No Bullet, No Buffer: Why Wildlife Corridors Disappear When Hunters Do

By Zig Mackintosh

Biogeography, the study of species distribution patterns across space and time, is seldom discussed in African conservation.

Yet it provides perhaps the most compelling context for understanding why safari hunting concessions matter to conservation, and why, if safari hunting is eliminated, the risks to biodiversity would be immeasurable.

The Theory of Island Biogeography, developed in the 1960s by Robert MacArthur and E.O. Wilson, shows that small, isolated habitat patches support fewer species, maintain smaller populations, and face a higher risk of local extinction.

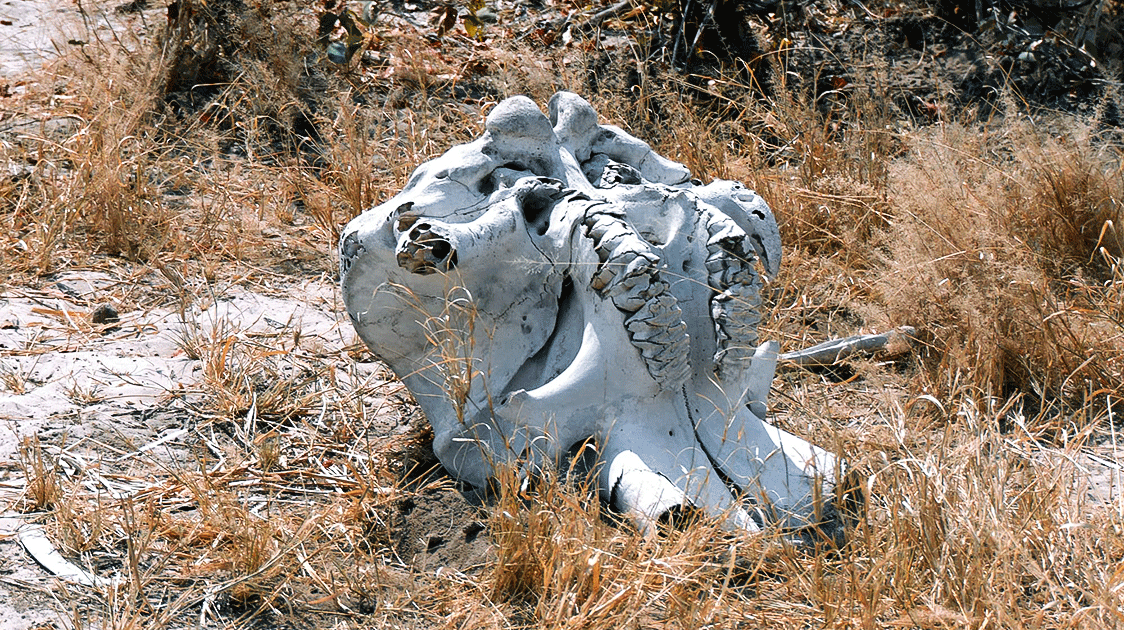

Genetic diversity is the raw material of evolution. It determines a population’s capacity to adapt to disease, environmental change, and novel stressors.

When populations become isolated, they lose genetic variation through drift and inbreeding. The effects may take decades to manifest, but they are predictable and, without intervention, irreversible.

Fragmentation

Across Africa, human activities such as agriculture, mining, roads, fences, and settlements have fragmented once-continuous wildlife landscapes. These fragments act as ecological islands, making populations highly vulnerable.

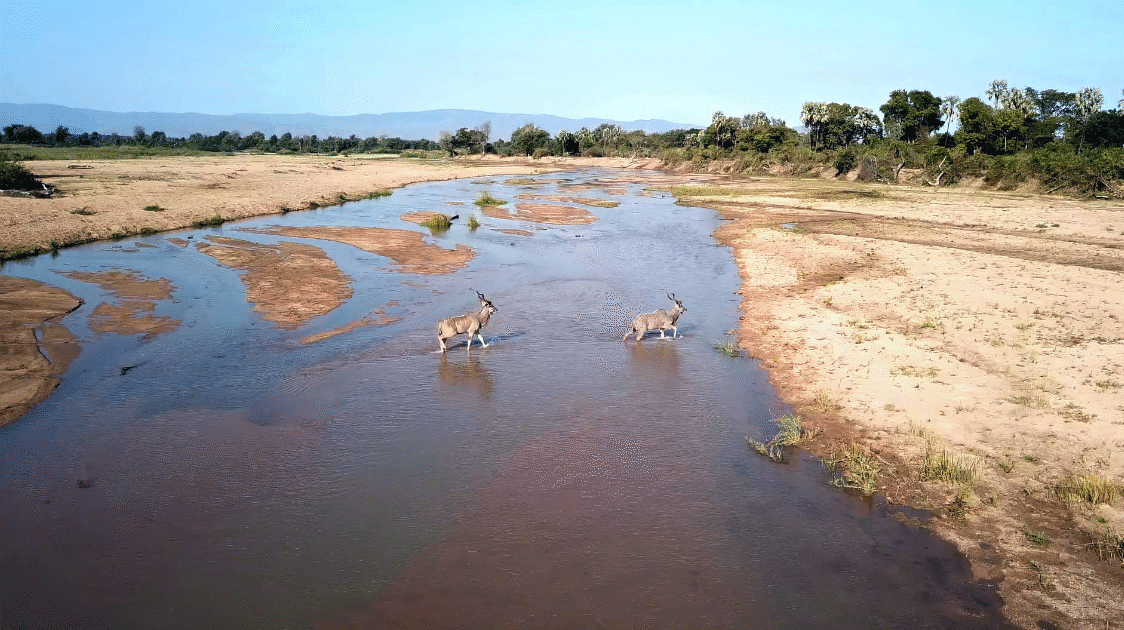

A wildlife corridor is a region of habitat that connects otherwise separated areas, allowing animals to move between them. Corridors support dispersal, seasonal migrations, gene flow, and recolonization after local declines.

Regulated safari hunting and community conservancy areas function as effective corridors when managed to maintain sufficient vegetation cover, water sources, and low levels of disturbance.

Functional connectivity requires that the corridors operate effectively, with community involvement and incentive systems, to ensure that they are not just shaded areas on a map.

The Selous-Niassa Wildlife Corridor is a good example.

The Role of Safari Hunting

The most comprehensive assessment of safari hunting’s role in conservation was published by Lindsey, Roulet, and Romañach in Biological Conservation in 2007.

Their findings established that, at the time, approximately 1.4 million sq km were used for safari hunting across sub-Saharan Africa, an area 22% larger than the combined national park estate.

The implications are explicit: remove safari hunting as a viable land use, and this 1.4 million sq km must either transition to alternative conservation funding (which rarely materializes at comparable scales) or convert to agriculture, settlement, or unmanaged exploitation.

What transpired in Tanzania clearly illustrates this.

A 2012 study in PLoS ONE by Lindsey et al. assessed the significance of lion hunting for the financial viability of trophy hunting across five African countries.

At the time, lions generated 5 to 17% of gross safari hunting income, attracting the highest mean prices of all trophy species, USD 24,000 to USD 71,000.

The study’s critical finding concerned landscape-level effects. Loss of lion hunting would reduce the competitiveness of wildlife-based land uses relative to ecologically unfavorable alternatives.

In practical terms, without lion revenue, some hunting areas would no longer be economically viable as wildlife habitat. The land would face pressure to convert to other uses.

This relates directly to the corridor function.

If hunting concessions surrounding national parks lose viability, the parks become increasingly isolated, true islands rather than nodes in a connected landscape.

The biogeographic predictions follow. Declining species richness, loss of genetic connectivity, and increased vulnerability to local extinction.

Proving the Theory

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) enthusiastically stepped in to show how this works in practice by listing the African lion “threatened” on the endangered species list in 2016.

Special import permits for lion trophies were now required and, critically, would only be issued for lions hunted in concessions that had implemented a “scientifically sound” lion conservation management plan.

There was no grace period during which the necessary compliances could be met.

Tanzania wasn’t rejected outright but rather something far worse.

It was placed in an indefinite review status along with Namibia and Mozambique, while limited permits were issued for Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The uncertainty about which concessions would qualify for import permits led to bookings collapsing and an immediate cash crunch for safari operators, as American hunters accounted for over 70% of the global market for trophy imports.

In October 2016, Conservation Force made an extensive submission to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in support of applications for permits to import lion trophies from Tanzania, nearly a year after the listing, documenting contributions from 27 operators protecting over 121,000 sq km.

But the approval process dragged on for three years until the first lion trophy permit was finally issued in 2019.

By the time permits began trickling through on a case-by-case basis, the damage was done.

Many outfitters had surrendered their hunting leases to the government as their concessions were no longer financially viable.

The Tanzanian government was theoretically responsible for managing these abandoned wilderness areas, but in reality, it lacked the resources to do so.

And then political opportunism stepped up to the plate.

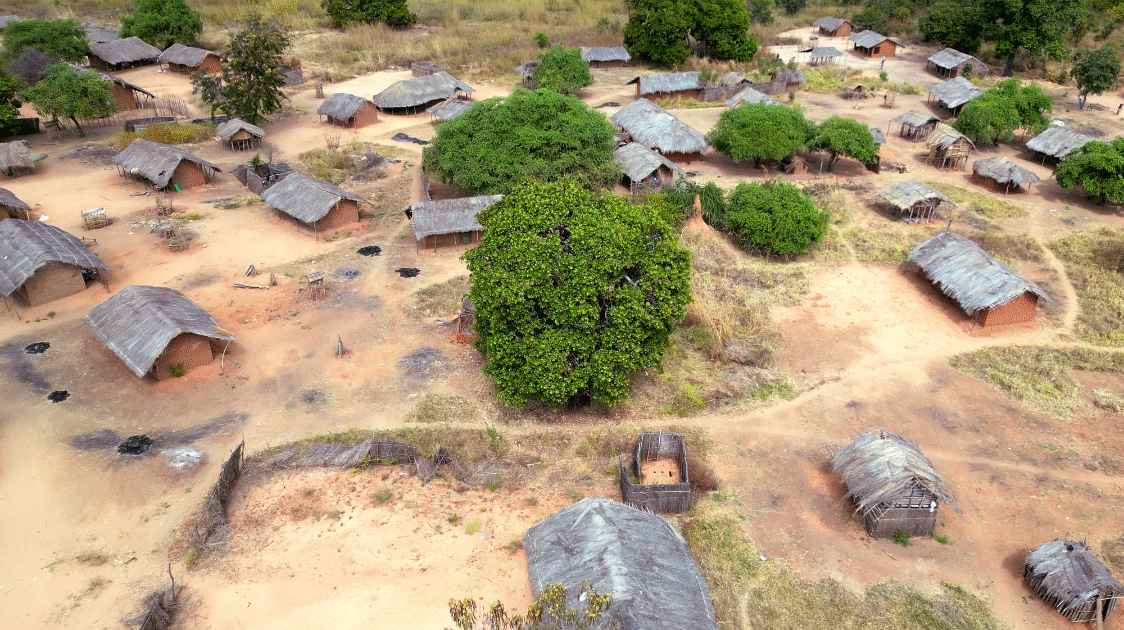

Tanzanian President John Magufuli issued a directive ordering government ministries to “identify conservancies and forest reserves that have no wildlife so that the same are given to landless pastoralists and farmers.”

This effectively formalized the political incentive structure: once hunting concessions collapse economically, and wildlife is depleted through encroachment and poaching, the land becomes available for redistribution to voters.

Without protection, these areas have largely been converted to settlement and pastoralism, with predictable consequences for the habitat and wildlife they once secured.

This abandonment of 75,100 sq km of wilderness (the equivalent of nearly four Kruger National Parks) represents one of the largest single land-use transitions affecting the African environment in history.

The bitter irony is, Tanzania’s government explicitly noted in their formal response to the USFWS was that they had already implemented a six-year age minimum for lion hunting, the very system scientists like Craig Packer had recommended, and harvest rates for lions ranged from 0 to 0.68 harvested lions/1,000km² across the main ecosystems of Tanzania, and were always under the threshold of sustainable harvest.

They argued that their system already met the conservation standards demanded by the USFWS.

Conservation experts who convened in Johannesburg in 2018 to assess the situation described this as potentially the most significant crisis facing conservation on the African continent.

The economic foundation that justified keeping these landscapes as wildlife habitat has eroded, and nothing of comparable scale has replaced it.

Persistent Propaganda

Persistent anti-hunting propaganda suggests that ecotourism can fill the gap left by safari hunting revenue.

Research consistently demonstrates this is not possible across most hunting landscapes.

Lindsey et al. (2006) found that safari hunting clients are willing to hunt in areas with low wildlife density, unattractive scenery, and limited tourism infrastructure.

This is precisely why safari hunting can generate revenue in places that photographic tourism cannot reach.

A Conservation Biology study determined that only 22% of Botswana’s Northern Conservation Zone had intermediate to high potential for photographic tourism, meaning 78% of that land would struggle to support ecotourism operations.

This reality is fundamental.

Ecotourism requires accessible locations, scenic landscapes, high densities of charismatic species, and substantial infrastructure.

Safari hunting requires none of these.

It can operate profitably in remote, marginal areas that would otherwise have no economic justification for wildlife conservation.

Animal rights activist ideology that focuses on individual animals’ rights while ignoring landscape-level outcomes is willful deceit.

The peer-reviewed literature is consistent: banning hunting without viable replacement funding leads to habitat conversion, increased poaching, and deteriorating community-wildlife relations.

Biogeography is non-negotiable. African wildlife needs connected landscapes, and safari hunting concessions provide much of that connectivity.

Any strategy that ignores this reality is working against the ecological foundations on which genuine conservation depends.

Zimbabwean native Zig Mackintosh has been involved in wildlife conservation and filmmaking for 40 years. Over the years, he has traveled to more than 30 countries, documenting various aspects of wildlife conservation. The sustainable use of natural resources as an essential conservation tool is a fundamental theme in the film productions with which he is associated.