The Chete Safari Area: A Forsaken Wilderness

With Dick Fourie

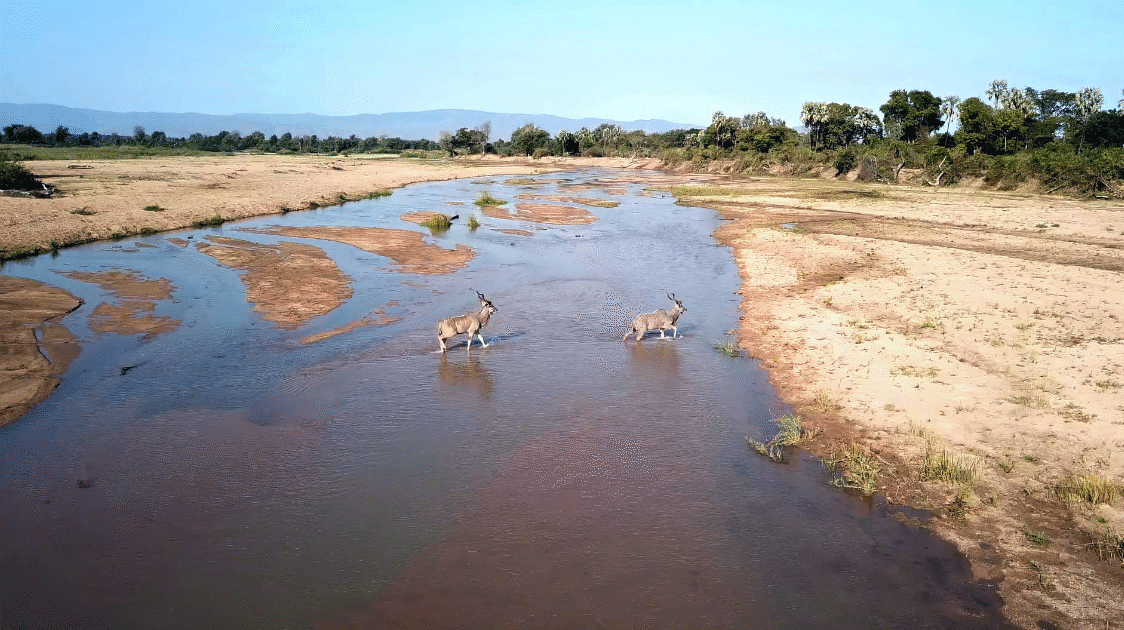

The Chete Safari Area is a vast, rugged, undeveloped wilderness on the Zimbabwean shoreline of Lake Kariba. Covering 108,100 hectares between the Senkwe and Muenda rivers, it forms part of the lower Zambezi–Kariba ecosystem.

It occupies a critical ecological position within a broader mosaic of protected areas stretching along the Zambezi Valley.

Chete is remarkable for its biodiversity. It resembles a cross-section of Zimbabwe's major biospheres, moving from miombo woodland reminiscent of the central plateau, through dense jesse bush typical of the Sapi, Chewore, and Dande areas, into mature riverine forests like those found along the upper Zambezi.

This is sharply contrasted by harsh mopane scrub, broken escarpments, and deep gorges, landscapes more commonly associated with Makuti and Chizarira.

Numerous natural springs are scattered throughout the concession, ensuring a constant water supply and supporting a variety of wildlife.

The area plays a strategic role in regional connectivity, supporting elephant movement, large predators, plains game species, and significant waterbird populations along the lake and river systems.

It is designated as a controlled safari hunting area and has historically been managed within Zimbabwe's broader Zambezi Valley conservation framework.

Historical Context and Decline

Chete's formal conservation history dates back to the colonial era, when the territory was incorporated into the state's reserved lands system.

Like many of Zimbabwe's national parks and safari areas, it was formally gazetted in the mid-20th century and later consolidated under the authority of the Parks and Wildlife Management structures that emerged towards the 1970s.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, regional initiatives aimed at tsetse fly eradication and disease control prompted limited infrastructure development, including the establishment of access routes into parts of Chete and surrounding state land.

These efforts were never extensive, and the area remained isolated, with only a minimal road network penetrating its interior.

For decades, Chete generated revenue through regulated safari hunting, providing some employment opportunities while maintaining relatively low ecological disturbance due to its remoteness.

However, this same isolation also limited diversification into photographic tourism and broader economic activity.

The situation deteriorated significantly during Zimbabwe's economic and institutional crisis of the early 2000s.

As with many protected areas across the country, law enforcement capacity declined, infrastructure was neglected, and poaching pressure escalated. Chete, difficult to access and inadequately resourced, became increasingly vulnerable.

Contemporary Conservation Efforts

Despite these challenges, individual conservationists have continued to invest time, resources, and personal commitment into protecting the area.

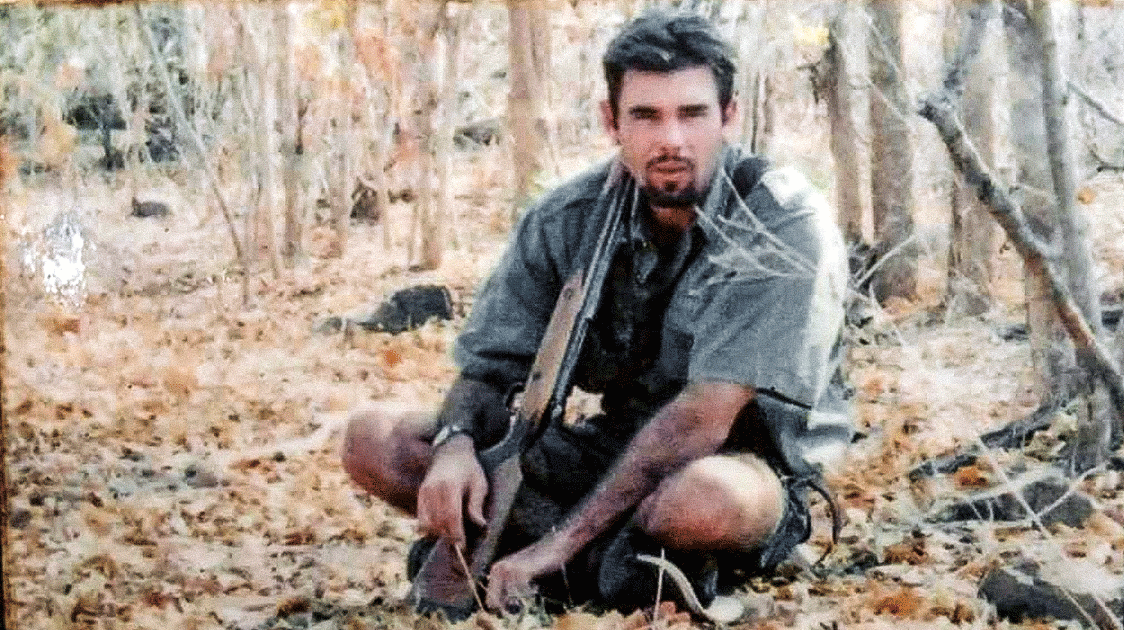

One such figure is Dick Fourie, whose life has been closely tied to Lake Kariba and the surrounding Zambezi Valley.

Having spent much of his upbringing between Lake Kariba, Sengwa, and Sinamwenda, Fourie developed an early familiarity with the region.

His formative years were shaped by managing kapenta fishing operations on the lake during school holidays.

His professional career later included work with safari operators in the Zambezi Valley, qualification as a professional hunter in 2005, and senior management roles in Chete and neighbouring safari areas between 2008 and 2012.

Inspired by Edmund Burke's maxim that "all that is needed for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing," Fourie has committed himself to conservation work in Chete.

He began conducting regular anti-poaching patrols in coordination with Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZimParks) scouts.

Typically operating at least once a month, these patrols focus on both terrestrial incursions and lake-based poaching activity.

Working relationships with ZimParks personnel have been instrumental, allowing limited civilian resources to supplement official enforcement.

These operations are funded modestly by Fourie himself and a handful of fishing friends who sometimes accompany him on expeditions.

His resources are limited to a boat, a vehicle, enough cash for fuel and oil and most of all, his time.

To improve effectiveness, he notes that more boats, fuel, and radios, along with additional volunteers with free time, would be invaluable.

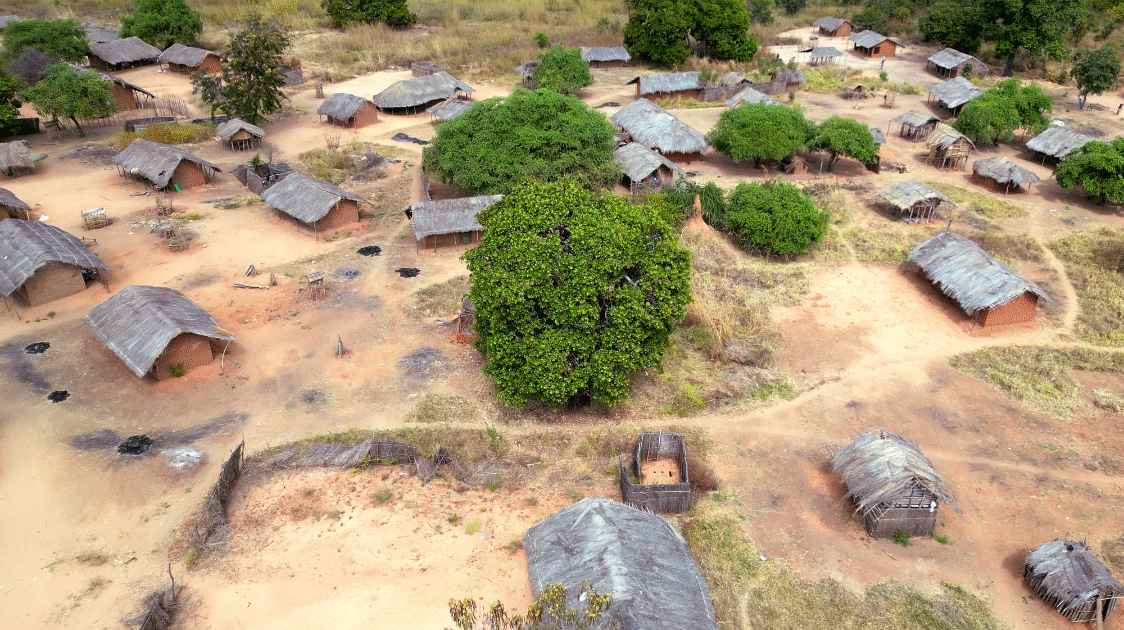

Equally important has been strong engagement with local traditional leadership.

Long-standing personal ties to the region, combined with economic relationships built over many years, have fostered trust that supports conservation efforts in an otherwise fragile socio-economic landscape.

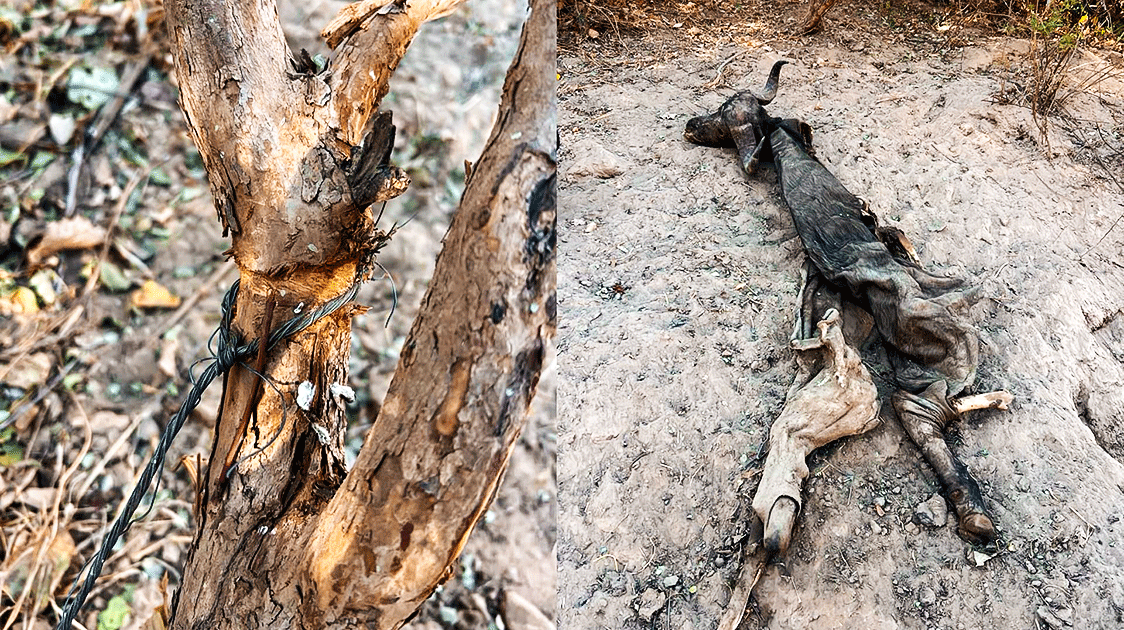

Poaching Patterns in Chete

The Chete Safari Area's geography provides some natural protection: an escarpment forms its southern boundary, forcing poachers to travel considerable distances to reach it.

The typical poaching gang consists of a four-man crew accompanied by 10 to 30 dogs, a relatively new pattern in Chete, where the use of dogs was previously unheard of.

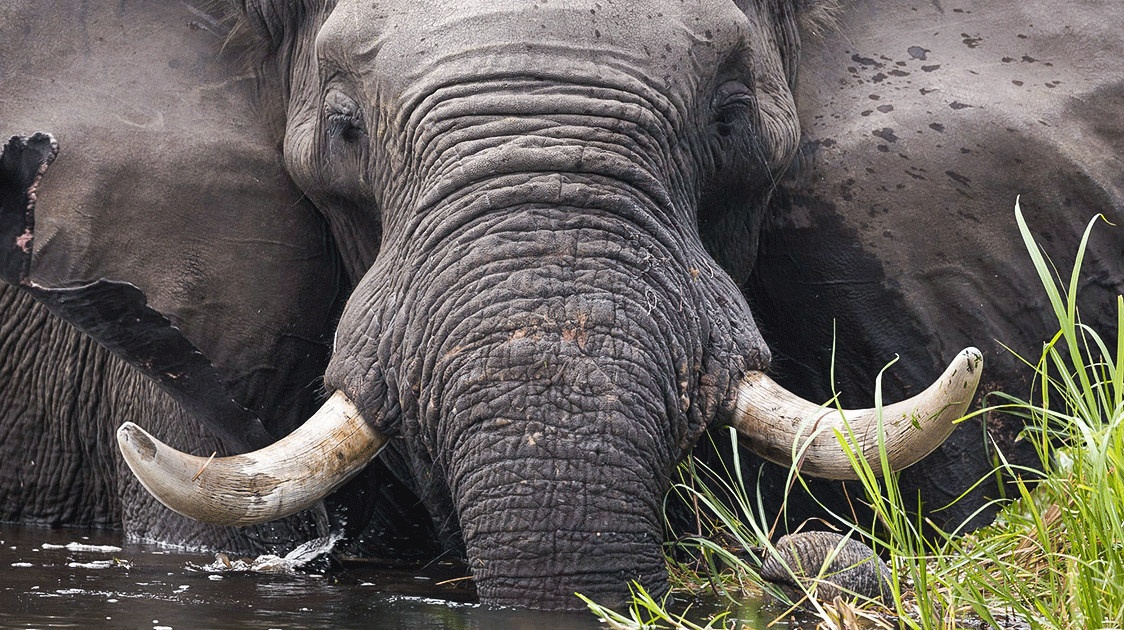

According to Fourie, plains game species are not the primary targets. Buffalo are far more economically attractive due to their size: a bull weighs between 650 and 900 kg, while cows range from 425 to 700 kg.

Although bulls yield more meat, poachers and their dogs find it easier to target cows and calves within herds.

Once killed, the meat is cut into strips and air-dried, losing approximately 45% of the animal's live weight.

A 500 kg cow yields roughly 275 kg of dried meat, which sells for USD 2–4 per kilogram. At the lower price, each of the four poachers earns around USD 130 per buffalo, a significant return in an impoverished region.

The combination of profitability, limited enforcement efficacy and entrenched poverty continues to drive wildlife crime.

Lake Kariba and Cross-Border Fish Poaching

Equally severe is organized fish poaching along the Chete shoreline of Lake Kariba.

These operations are typically run by Zambian syndicates collaborating with Zimbabwean nationals.

Professional Hunter Pete Fick talks about an anti-poaching patrol up the Ruzi River

Under the cover of darkness, fresh supplies and nets are smuggled across the lake by canoe from Zambia, while smoked fish is transported back to Zambian villages for sale.

When a Zimbabwean poacher is arrested, the syndicate replaces him within days, ensuring uninterrupted operations.

Both Zambian and Zimbabwean kapenta fishing rigs have become integrated into this criminal economy, providing cover, transport and logistical support.

Tiger fish enter the river systems that feed into Lake Kariba to breed. Fish poachers are killing these fish indiscriminately

On any given day, kapenta rigs can be seen moored along the Chete mainland shoreline, their crews helping themselves to firewood, establishing temporary bases, and collaborating with inland poachers.

A disturbing recent development is the poisoning of river pools to harvest fish, a practice that kills indiscriminately and contaminates entire aquatic systems.

Operational Challenges

The Chete Safari Area's remoteness compounds the difficulty of conservation work.

The internal road network is virtually non-existent, making boat access the most practical option, though lake and river patrols are time-consuming and expensive.

The nearest town on the lake shore is Binga, 55 kilometers away, where petrol costs USD 1.65 per liter, outboard motor oil costs USD 30 per liter, and a 100-hour motor service costs USD 950.

Boat Running Costs Per Hour

|

Item |

Cost (USD) |

|

Fuel (18 liters × USD 1.65) |

29.70 |

|

Oil (0.5 liters × USD 30) |

15.00 |

|

Motor Service (USD 950 ÷ 100 hrs) |

9.50 |

|

Total per hour |

54.20 |

A typical day patrol involves approximately 5 hours of boat operation and costs around USD 270 in total.

These patrols include a ZimParks ranger, and a successful operation may result in the apprehension of six poachers along with 20 kg of fish each and their gill nets.

A fish poacher runs away from an anti-poaching patrol leaving his canoe, fishing nets, fish and supplies behind

The legal framework presents its own challenges. A poacher can only be detained for 24 hours before being handed over to the police for processing.

Fish poachers typically receive fines and are released within days.

Meat poachers, by contrast, face a minimum of 10 months in prison, a disparity that does little to deter the organized syndicates targeting Lake Kariba's fisheries.

An Uncertain Future

The Chete Safari Area remains a place of immense ecological significance and stark conservation vulnerability.

Its remoteness has preserved its wilderness character but also constrained effective management and economic resilience.

Current protection depends heavily on an underfunded state agency and the personal commitment of a small number of individuals willing to absorb financial and physical risk.

Meaningful improvement will require additional boats, fuel, communication equipment and, above all, committed personnel with time to dedicate to sustained patrol effort.

Without this, Chete risks continuing along a trajectory of slow attrition, where wildlife losses quietly accumulate out of sight of the outside world.

In many ways, Chete stands as a microcosm of conservation in remote parts of Africa, rich in natural capital but chronically short of the resources required to protect it.