The Canary in the Coal Mine?

By Zig Mackintosh

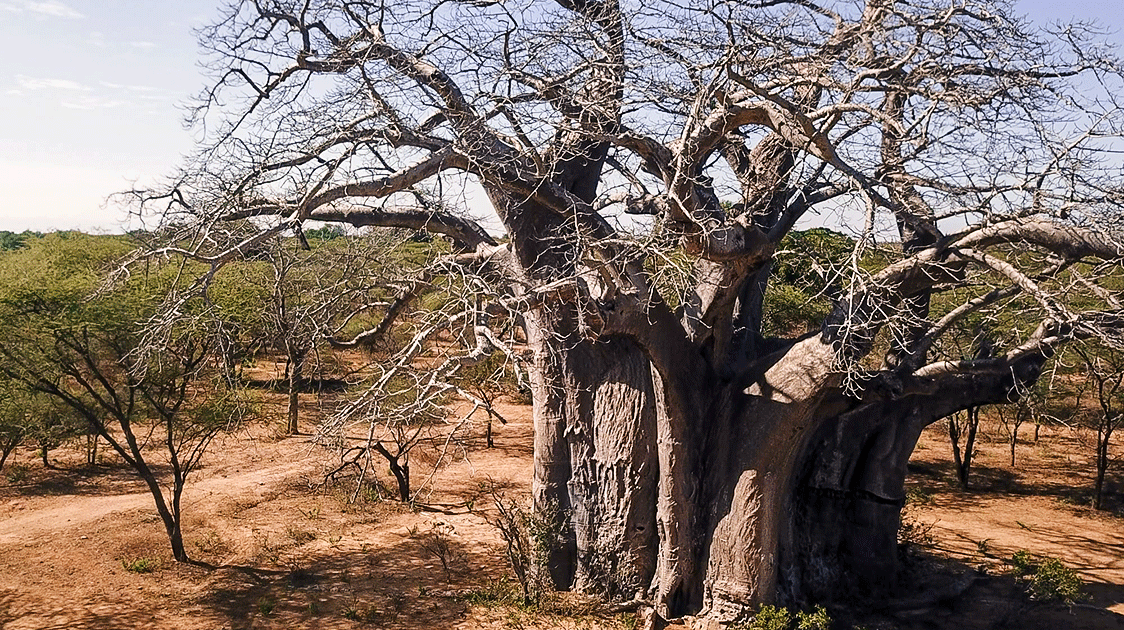

The baobab (Adansonia digitata) is tough and can live between 1,500 and 2,000 years. The species has evolved over thousands of years alongside elephants, climate extremes, and fire. When they start to die at scale, something’s up.

Baobab decline matters.

It is not about losing a charismatic species.

It’s the eeriness of an alarm signal that’s being ignored.

Tsavo, a documented warning from the past

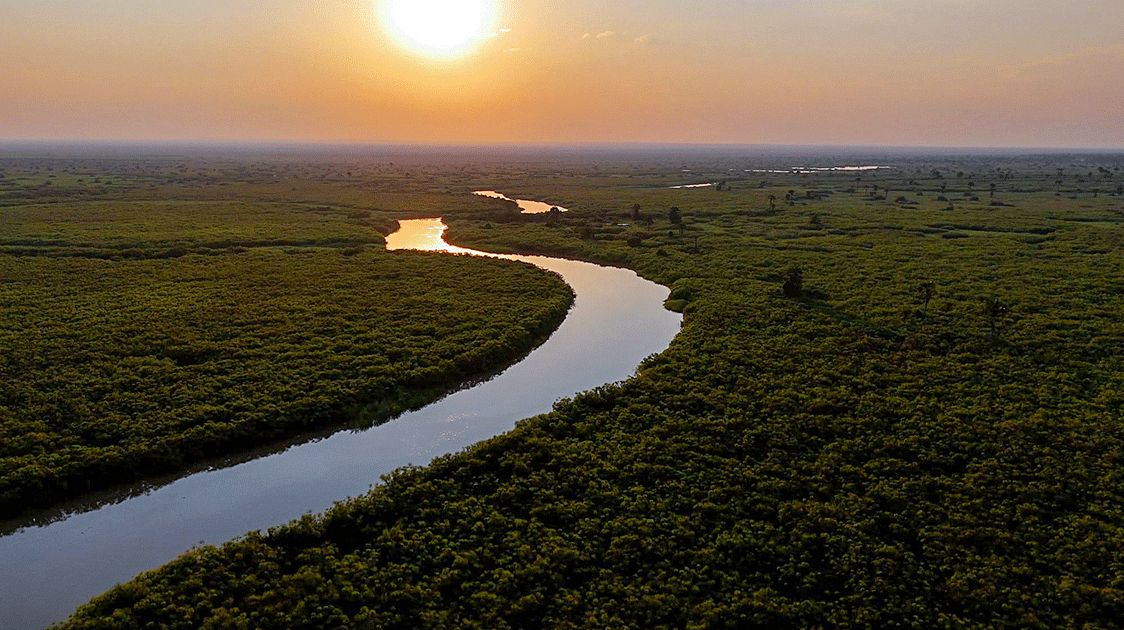

When Tsavo National Park was established in 1948, it supported extensive woodland, including baobabs.

An aerial census conducted in 1962 estimated the elephant population at around 10,800 (Glover, 1963).

By 1967, it was 35,000 (Laws, 1969), the largest concentration in the world.

This massive increase was due to an exploding human population and corresponding agricultural expansion outside the park, which compressed elephant ranges, forcing thousands of elephants into the sanctuary.

Demands for an elephant cull to save the park’s vegetation from destruction were dismissed by the park’s chief warden, David Sheldrick.

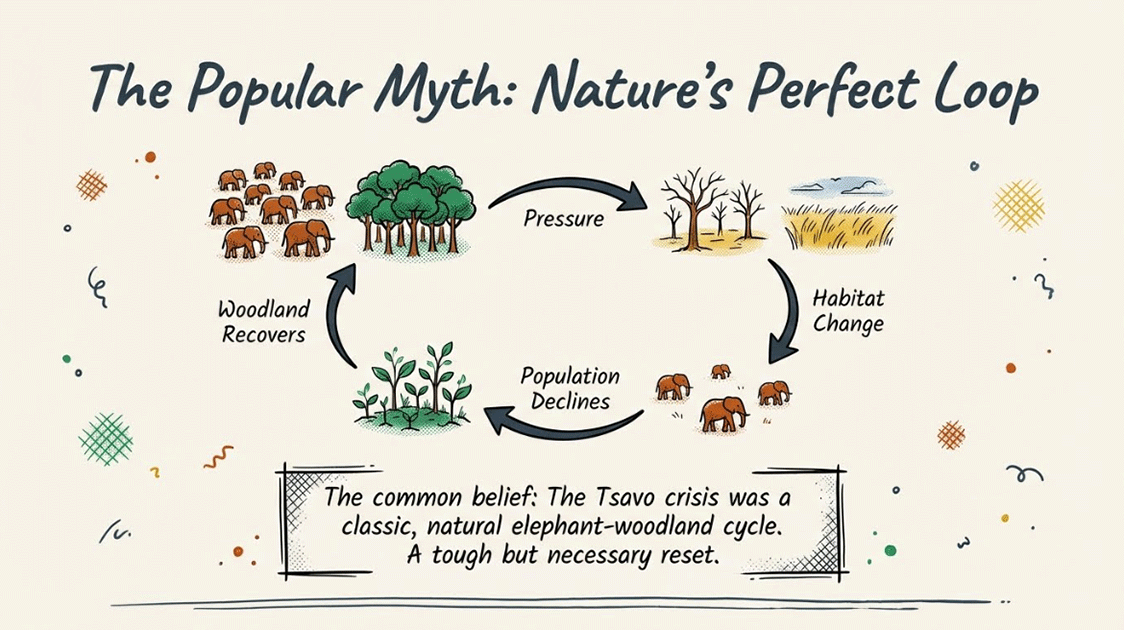

He believed the situation would self-correct through a “natural cycle”.

Elephants destroy woodland → grassland expands → elephant carrying capacity declines → elephant population falls → woodland recovers → cycle repeats.

But there is a fundamental flaw in this thinking that Sheldrick must have known.

The elephant population of Tsavo didn’t decline in response to vegetation degradation.

The park’s artificial water sources sustained them and encouraged continued immigration from surrounding areas.

In a truly natural system, elephants would disperse during periods of vegetation stress.

At Tsavo, they couldn’t.

The “cycle” proponents essentially argue that a system under artificial constraints will behave as if unconstrained, which is ecologically incoherent.

It was a severe drought in 1971 that killed at least 7,000 elephants, followed by an ivory poaching spree (sponsored by the wife of the president) that reduced the population to 6,000 and gave the vegetation a chance to recover.

The only “self-correction” that occurred was anthropogenic (poaching), not a natural feedback mechanism that would reliably restore woodland.

Documenting the damage

Walter Leuthold’s work on vegetation change in Tsavo East National Park is one of the clearest records.

By the mid-1970s, he reported that baobabs had become rare or virtually absent in surveyed areas, following intense elephant damage and drought stress (Leuthold, 1977).

When elephants cannot move freely in response to habitat conditions and seasonal rainfall, they concentrate, leading to the collapse of long-lived tree species.

Once that collapse starts, recovery is measured in centuries, not years.

A widely cited scientific assessment of elephant impacts summarizes Tsavo as a textbook example of this process.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/elephant-management/effects-of-elephants-on-ecosystems-and-biodiversity/B3EF514DCBC64BE53E147A859FAD50F8

These impacts are amplified during droughts, when elephants rely more heavily on woody vegetation, including baobabs, stripping bark and repeatedly damaging trunks.

Today, around 17,000 elephants live in Tsavo, approaching the densities that caused the original destruction.

Tsavo yesterday is Kruger today

In Kruger National Park, the same symptoms observed in Tsavo decades ago are appearing:

- Elephants are structurally damaging adult trees.

- Mortality spikes during drought cycles.

- Young baobabs are rare or absent in heavily used elephant areas.

- The population is ageing, with few replacement trees coming through.

This pattern is consistent with what ecologists have documented elsewhere when browsing pressure exceeds the regenerative capacity of woody vegetation.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01311-7

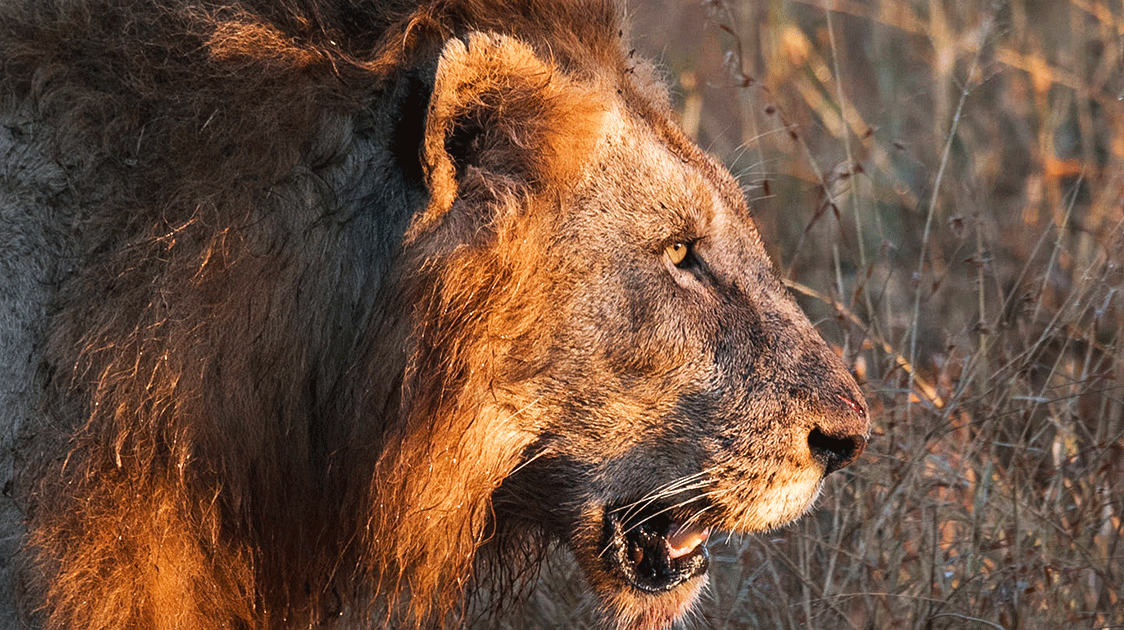

Why baobabs matter more than elephant numbers

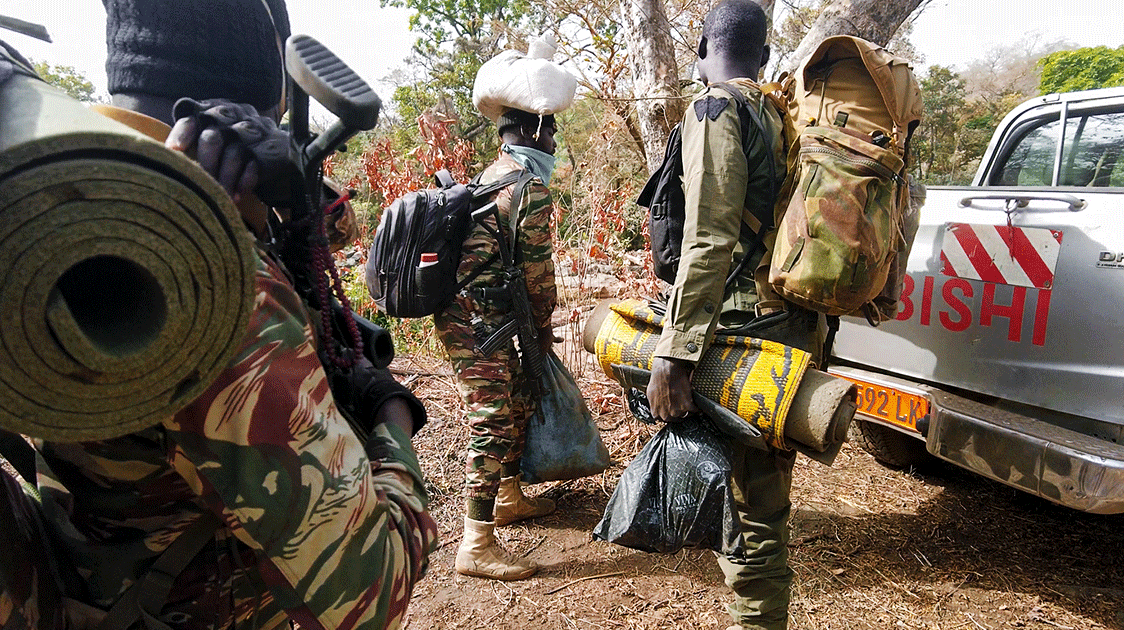

Elephant management policy in the Kruger (under the direct influence of IFAW-sponsored Rudi van Aarde) moved away from controlling numbers through culling to “waterpoint management".

Otherwise known as rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic.

The fate of the baobab is stark.

If baobabs are declining, it means browsing pressure is chronic, not episodic. It means landscape-scale refuges are failing. It means management policies are not working.

This is not a theory.

The decline of large trees under sustained elephant pressure follows a known ecological pattern in African savannas, where chronic browsing drives woodland loss and suppresses recovery over time (Western & Maitumo, 2004).

The danger of ignoring the warning

Tsavo shows what happens when the dead canary is ignored. Once large trees are lost across a landscape, the system shifts to a new state. Open savanna replaces woodland.

Shade, moisture retention, and habitat complexity are lost.

Even if pressure is later reduced, the trees don't magically return.

Kruger is not Tsavo.

Rainfall, soils, and management history differ. But the process is the same, and the baobabs are telling us the system is approaching, or may already have crossed, a threshold.

Management has failed to maintain ecological balance across space and time.

Healthy elephant populations can coexist with baobabs when:

- Elephant numbers are controlled.

- Movement is not artificially constrained.

- Pressure is distributed rather than concentrated.

But when these conditions are absent, baobabs die, and other, less celebrated species either precede or follow.

The uncomfortable truth

We’ve had adequate warning; baobabs don’t die quickly. When they begin to disappear, it’s late in the process.

By the time they are visibly declining, many other components of the ecosystem are already compromised.

The canary is choking.

Zimbabwean native Zig Mackintosh has been involved in wildlife conservation and filmmaking for 40 years. Over the years, he has traveled to more than 30 countries, documenting various aspects of wildlife conservation. The sustainable use of natural resources as an essential conservation tool is a fundamental theme in the film productions with which he is associated.