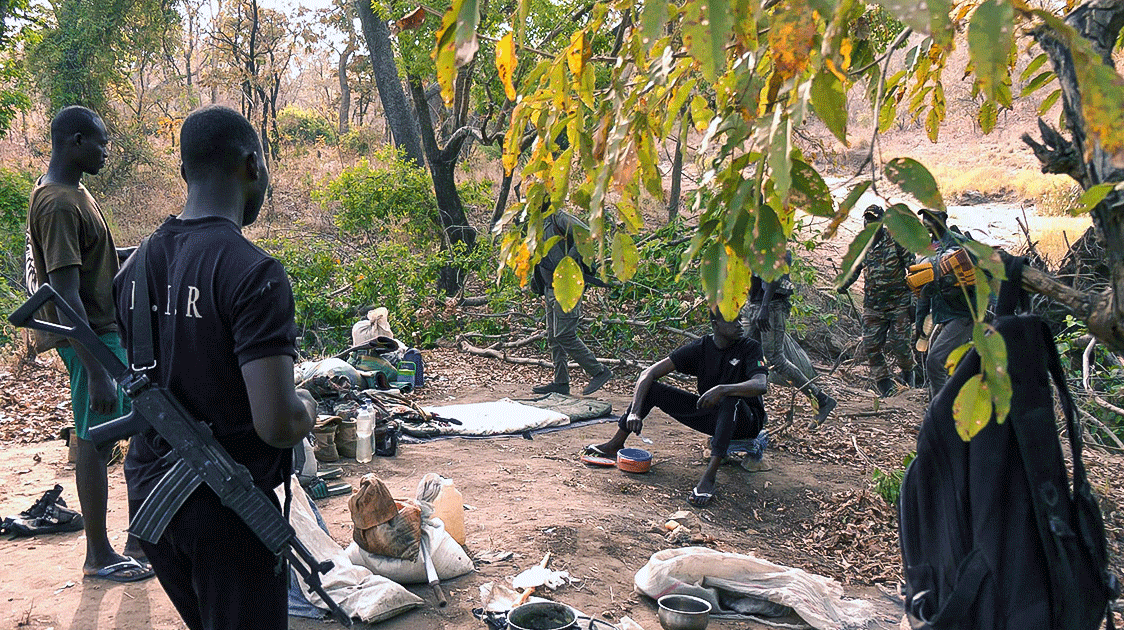

When Johnson first started hunting in the region, poaching wasn't considered a significant threat. Game scouts, unarmed teams of six to eight men carrying only machetes and axes, patrolled under the supervision of professional hunters.

However, the situation deteriorated rapidly. As poachers became increasingly armed, hunting companies were forced to hire military personnel to accompany their scouts.

"You can't expect game scouts carrying machetes to arrest gangs of armed poachers," Johnson explains. The company now employs over a hundred people, making it probably the biggest employer in the region.

The methods of poaching have evolved into a sophisticated operation. Cable snares made from motorcycle clutch or brake cables are the most common method, with poachers digging holes and attaching nooses to heavy logs.

Homemade shotguns are used for night hunting, wounding and killing many animals. Poachers even poison water holes with cotton pesticides, killing anything that drinks there: birds, animals, whatever comes.

The economic disparity is stark. A poacher who kills a giant eland and processes the meat might earn less than $200 from the sale, while a legal hunting client pays $40,000 to $50,000 for the same animal, money that creates jobs and funds conservation efforts.

The Communication Revolution and Its Consequences

The arrival of cell phone service around 2014 transformed the poaching landscape. Previously, for those who could afford it, Northern Cameroon relied solely on satellite phones for communication.

Now, with widespread cell coverage, poachers can coordinate their operations with unprecedented efficiency. They shoot animals, skin them, cut up the meat, and smoke it on racks over fires to cure it.

Once they have enough dried meat, they use cell phones to call in motorcycles for transport to markets in towns like Garoua, the second-largest city in northern Cameroon, about 150 kilometers away.

The main weak point for conservation is a public road running through the center of many concession areas. "It's very easy for poachers to come in and carry meat out, and there's no one to control the movement on that road," Johnson notes.

The Transhumance Crisis

Beyond poaching, the second biggest challenge comes from nomadic cattle herders. Transhumance is a common practice for pastoralists and their cattle herds to cope with the ecological and environmental constraints of the dry season.

These seasonal livestock migrations can generate conflicts between pastoralists and local farming communities over limited natural resources and damage to crops.

These nomadic groups, including the Indigenous Mbororo Peoples, move their herds freely between the Central African Republic, Nigeria, Chad, and Cameroon.

Conflicts between nomads and farmers, cattle rustling, and lack of security in non-demarcated protected areas have resulted in thousands of deaths over the past two decades.

The herders often see predators like lions as threats and kill them wherever possible. Their livestock compete with wildlife for forage and water, creating additional pressure on already stressed ecosystems.

The COVID-19 Catastrophe

When the pandemic struck and lockdowns began, tourism disappeared virtually overnight, taking with it the dollars that parks and surrounding communities depend on.

The absence of foreign visitors significantly impacted security; without extra eyes and ears on the ground, poachers could enter parks without worrying about encountering safari operators and guests.

Johnson describes COVID-19's impact as devastating. The entire 2020 season was cancelled, leaving no income to pay anti-poaching personnel.

"I think the very worst two years of poaching that we ever had were from the start of COVID, going two years in," he recalls. Travel restrictions initially reduced poaching, but once lifted, traffickers found their way back to the illegal trade, with demand for ivory remaining high, especially in Asian countries.

The pandemic's impact was complex, as some urban areas saw reduced bushmeat consumption due to fears about COVID-19's links to wildlife. Meanwhile, rural communities increasingly turned to bushmeat as COVID-related restrictions led to job losses, declining incomes, and rising food costs.

The Economics of Conservation

The financial burden of protecting wildlife falls almost entirely on hunting companies. With money raised through trophy fees, hunting companies can afford to run anti-poaching units with permanent 24/7 patrols.

Each concession typically deploys scouts for five-day to week-long patrols in the most threatened areas, always those closest to villages, despite distances of 20-30 kilometers.

Several small-time operators with single concessions have been forced to abandon their areas because they could no longer afford the anti-poaching efforts required to make the concessions viable.

Johnson observes, "We're now in a situation where our neighbors have left and there's no protection there. We basically border on a concession that has no control at all."

Mayo Oldiri, the hunting company that Guav works for, has established relationships with communities by providing employment (often hiring former poachers for anti-poaching teams), medicine, school materials, and free meat from hunted animals.

This helps communities understand that legal safari hunting offers significantly more benefits than poaching.

A Vision for Solutions

Johnson and other conservationists have identified several potential solutions. The use of microlight aircraft or savanna aircraft would revolutionize anti-poaching efforts.

"Without roads, it would take days, if not weeks, sometimes to locate camps. With a small aircraft like that, in an hour you would've covered the whole concession."

However, Cameroon's strict regulations regarding military-like equipment and aircraft create bureaucratic hurdles. The solution might be working with national parks to import and operate such equipment under their authority.

Johnson also suggests that organizations like African Parks could take over abandoned hunting blocks, managing security and anti-poaching while allowing hunting operators to continue their work, paying concession fees and employing local communities. "That could be the answer so that everyone is happy."

The recent deployment of Cameroon's military forces to assist rangers represents a significant escalation in anti-poaching efforts.

Mixed patrols of military and civilian rangers now frequently arrest foreign and Cameroonian poachers, cattle herders, and artisanal gold miners.

However, this militarization of conservation has fueled local resentment in some areas.

Community Engagement: A Critical Component

Alternative livelihood programs in other parts of Cameroon have shown promise. A three-year project near Dja Faunal Reserve, one of Africa's largest rainforests, demonstrated that providing farming support, technical expertise for cacao farms, and fishing development successfully reduced hunting behavior. Participants spent more time on farms and less time in the forest poaching.

The Ticking Clock

The situation has reached a critical juncture. Johnson's assessment is sobering: "We are not at a point yet where it's not salvageable. We can still make a plan and get these numbers of these animals back up." But time is running out. Without drastic changes, he warns, "we will end up losing all of these areas. The pressure is too much."

Conclusion: The Last Stand

The hunting companies of Northern Cameroon have become the bulwark against the complete collapse of the region's wildlife. They fund anti-poaching patrols, employ local communities, and maintain vast areas that poachers and cattle would otherwise overrun.

Johnson's final words carry the weight of someone who has watched paradise disappear: "The hunting companies in Northern Cameroon are the last line of defense for these animals. You could go into a hunting area right now, see what game they have, and then go into a hunting area where the operator has pulled out due to a lack of funds for proper anti-poaching efforts. Those areas are annihilated. There's nothing there; it's full of poachers, cattle, and domestic livestock. It's finished."

The story of Northern Cameroon is not unique in Africa. It represents a microcosm of the continent's conservation challenges.

It's a story where traditional fortress conservation models have failed, where poverty drives ecological destruction, and where the future of iconic species hangs in the balance.

Whether this last line of defense can hold, or whether new models of conservation can emerge in time, will determine not just the fate of the giant eland and other species, but the entire ecological heritage of Central Africa.