Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) in African Conservation

Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) is an approach to conservation that recognizes the economic value of ecosystem services and creates financial incentives for their protection.

PES involves transactions where a beneficiary or user of an ecosystem service makes payments to individuals or communities whose land management decisions affect the provision of these services.

The basic premise is that the beneficiaries of those services should compensate those who provide environmental services.

Key Ecosystem Services in African PES Programs

- Carbon sequestration and storage (forests, grasslands)

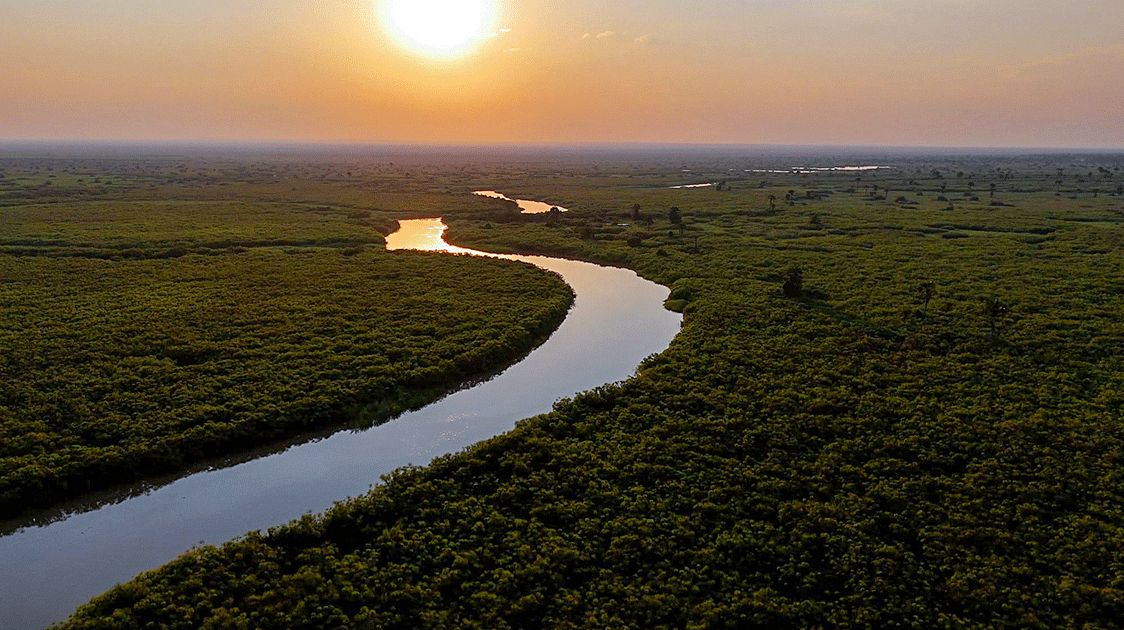

- Watershed protection and water quality

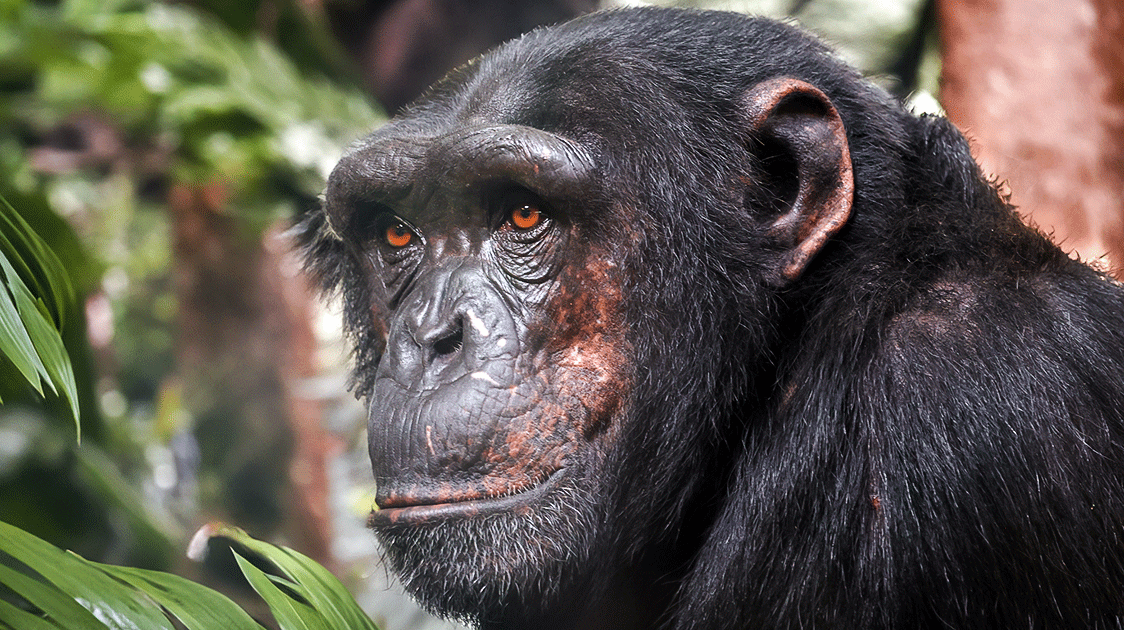

- Biodiversity conservation

- Soil fertility maintenance

- Cultural and landscape services

Implementation Models in Africa

Government-financed PES

National governments establish programs where they act as the buyer of ecosystem services on behalf of their citizens. South Africa's Working for Water program is a prime example, employing people to remove invasive plant species to improve water security.

User-financed PES

Direct transactions between service users and providers. For instance, downstream water users (like utilities or beverage companies) pay upstream communities to maintain forest cover and prevent erosion.

Compliance-based PES

Companies offset their environmental impacts through payments to conservation initiatives. The REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) programs in countries such as Tanzania, Kenya, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo exemplify this approach.

Voluntary markets

These include ecotourism fees, carbon credits, and biodiversity offsets, where buyers voluntarily participate without regulatory requirements.

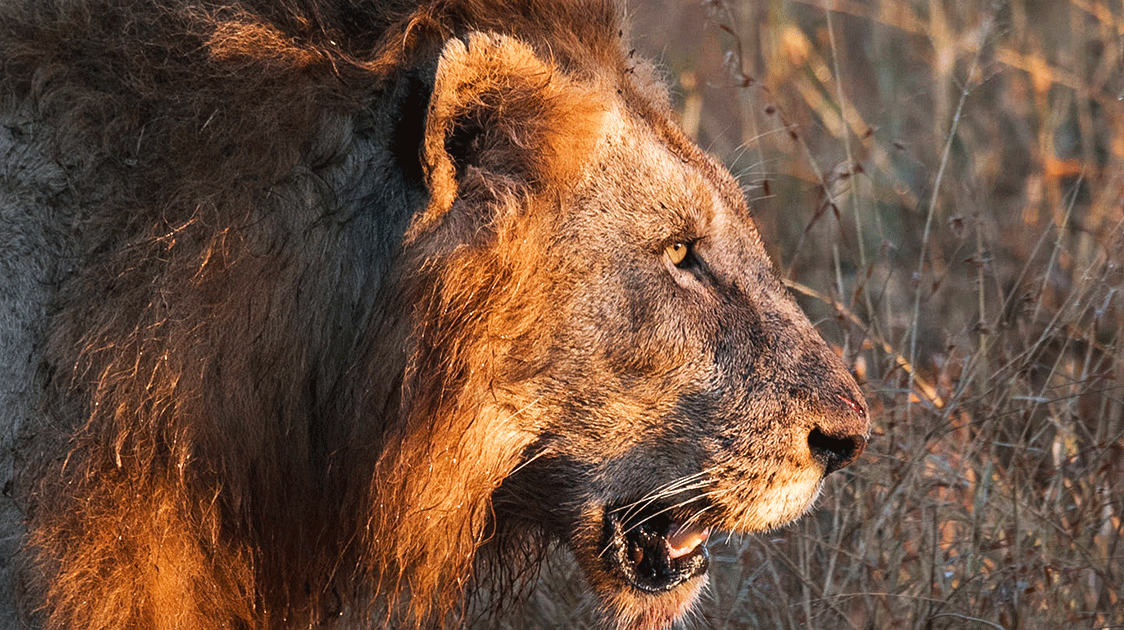

African Safari Hunting PES Programs: Conservation Through Community Revenue Sharing

African countries have pioneered Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) programs that directly link safari hunting revenues to community-based conservation, creating powerful economic incentives for wildlife protection across over 500,000 km² of habitat and benefiting millions of rural residents.

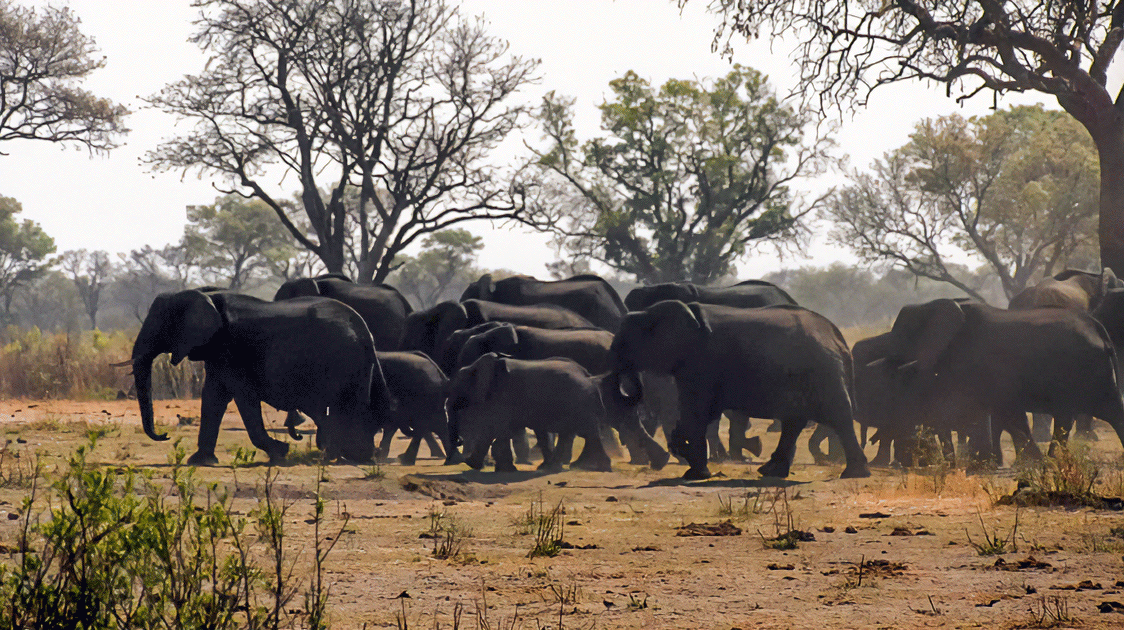

These programs demonstrate that when communities receive substantial, direct payments from hunting tourism, they become effective stewards of wildlife and ecosystems, leading to remarkable conservation successes, including recoveries for endangered species such as elephant and black rhinos, habitat restoration, and reduced poaching across multiple countries.

The most successful models concentrate in southern Africa, where countries like Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Zambia have developed sophisticated revenue-sharing mechanisms that transfer USD 10 to 20 million annually to rural communities.

However, effectiveness varies dramatically based on governance quality, revenue retention rates, and the degree of community control over wildlife resources.

Namibia leads the world in hunting-based conservation success

Namibia's communal conservancy program represents the gold standard for hunting-based PES, covering 86 conservancies across 166,179 km² (20% of the country) with 227,802 community members.

The program generates over N$132 million (approximately USD 10 million) annually in direct cash and in-kind benefits, with hunting contributing approximately N$35 million (26% of total revenue).

The payment mechanism is remarkably straightforward: 100% of hunting revenues flow directly to conservancies with no government retention.

Trophy hunting fees range from USD 12,376 per elephant with tusks over 40 pounds to USD 300 to 380 per hunter per day for general hunting.

The Nyae Nyae Conservancy exemplifies this success, generating USD 430,000 annually (86% from hunting) and distributing USD 120 per member, the only conservancy able to afford direct cash payments to all its members.

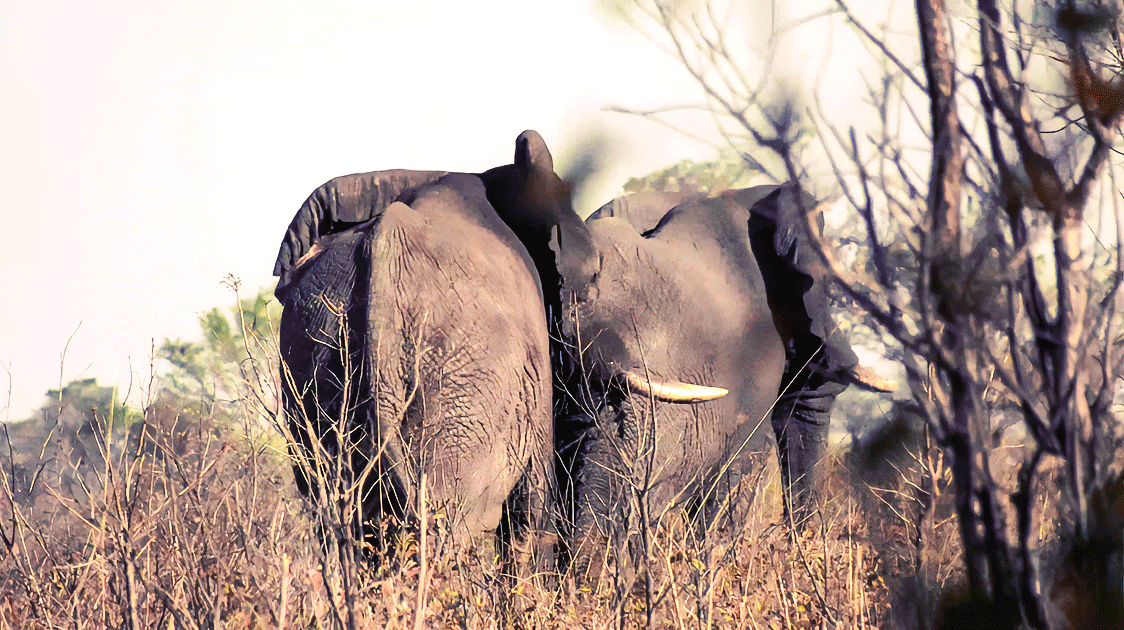

Conservation outcomes are spectacular. Elephant populations increased from 7,600 to 23,600 (a 210% increase) between 1995 and 2016, while black rhinos recovered from near extinction to become the world's largest free-roaming population.

Desert lions increased from fewer than 25 to over 150 individuals, and plains game populations increased tenfold. The program employs 763 game guards and achieved a 60% reduction in poaching incidents in 2019.

Zimbabwe's CAMPFIRE demonstrates both potential and vulnerability

Zimbabwe's Communal Areas Management Program for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) operates across 36 districts, covering 12 million acres, and has historically generated USD20 million for communities between 1989 and 2001, with 89% of the revenue coming from sport hunting.

The program benefits 2.4 million people across 200,000 households directly and 600,000 households indirectly.

Recent revenue sharing has improved significantly. Zimbabwe reformed its system in 2022 to give 100% of hunting revenue directly to communities, up from the previous 52-60% split.

From 2009 to 2016, the program generated a total of USD 11.9 million, with USD 6.4 million distributed to communities. However, peak revenues of USD 2.2 million in 2013 dropped to USD 1.7 million between 2014 and 2016 due to US import restrictions on elephants.

CAMPFIRE's conservation impact includes maintaining Africa's second-largest elephant population (82,000+ animals) and supporting extensive community infrastructure, including schools, clinics, and boreholes.

However, the program faces significant challenges from political instability, corruption, and elite capture, which have undermined its effectiveness in certain areas.

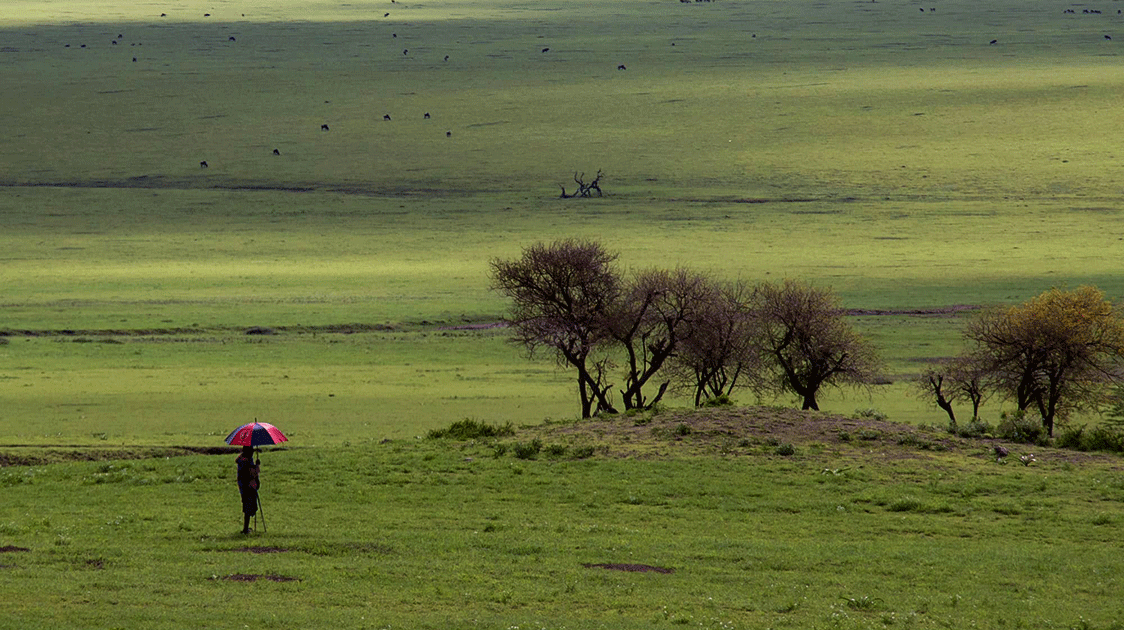

Tanzania's mixed results highlight governance challenges

Tanzania operates 22 Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs), which cover approximately 7% of the country's land area. Communities receive 50% of the WMA revenue and 25% of the hunting block fees. The top five WMAs earned USD 3.55 million between 2016 and 2018, with USD 950,000 from hunting tourism and USD 2.6 million from photographic tourism.

Burunge WMA generated USD 248,000 in 2014, providing approximately USD 7 per person annually to 36,000 inhabitants. Makame WMA averaged USD 97,210 annually from 2014 to 2019, increasing to USD 144,000 in 2020-21 with expanded hunting opportunities.

These funds support 60+ students in universities and various community development projects.

However, Tanzania's centralized approach limits community autonomy. The government retains significant control over wildlife management decisions, and most WMAs fail to generate substantial tourism revenue, leading to minimal direct benefits for participating households.

Kenya pioneered non-hunting conservancy models

While Kenya banned hunting in 1977, it developed innovative conservancy-based PES models that demonstrate alternative approaches to wildlife-based payments.

24 Maasai Mara conservancies, covering 400,000 acres, generate USD 20 million annually from tourism, with 50% of the revenue flowing to communities through monthly lease payments and bed-night levies of USD 17 to USD 70 per person.

The Northern Rangelands Trust operates 39 conservancies covering approximately 42,000 km² (8% of Kenya) and manages over 350,000 people. Beyond tourism revenue, these conservancies earned USD 3.9 million from carbon credits in 2023, demonstrating the diversity of PES mechanisms.

Kitenden Conservancy receives USD 1.2 million annually in lease payments for 26,000 acres, while Ol Kinyei Conservancy has achieved the highest lion population densities in Kenya.

These models indicate that 30% of Kenya's wildlife now resides in conservancies, with wildlife densities often exceeding those found in national reserves.

Payment mechanisms vary significantly across programs

Direct cash payments represent the most transparent mechanism, with Namibia's Nyae Nyae Conservancy providing the only example of universal per-capita distributions (USD120 annually per member).

Most programs, however, use employment-based payments, with Namibia employing over 1,400 tourism staff, more than 700 game guards, and 300 support staff.

Revenue-sharing formulas show dramatic variation. Namibia retains 100% of hunting revenue at the community level, while Zimbabwe recently moved to 100% community retention from a previous 52-60% split.

Tanzania provides 25-50% of the proceeds, depending on the program type, while Botswana historically offered only 15% before its 2014 hunting ban.

Trophy fee structures create substantial revenue streams. Elephant hunting generates USD 12,376 per animal in Namibia, while Zimbabwe's hunting quota includes high-value species such as elephants, buffalo, and lions.

Zambia's Game Management Areas distribute 50% of the trophy fees to communities, along with over 6,000 kg of game meat, annually.

Conservation outcomes show remarkable wildlife recoveries

Quantitative wildlife data demonstrate significant conservation success where programs function effectively.

Namibia's elephant population has tripled from 7,600 to 23,600 animals, while Zimbabwe maintains a population of over 82,000 elephants despite facing political challenges.

Black rhino populations in Namibia have recovered from near extinction to stable, growing populations.

Habitat protection achievements are equally impressive. Namibia's conservancies protect 20% of the country, while Zimbabwe's CAMPFIRE covers 12 million acres.

Kenya's conservancies protect 86,864 km² (17% of the country), and Tanzania's WMAs cover 7% of the national territory.

The effectiveness of anti-poaching efforts correlates strongly with community economic incentives.

Namibia achieved a 60% reduction in poaching, while areas with strong community revenue streams consistently show lower poaching rates than adjacent areas without such incentives.

Governance challenges undermine program effectiveness

Elite capture represents the most significant challenge across all programs. Benefits are frequently concentrated among community leaders and wealthier households, with women receiving disproportionately fewer benefits despite bearing the costs of human-wildlife conflict.

Geographic disparities mean remote conservancies often receive higher per-capita benefits than accessible areas.

Corruption and mismanagement particularly affected Zimbabwe's CAMPFIRE program, where political elite land seizures disrupted conservation areas and revenue diversion reduced community benefits.

Tanzania's bureaucratic complexity limits community autonomy and reduces program effectiveness.

Market dependencies create vulnerabilities across all programs. COVID-19 devastated tourism-dependent areas, while US elephant import restrictions significantly reduced hunting revenues.

Exchange rate volatility affects international payments, particularly impacting dollar-denominated hunting fees.

Success factors emerge from comparative analysis

Secure resource rights represent the most critical success factor. Namibia's full devolution of wildlife rights to communities is correlated with the strongest conservation and economic outcomes, whereas Tanzania's centralized control limits effectiveness. Zimbabwe's conditional rights through the Rural District Councils create intermediate outcomes.

Revenue retention rates directly correlate with program success. Namibia and Zimbabwe's 100% community retention rates produce better outcomes than Tanzania's 25-50% retention rates or Botswana's historical 15% retention rate.

Democratic governance structures with transparent decision-making consistently outperform top-down management approaches.

Technical capacity and diversified income streams enhance program sustainability.

Namibia's combination of hunting, tourism, and emerging carbon credit revenues provides resilience against market shocks. Kenya's diversified conservancy model demonstrates alternative approaches when hunting is not available.

Policy recommendations for enhanced effectiveness

Institutional design should prioritize secure, long-term resource rights for communities with a focus on maximizing revenue retention locally. Democratic governance structures with transparent benefit-sharing mechanisms consistently outperform alternatives.

Capacity building in wildlife management, business skills, and governance proves essential for long-term success.

Market diversification reduces vulnerabilities to external shocks. Kenya's carbon credit revenues and multiple tourism revenue streams provide models for risk reduction.

International cooperation on trade policies and development funding can support the establishment and sustainability of programs.

Equity mechanisms must address gender inequality and elite capture through pro-poor targeting and conflict resolution systems. Monitoring and evaluation systems should track both conservation outcomes and the distribution of benefits to ensure that programs achieve their dual objectives.

Conclusion

African hunting-based PES programs demonstrate that economic incentives can drive conservation success when properly designed and implemented.

The evidence shows dramatic wildlife recoveries, substantial community benefits, and effective habitat protection across multiple countries and contexts.

However, success depends critically on the quality of governance, revenue retention, and community rights.

Namibia's model provides the strongest template for success through full rights devolution, 100% revenue retention, and democratic governance.

Zimbabwe's CAMPFIRE shows both the potential and vulnerability of such systems, while Tanzania's experience highlights the limitations of centralized approaches.

Kenya's conservancy model provides viable alternatives when hunting is not an option.

The future of these programs depends on addressing governance challenges, diversifying revenue streams, and ensuring equitable distribution of benefits.

When these conditions are met, hunting-based PES can provide sustainable financing for conservation while delivering significant economic benefits to rural communities, creating powerful incentives for long-term ecosystem stewardship across Africa's critical wildlife habitats.