South Africa's Ruling Reignites the Rhino Horn Debate

By Dr Daniel Stiles

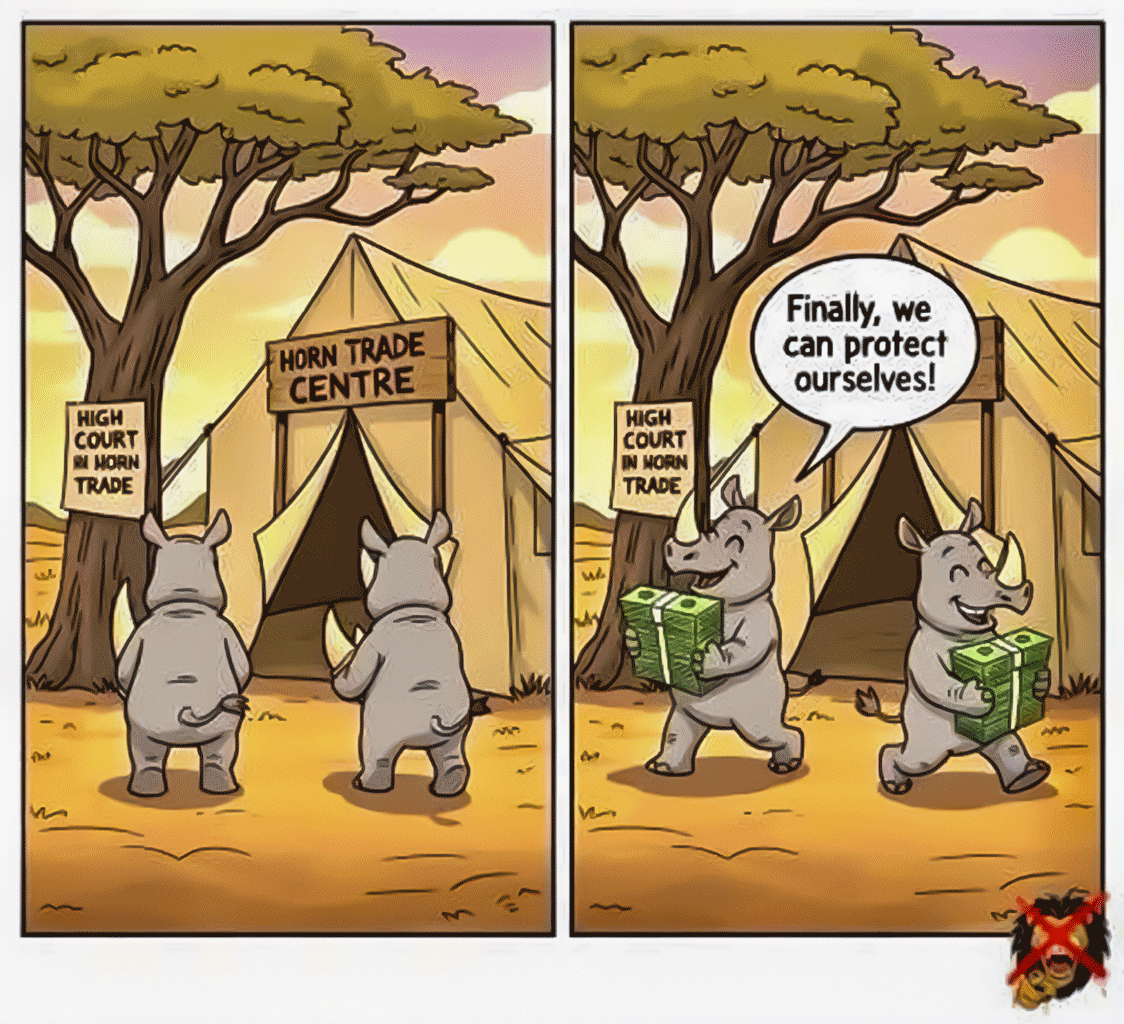

On 31st October, 2025, South Africa’s High Court in the Northern Cape ruled in favour of Hendrick Diedericks, owner of a registered rhino Captive Breeding Operation (CBO) in the Northern Cape known as Rockwood Conservation.

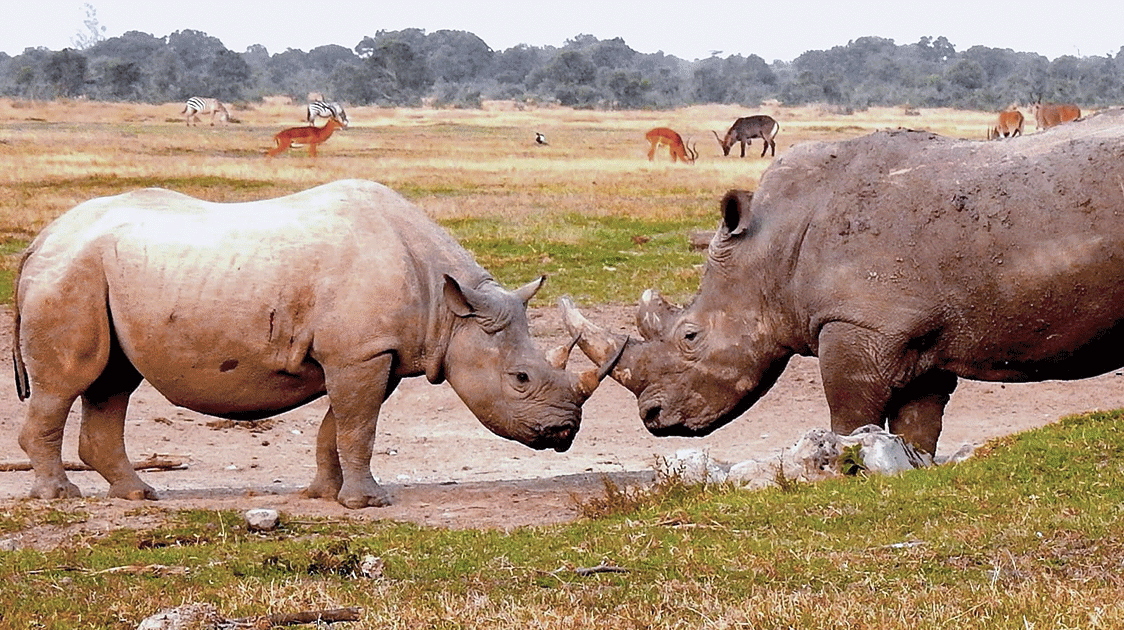

Starting with 45 southern white rhinos purchased from Kruger National Park in 2013, and obtaining fewer than 100 from other sources, Rockwood Conservation now has more than 450 rhinos.

To enable him to continue financing the considerable management and security expenses involved in ranching rhinos in a controlled environment, Diedericks has been attempting to trade his harvested horns from tranquilized rhinos to international buyers.

Export requires a CITES permit.

The provincial and national environment ministry authorities, which are in charge of wildlife trade policies and the issuance of CITES export permits, have refused to issue Diedericks CITES export permits.

Diedericks therefore sued the authorities, claiming that denying him the permits was contrary to South African law.

The case hinged on whether CITES Article VII, paragraph 5, was incorporated into South African law. The government claimed that it was not.

However, the court ruled that the CITES Articles in their entirety were incorporated into domestic law, and it agreed that Diedericks’ CBO qualified to export rhino horn taken from captive-bred white rhinos.

CITES Article VII.5 states “Where a Management Authority of the State of export is satisfied that any specimen of an animal species was bred in captivity or any specimen of a plant species was artificially propagated, or is a part of such an animal or plant or was derived therefrom, a certificate by that Management Authority to that effect shall be accepted in lieu of any of the permits or certificates required under the provisions of Article III, IV or V”.

The Ministry was ordered to decide on issuing a permit/certificate within 7 [working] days of the ruling, which was a deadline of 11 November 2025.

Derek Lewitton, owner of another South African rhino CBO, told Patrol that CITES Resolution Conference 12.10 (Rev.) further strengthened the breeders’ position with this paragraph: “NOTING that, in accordance with Article VII, paragraph 5, the import of specimens of Appendix-I species bred in captivity not for commercial purposes that are covered by a certificate of captive breeding does not require the issuance of an import permit and may therefore be authorized whether or not the purpose is commercial”.

This opens the door for commercial exports.

Diedericks, however, has said that he is not selling the horn to make a profit.

He told Patrol that he had spent millions of South African rand (1 USD = ~17 ZAR) on the protection and management of the rhinos and that without income, his CBO was not sustainable.

As happened with John Hume, the world’s largest rhino breeder, and many others, he would be forced to sell them off and stop the breeding entirely without financial support.

“I just want to be reimbursed for what I have invested and receive enough from horn exports to finance protection sustainably,” said Diedericks. “What I receive from horn sales has to be ploughed back into conservation, I’m not going to get rich out of this”.

Opposition

Reacting to press reports announcing the High Court decision, former Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE), Dr Dion George, said: “South Africa will not support any move to reopen the ivory or rhino horn trade. Our duty is to protect our wildlife, not to profit from their destruction".

In a statement, the DFFE confirmed that South Africa is fully committed to the international ban on the commercial trade of ivory and rhino horn.

“Our policy is guided by science, ethics, and global cooperation, not by commercial interest,” the statement said.

The department stressed that any suggestion that they seek to weaken international agreements or undermine collective conservation efforts is without basis.

“The DFFE’s priority is clear, and this is to secure a future where elephants, rhinos, and people can thrive together”.

Adam Cruise, an outspoken critic of legal wildlife trade, summed up why he thought the High Court ruling was a mistake:

“… this ruling could potentially establish a precedent that carries considerable risks. Once a legal export channel exists, enforcement agencies must distinguish legal horn from illegal horn in circulation, a task that has repeatedly proven unmanageable in the wildlife trade. Documentation can be forged, permits duplicated, and horns substituted or mixed during transport. The existence of a legal avenue gives illicit traders precisely the ambiguity they require,” wrote Cruise in the Daily Maverick.

Since there has never been a legal international rhino horn trade since the inception of CITES in 1975, one wonders what “task that has repeatedly proven unmanageable” Cruise is referring to.

Cruise also asserted that “… legal trade would normalise consumption and likely expand demand” and that “legalisation imposes an administrative and financial burden on enforcement agencies,” which they would be unable to meet because of the complexity of the horn tracing systems (DNA profiling, microchip verification, secure stockpile audits, etc.).

Despite the lack of any evidence supporting the arguments, many historically anti-wildlife trade NGOs agree with Cruise and oppose legal trade on the grounds that he lays out.

Historical Background

Wildlife sustainable use policy is well established in South Africa. Sport/trophy hunting, game meat farming, commercialization of wildlife products, live wildlife breeding and trade are just some of the practices that are legislated for and considered to be beneficial for biodiversity, habitats, and human wellbeing – if managed properly for sustainability.

All rhino species were listed in CITES Appendix I within two years of the launch of the Convention in 1975. Legal commercial international rhino trade has not been allowed for almost 50 years.

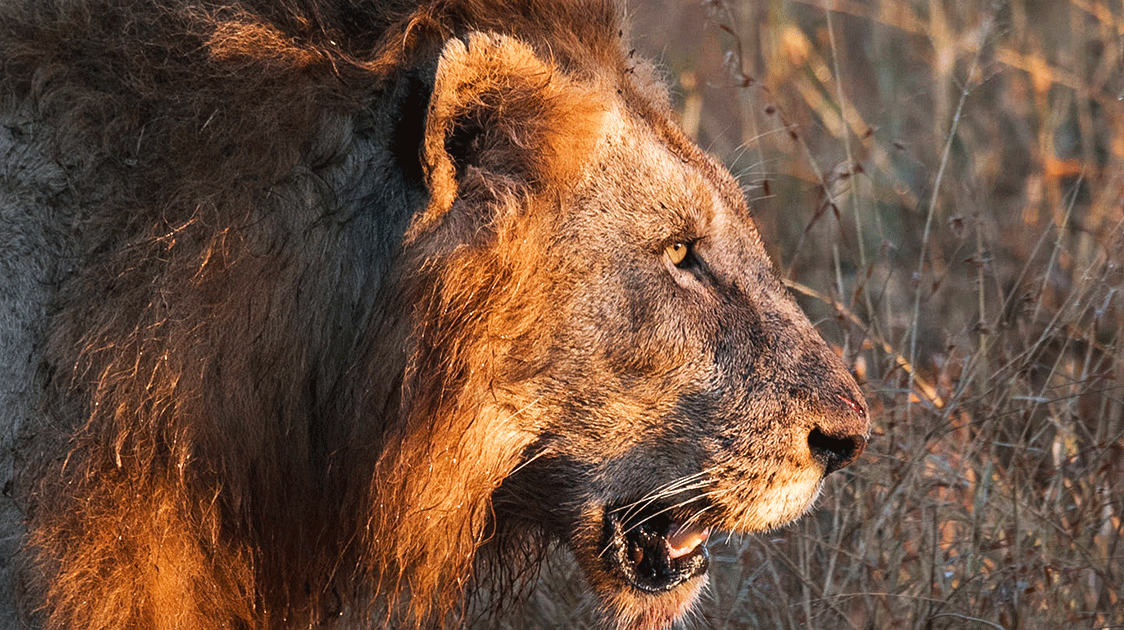

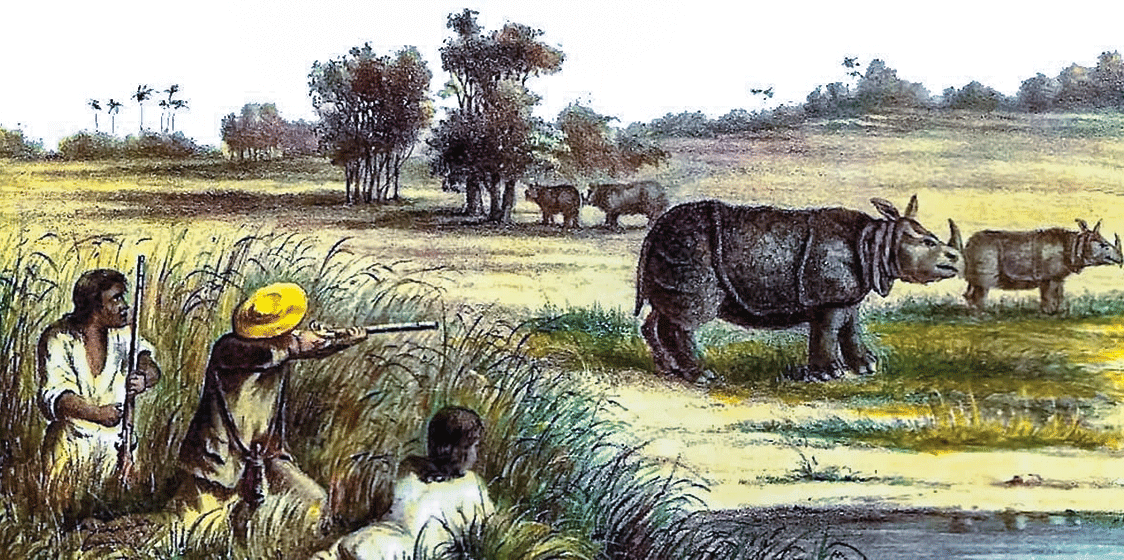

Demand for the horn, used mainly in the Far East as a fever-reducer, has existed for centuries, wiping out Asian rhino species, leaving only a few remnant patches here and there in Indonesia, Malaysia, India, and Nepal. Asian countries did not practice non-lethal horn offtake; the horns were obtained by killing the rhinos.

Supply began shifting to Africa legally in the 1950s, with the 1960s up to 1976 becoming a very important trade period.

Once CITES banned legal rhino horn exports, poached horn and horn leaked from stockpiles became the main sources to supply a growing market. Martin and Vigne in the early 1990s discovered a previously unknown large market in Yemen in which the horn was used to fashion jambiya (curved dagger) handles.

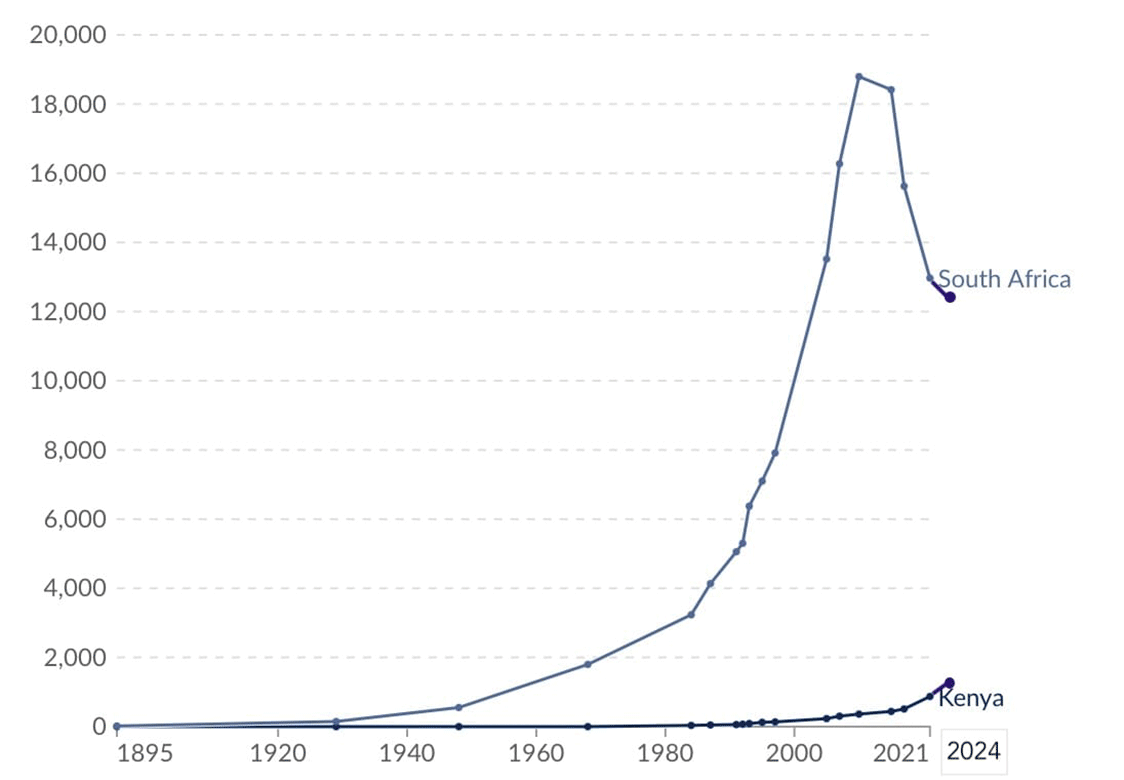

The poaching had a severe impact on rhino numbers, with Kenya’s population dropping from an estimated 20,000 in 1970 to just 550 in 1984.

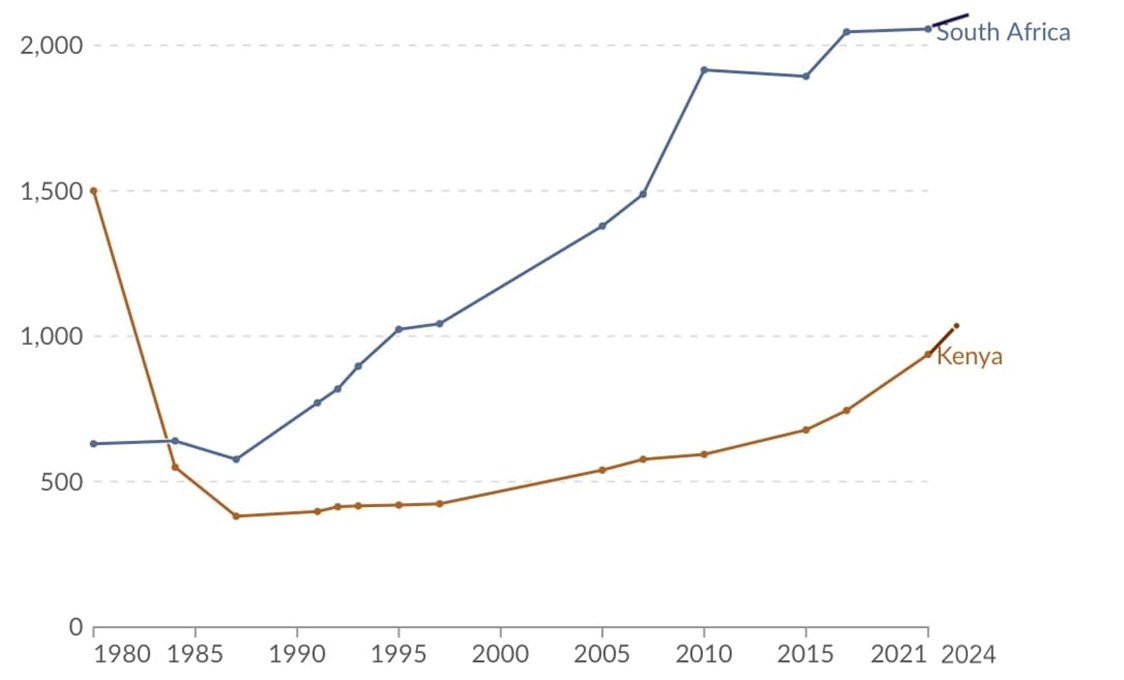

With sustainable use policies in place, South Africa’s southern white and black rhino populations increased until the poaching crisis years 2010-2017.

Figures 1 and 2 present the respective southern white and black rhino population trends of Kenya and South Africa. Kenya practices a protectionist, non-use wildlife policy.

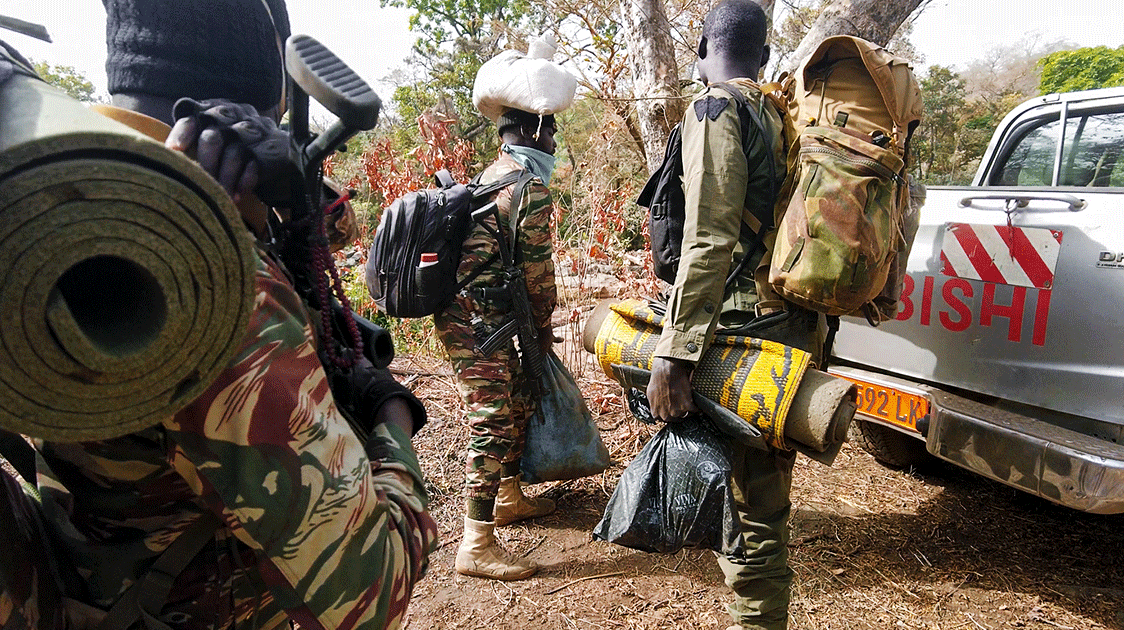

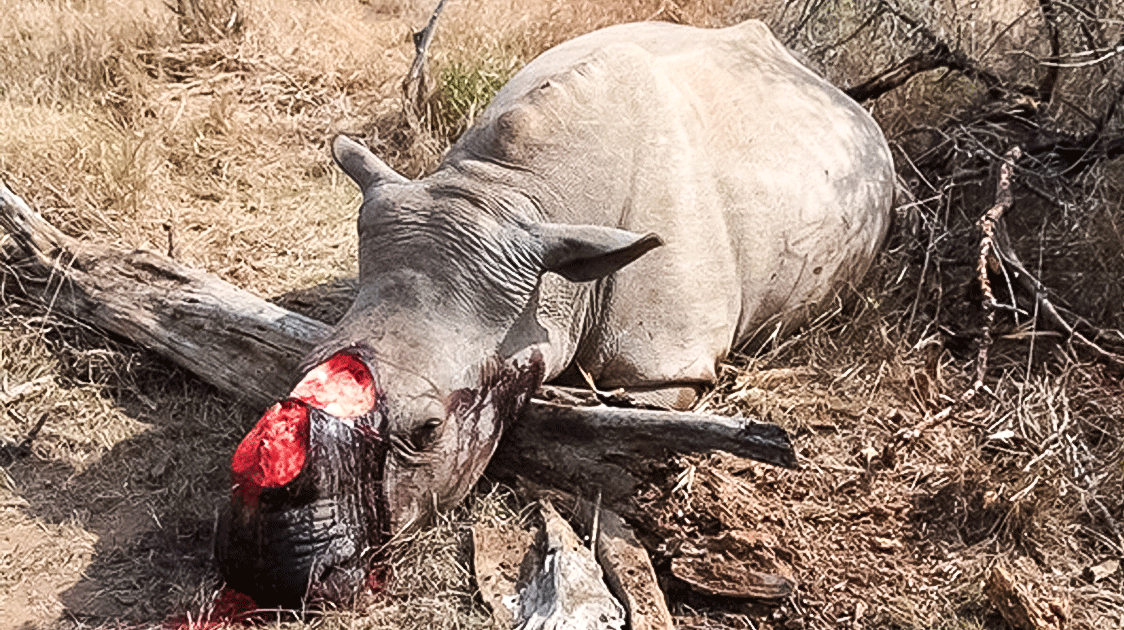

Poaching is still at a worrying level in South Africa, linked to the broader issue of legal international rhino horn trade.

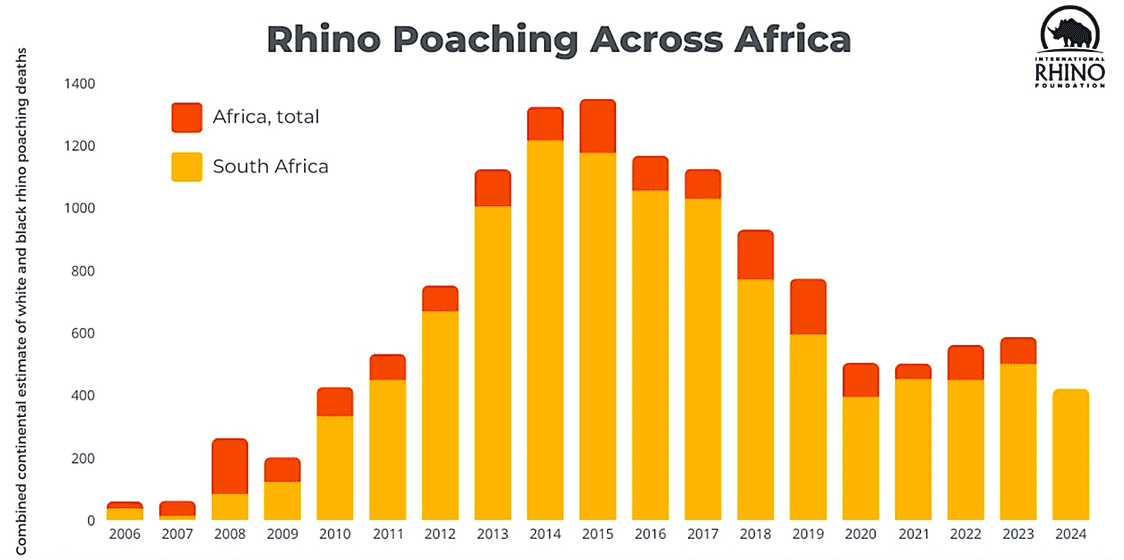

Rhino poaching 2020-2024 has stabilized to 400-500 a year from the peak of over 1,000 annually 2013-2017, but has still not returned to the pre-2010 levels of well under 200 a year (Fig. 3).

Rhino Ranching

Furstenburg et al. give an account of the history of captive rhino breeding beginning on state lands in the 1950s under the guidance of Ian Player and shifting progressively to private land from the 1960s onwards.

The study also assessed and quantified the impact of private wildlife ranching in South Africa with specific focus on its potential contribution to rhino conservation specifically for that of the southern white rhino (Ceratotherium simum simum).

It concluded that CBOs could sustain average annual population growth performances of 9.0% and that the weight of rhinoceros horn that could be obtained from CBO production varied from 5,319–13,356 kg per annum, at 2021 population levels.

If horn exports were to be allowed, presumably many more game ranchers would register as CBOs and begin breeding white rhinos, increasing annual production.

In addition, in 2020 government stockpiles of rhino horn totalled 27.6 tonnes and private stockpiles totalled 45.5 tonnes.

Derek Lewitton told Patrol that the private stockpile was up to about 60 tonnes today, but only those horns owned by CBOs would qualify for export under the court ruling and CITES regulations.

Obtaining rhino horn from captive rhinos does not require killing them.

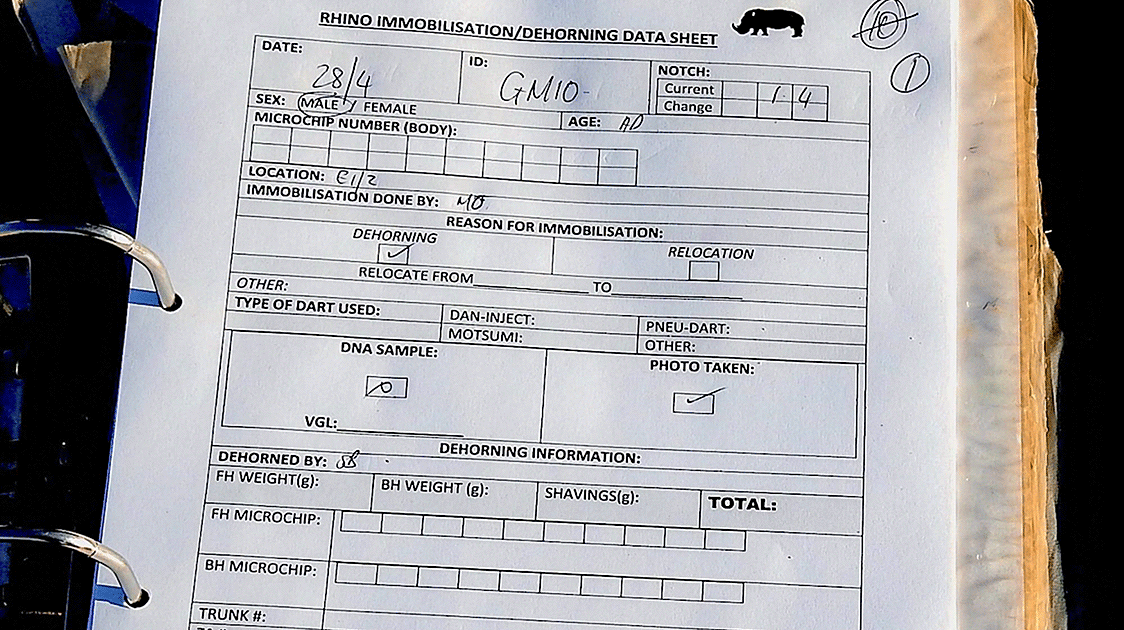

The top part of the horn, made up of keratin and devoid of blood vessels, makes dehorning the equivalent of a haircut or nail clipping in humans. The rhino is tranquilized, and a team moves in to cut off 1-2 kg of top horn.

To trim horns, the CBO must first obtain a series of permits – one to trim, one to possess the horn, another to transport it to safe storage.

The trimming may only be done under strict supervision by a provincial wildlife official, and the darting can only be done by a licensed wildlife veterinarian.

Each harvested horn must be registered with the Rhino DNA Index System (RhODIS), along with a DNA sample.

This can be used to ensure that only legally sourced rhino horn enters the legal trade, or provide evidence of illegal trade in the case of seizures.

Many critics of legal trade argue that laundering would occur, i.e. poached horn would be mixed in with legal horn.

If South Africa, and any other African countries who decide to employ the same approach as Diedericks, practice due diligence in verifying that each horn exported is registered with RhODIS, and the import country does likewise, laundering should not occur, in spite of Adam Cruise’s doubts.

The combined annual rhino horn production, along with gradual release of eligible stockpiled horn, could potentially supply all of the demand from eligible buyers, who presumably will be in Asia. Legal supply satisfying demand has been another major concern of legal trade critics.

“Each animal produces barely 1 kg of horn a year, while demand in Asia runs into thousands of kilograms. No ‘sustainable harvest’ can meet that — the gap would be filled by poaching and laundering,” asserts one critic, which is representative of the view.

However, the gap without legal trade is already filled by poaching and laundering, so it is difficult to understand the logic of this argument.

Current demand is filled now 100% by illegal horn. This proportion would be reduced by whatever percentage of the market was satisfied by legal horn, thus reducing poaching.

According to Lewitton, “Roughly 13 tonnes of horn are trimmed every year, and more than 100 tonnes of horn already sit in storage.

With annual consumption repeatedly measured at roughly five tonnes per year, the numbers do not support any claims of demand outstripping legal supply”.

Few countries today allow import and use of rhino horn, so initially, in the process of establishing legal rhino horn trade, it would be expected that export quantities would be relatively low.

“Demand for horn is no threat to the survival of the rhinos”, Derek Lewitton told Patrol. “It is how we respond to that demand that determines whether we save the animals or fail them.

If we put the demand to use generating funds to protect our rhinos, as well as encouraging more reserves to join the effort of keeping rhinos, then we will see that Asian consumption of horn is an immense gift to conservation.

But if we surrender the field to those who will kill our rhinos and keep the horn profits for criminal syndicates, then demand will have fueled the extinction.”

The abhorrence of commodification of wildlife and treating it like livestock is at the crux of the anti-use ideology – the general public and the NGOs that serve it find the sustainable use approach offensive and immoral.

They wish to see wild animals “roaming free and living their lives unmolested by human greed”.

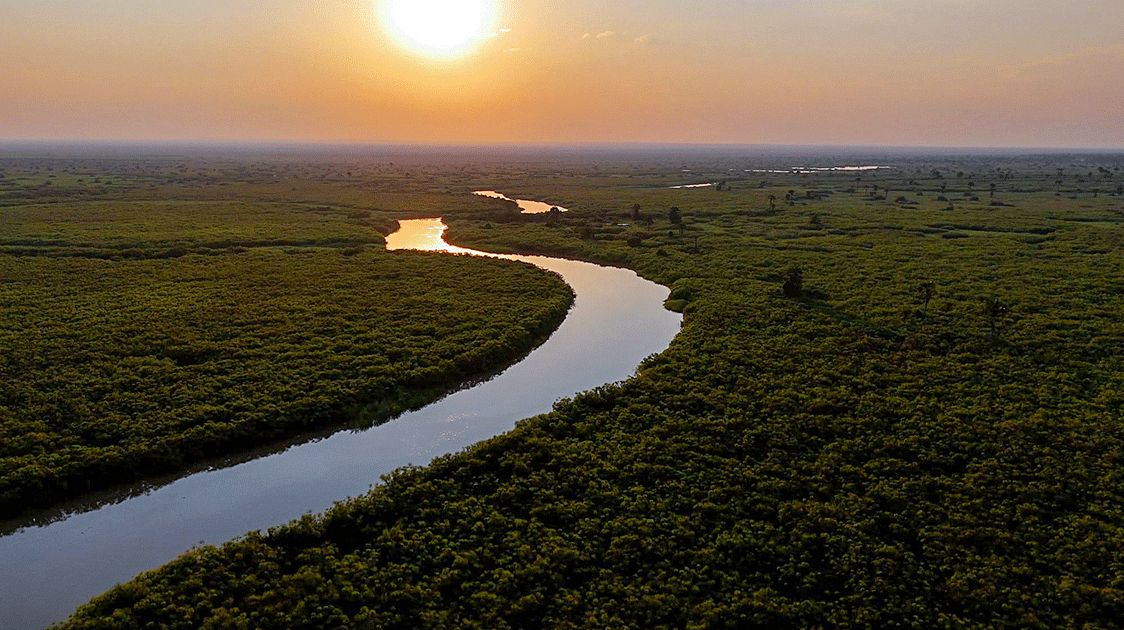

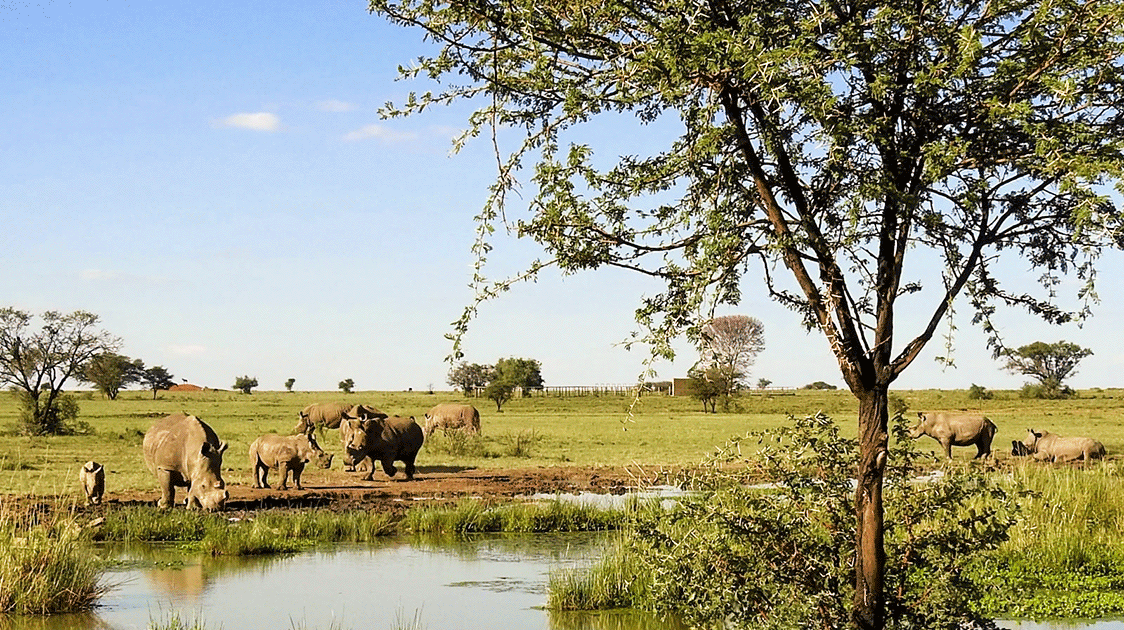

According to Lewitton and Diedericks, their rhinos are roaming free.

Says Lewitton, “Anyone who bothers to visit Wicus’s [Diedericks] farm, or mine, immediately understands that our animals are as wild as anything in Kruger.

Anything less than that would put us in violation of the standards we are compelled to uphold under South African regulations for rhino breeding facilities.

Our animals roam thousands of acres of completely wild African bush. They mate with whomever they choose”.

The PR war

There is a tremendous amount of animus directed towards those engaged in wildlife sustainable economic use by what in shorthand has come to be known as the “ARs” – animal rights advocates.

Not all those who oppose legal wildlife trade technically are animal rights advocates, but there exists a broad basket of people who share a common belief that animals should be treated kindly, not be subjected to harm or pain, and this includes not being used for any economic purpose because they have intrinsic value.

Adam Cruise echoes the prevailing AR view, arguing that the choice is between “whether wild animals are commodities to be warehoused, slaughtered and sold by the kilo, or living beings embedded in ecosystems that deserve protection for their own sake”.

However, in the case of rhino horn trade, the rhinos are not slaughtered. And they are protected.

The protection is provided by private landowners without utilizing any public funds, which means that more money is available for other public services provided by the government such as health and education.

In government-protected areas, where the great majority of poaching takes place, protection is provided by the state, diverting funds away from public services.

Don Pinnock is another anti-trade journalist who said that the court decision to allow horn trade “is about the soul of environmental governance in South Africa,” adding that “the lines between conservation and commerce have all but dissolved”, implying that commerce (i.e. trade) is unrelated to conservation.

Ivo Vegter, a pro-sustainable use writer, in reaction to Pinnock’s observation stated that, “Pinnock is right. It is about the soul of environmental governance in South Africa, and whether the environment is governed for its own sake, or for the sake of the people of South Africa.

There should not be “lines between conservation and commerce”.

Vegter went on to say that “Without commerce, conservation is unsustainable. Without conservation, wildlife-related commerce is unsustainable.

Each needs to thrive for the other to succeed. Each needs to thrive in order to benefit the people of South Africa who have an interest in wildlife and the natural environment”.

The sustainable use approach is more equitable and beneficial to both society and wildlife because a reciprocal relationship is established.

The trade prohibitionists deny society access to natural resources, which runs counter to the fundamental principles laid out in the World Conservation Strategy, published in 1980 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the United Nations Environment Programme and the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF), and the Convention on Biological Diversity of 1992, which South Africa has signed and ratified.

The Convention on Biological Diversity is a UN treaty focused on conserving biodiversity, sustainably using its components, and fairly sharing benefits from biodiversity resources. Its key objectives are:

- Conservation: Protecting biodiversity at all levels (ecosystems, species, genetics).

- Sustainable Use: Using biological resources in a way that doesn't deplete them.

- Benefit Sharing: Ensuring fair and equitable sharing of benefits from using genetic resources.

Genetic resources include rhino horn. The anti-trade, anti-use movement denies the principles embedded in both international conventions and South African law.

A New Economic Paradigm

In South Africa, one could legitimately argue that benefit sharing among all segments of society is currently not fair and equitable.

For mainly historical reasons, wildlife economic production and benefits are concentrated in the hands of white South Africans, who dominate the various sustainable use organizations and who comprise the rhino breeders and others in the commercial wildlife sector.

There is considerable potential to engage what IUCN has coined Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLC) in rhino breeding and horn trade, along with other areas of the wildlife economic sector.

What are defined today as IPLCs have been trading wild natural resources for centuries, supplying empires around the world with a cornucopia of wild animal and plant products.

Colonialism and the dramatic shift in social, economic and political systems in its aftermath have largely disrupted the international trading system that once existed.

Government policy and strategically allocated resources could create a new natural resource economy involving IPLCs based on the principles of sustainable use and development.

A wildlife-based economy, including rhino horn trade, is an example of what UNEP has defined as an Inclusive Green Economy in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication.

As UNEP states, “such an economy is low carbon, efficient and clean in production, but also inclusive in consumption and outcomes, based on sharing, circularity, collaboration, solidarity, resilience, opportunity, and interdependence”.

Communal lands could become areas of biodiversity regeneration and wildlife growth, given the appropriate government policies and resource allocations.

The wildlife private sector could assist significantly in this transformation by forming collaborative partnerships to provide training, capacity building and investment.

Where to Now?

Both the provincial and national Environment departments that Diedericks sued have applied for leave to appeal the High Court’s decision.

Their application will be heard in March 2026, with a ruling expected almost immediately after.

Diedericks has not opposed their application for the right to appeal, as he and Lewitton believe a ruling of this magnitude deserves to be endorsed by South Africa's Supreme Court of Appeals and, thus, placed beyond further challenge.

Having said that, it is entirely possible that the court will deny them the right to appeal, as the legal issues in this matter are quite clear – CITES Article VII, paragraph 5 is part of South African law.

All parties will proceed on the basis of the court's ruling.

Dr Stiles started out in anthropology and archaeology, researching past and present natural resource use among hunter-gatherers and pastoralists, and later moved to the UN system, working on desertification control. In 1999, he began investigating wildlife trade, producing reports and publications for UN agencies, the IUCN, TRAFFIC, and various NGOs.