How Many Domestic Goat Conservation Conferences Are There?

By Prof Brian Child

Key Takeaways:

- Public ownership of wildlife has become the norm as the rights, capacities, and confidence of local communities to manage forests, wildlife, and fisheries have decayed.

- Public governance is historically dominant but is overstretched and underperforming.

- Regulations are worse than worthless unless they can be enforced and funded.

- The process by which regulations are made is important. It should involve people in regulating their own affairs

- Proprietorship is a foundational concept that underpins land husbandry, free markets, sustainable economic growth, equity, and even inclusive governance.

- We need new institutions for wild species and spaces, with private-community proprietorship and CBNRM being especially important given the overlap between wild species and indigenous and local communities.

Private ownership of many wild resources is sensible, especially if properties are large enough to internalize most of the costs and benefits associated with them.

However, combining private ownership (including community-private) with collective self-regulation is an even better solution because it accounts for both the private and common-pool attributes (i.e., externalities) of these resources.

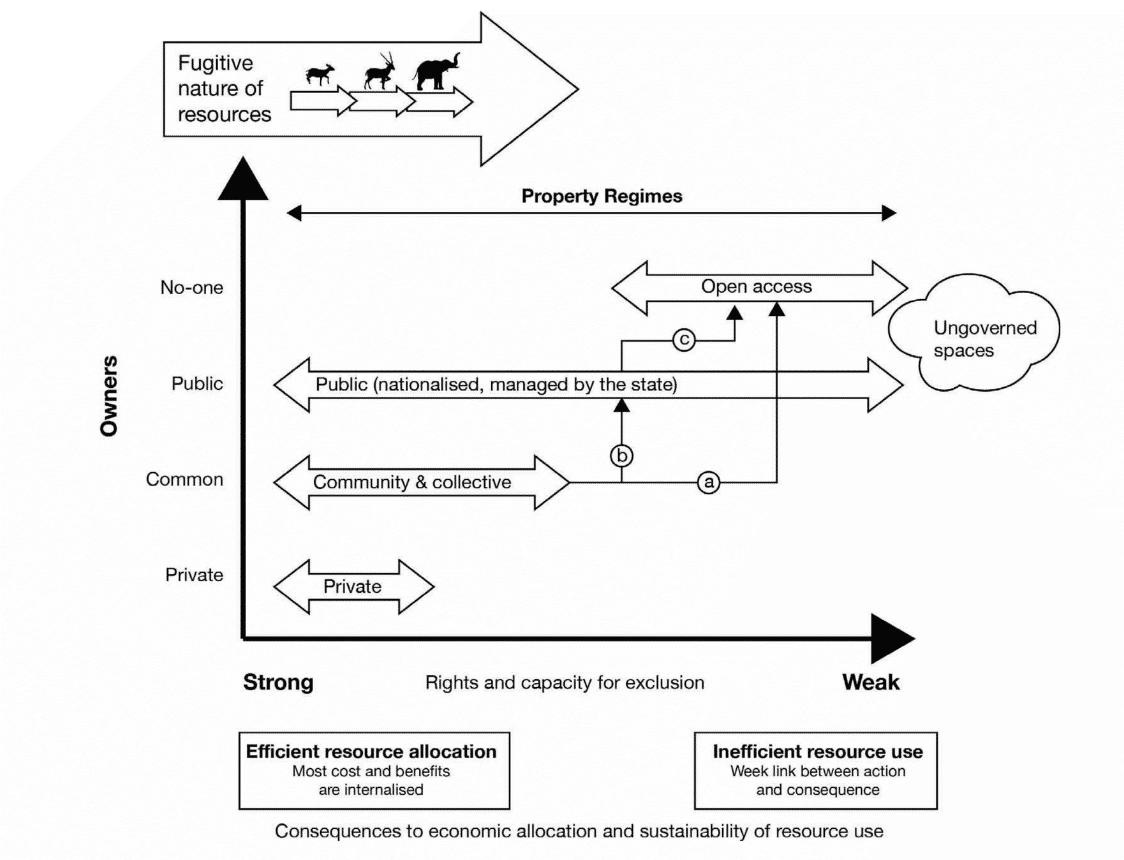

Unfortunately, there has been widespread decay of community property regimes towards an open-access situation (illustrated by arrow ‘a’ in Figure 5.5), as colonial and post-colonial regimes eroded the rights, capacities, and confidence of local communities to manage forests, wildlife, and fisheries.

Wild resources, and especially those owned by communities, were often nationalized (arrow ‘b’), with public ownership becoming the norm. However, many public management regimes have decayed towards open-access regimes and ungoverned spaces (arrow ‘c’), especially when attempting to manage public wild resources on private or community land under modern, global pressures.

In some circumstances, nonetheless, public ownership and management of wild resources is highly effective. National Parks are a good example, provided they are socially legitimate, provide benefits to society, and are capacitated to manage the resources and exclude free riders, poachers, and land encroachment.

Park boundaries, incidentally, are a cost-effective mechanism of exclusion, and can be remarkably effective even with relatively low investments in patrolling and exclusion.

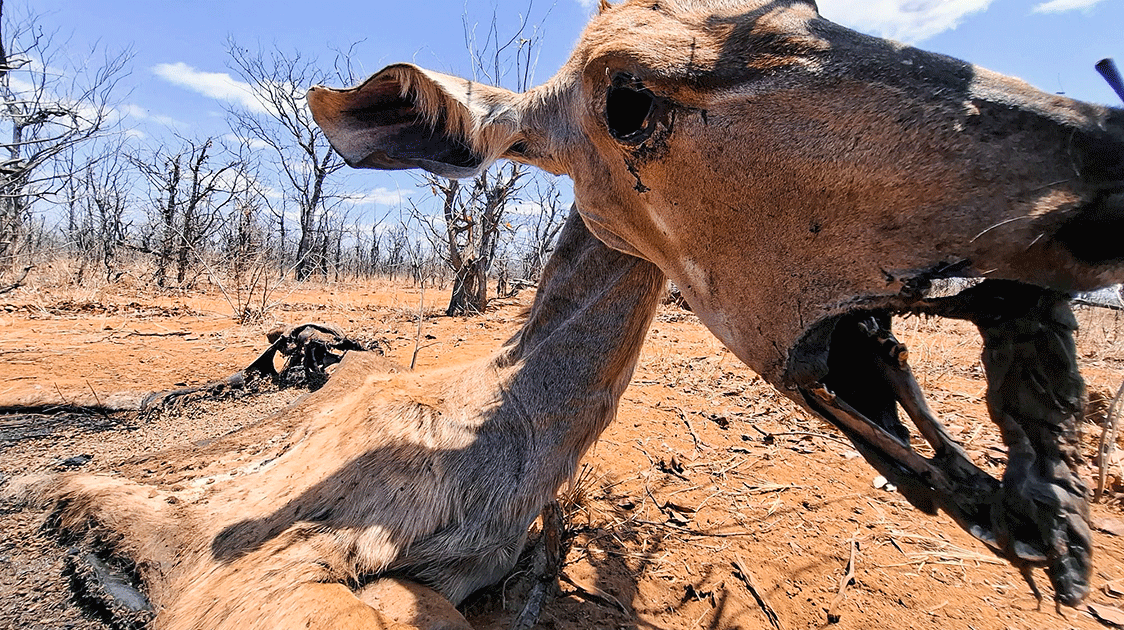

However, when under-resourced or lacking social legitimacy, many parks rapidly become paper parks (arrow ‘c’), unable to exclude illegal hunting or settlement.

In places where states fail to manage the relatively straightforward task of protecting national parks, we should be even less confident in the efficacy of public management of wildlife and biodiversity under much more challenging circumstances outside parks.

Yet this pattern of nationalized wild resources, inadequate state capacity for exclusion, and alienated communities is the norm in post-colonial states in Africa, Latin America, and much of Asia (i.e. arrows a, b, and c), and explains the magnitude of the losses of wild resources.

To reverse the trend towards ungoverned spaces, we need to move to the left of Figure 5.5, where mechanisms for internalization costs and benefits and exclusion are strong, through various combinations of private, community, and public governance.

Public governance is historically dominant but is overstretched and underperforming. This points us towards private and collective forms of management.

Private property regimes are simple to administer and can be very effective. We are most familiar with individual private property – such as farms or, more recently, private wildlife reserves and forests.

However, the vast extent of ungoverned spaces occurs where communities' and biodiversity priorities overlap, suggesting that we have most to gain globally by developing private community resource management and production units – the subject of Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM).

Forms of collective action

Collective action takes several forms, with different purposes and benefits. Ostrom mainly discusses collective self-regulation by the users of a shared resource.

My focus is different.

I am primarily concerned with the internal governance of communities as private-community production units, or Village Companies.

‘Collective management’ refers to the action of bringing villages, or even private ranches, together to manage much larger landscapes (ecologies of scale), or because of economies of scale linked to brands, markets, supply chains, and so on.

Regulations and property rights

Policies, rules, and regulations have a tremendous impact on society's performance, even though they are largely invisible. By affecting property rights and markets, regulations and regulators significantly shape the distribution of costs and benefits and can enhance or retard devolved, market-based approaches.

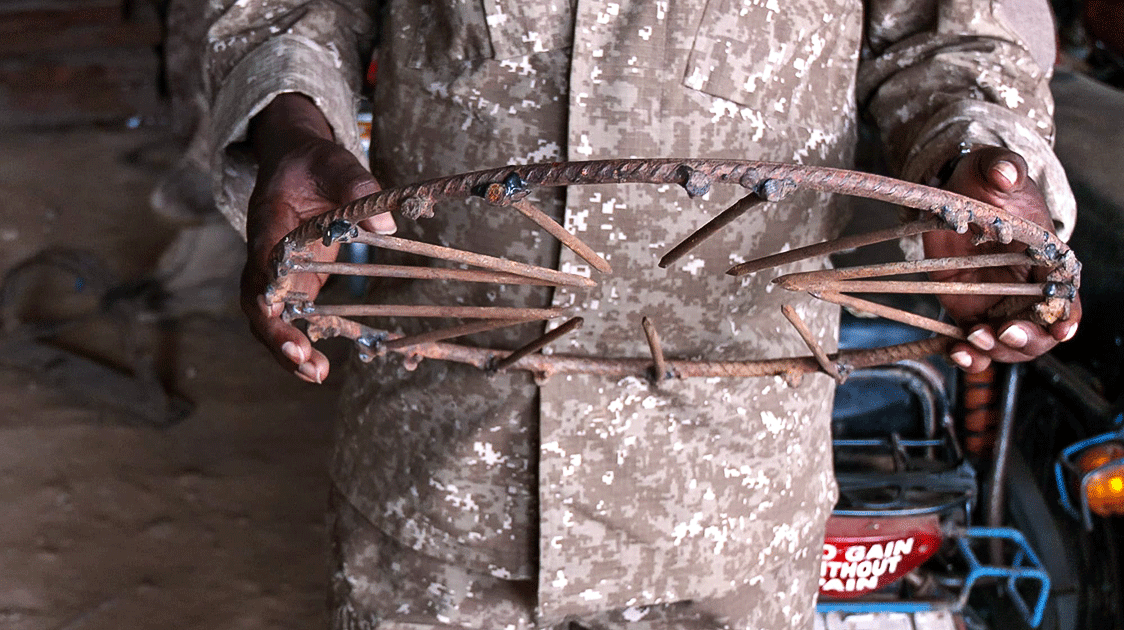

An unfortunate consequence of the highly centralized governance of wild resources is that regulations are also thrown around like confetti (by bureaucrats and at international conventions), with far too little accountability given for the fact that these actions are far from costless.

Wild resources are invariably over-regulated, with little thought as to how regulations move the cost curves or undermine the credibility of the regulatory agency – regulations are worse than worthless unless they can be enforced and funded, and over-dependence on them is undermining this approach.

Legislation, policy, and regulations are best applied sequentially. The first priority of policy and legal reform is to get prices right for wild resources through appropriate combinations of proprietorship and markets.

To shift the profit curves for wild species upwards, we need to reverse historical norms such as public ownership, market closure, and the imposition of transaction costs (e.g. red tape), fees (e.g. licenses), and limitations on management options.

Once the pillars of price and proprietorship are in place, markets and regulations need to be carefully crafted to get the right outcomes.

For example, we might need to design the market for rhino trade to drive landscape conservation and avoid pen-fed rhino production. In places where we are promoting private-community ownership, regulations and mechanisms are necessary to control the standard of devolved governance.

Finally, taking a market-based approach does not mean neglecting regulations for externalities that cannot be controlled through privatization and local self-regulation, or ignoring the need to subsidize valuable biodiversity that cannot finance itself.

The process by which regulations are made is important. It should involve people in regulating their own affairs, and regulations should be parsimonious and as close to the action as possible.

Regulations are also political, with major distributional implications, and we can never ignore the political question of ‘who decides’. Regulations work best in inclusive societies, such as North America, where hunters and recreationists benefit significantly from the public management of wildlife and wild spaces.

CBNRM, public administration, and decentralization

Decentralization

Common property management, including CBNRM, overlaps significantly with the practice and theory of public administration, and especially decentralization.

Decentralization, or the process of redistributing functions and powers away from a centralized authority, has received a lot of attention in recent literature on CBNRM and community conservation (Ribot, 2008; Ribot et al., 2010).

Decentralization is complex and takes several forms (Box 5.2).

Although definitions vary between scholars, I consider ‘deconcentration’ to merely shift central government functions to district-level officials.

‘Delegation’ empowers entities that are independent or semi-independent of government, such as community producer associations or local park management committees. CBNRM is about ‘devolution’, economic, political, and administrative.

BOX 5.2 DEFINING TERMS USED WITH DECENTRALIZATION

Decentralization: the redistribution of functions away from a central locality or authority.

Administrative decentralization:

• Deconcentration: passing the responsibility for regulation or service provision to a central government institution that is located outside the capital (e.g. district administrators, field offices of government agencies);

• Delegation: shifting the regulation or provision of goods from government to public corporations, associations, or publicly regulated private enterprises (e.g. trade unions, farmers associations, regional planning authorities);

• Devolution: empowerment of autonomous and independent local bodies (e.g. local municipalities, indigenous and community forests);

• Privatizations: transferring responsibilities or functions and allowing them to be performed by private businesses;

• Deregulation: the reduction or removal of state regulations, often to free up market allocation of goods. Political decentralization: measures that give citizens more power including democratization and subsidiarity.

Source: adapted from Rondinelli (2003).

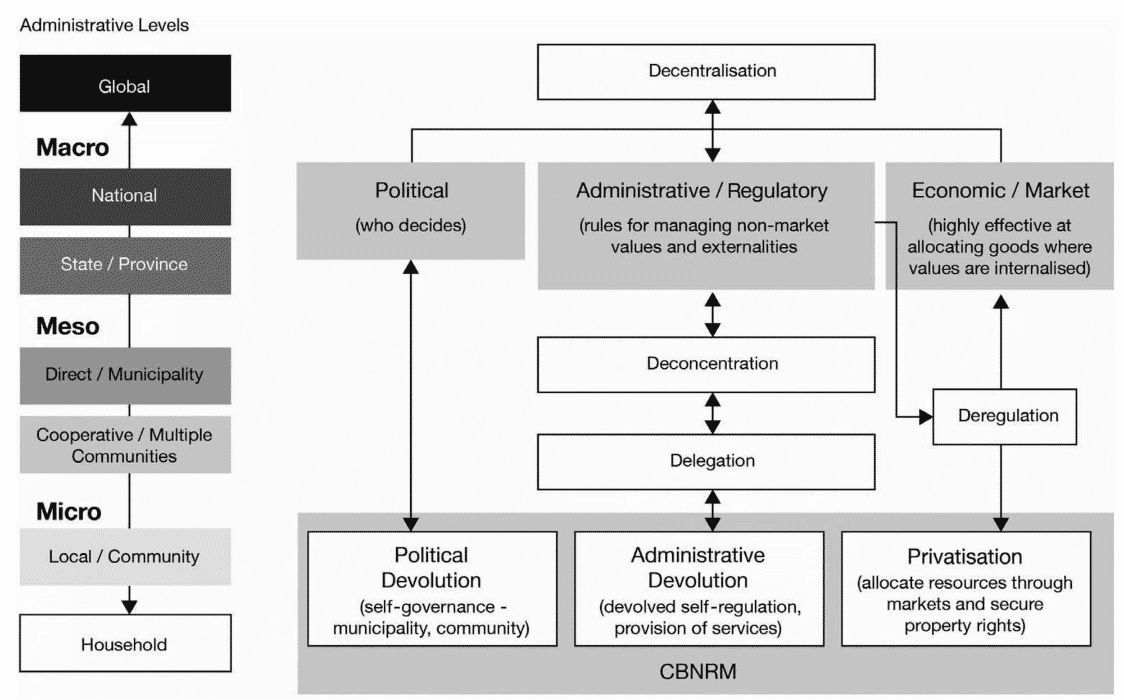

CBNRM often involves three distinct yet simultaneous forms of decentralization (Figure 5.7). Economic decentralization, including privatization and deregulation, is central to CBNRM.

This empowers communities to act as economic production units with the freedom to choose. It shifts the allocation of goods from the centrally planned state to landholders, communities, and markets by devolving rights to access, use, manage, sell, and exclude others from a resource.

In terms of community self-governance, CBNRM also includes elements of political devolution. Administratively, CBNRM communities are empowered to plan and zone natural resource use and are often called upon to provide their own social services using income from wild resources (e.g., building schools, health posts, or providing water), especially where government is remiss and unable to provide these services.

In CBNRM, these distinctions between deconcentration, delegation, and devolution are not always made clear (Ribot et al., 2010).

CBNRM should not be seen as deconcentration, converting community bodies into mini-natural resource agencies (forestry, wildlife, fisheries) focused on regulatory responsibilities rather than production, as sometimes happens when it is confounded with district administration.

Rather, CBNRM is analogous to private natural resource management, except that the production unit is a community rather than an individual.

The economic and political implications of property rights

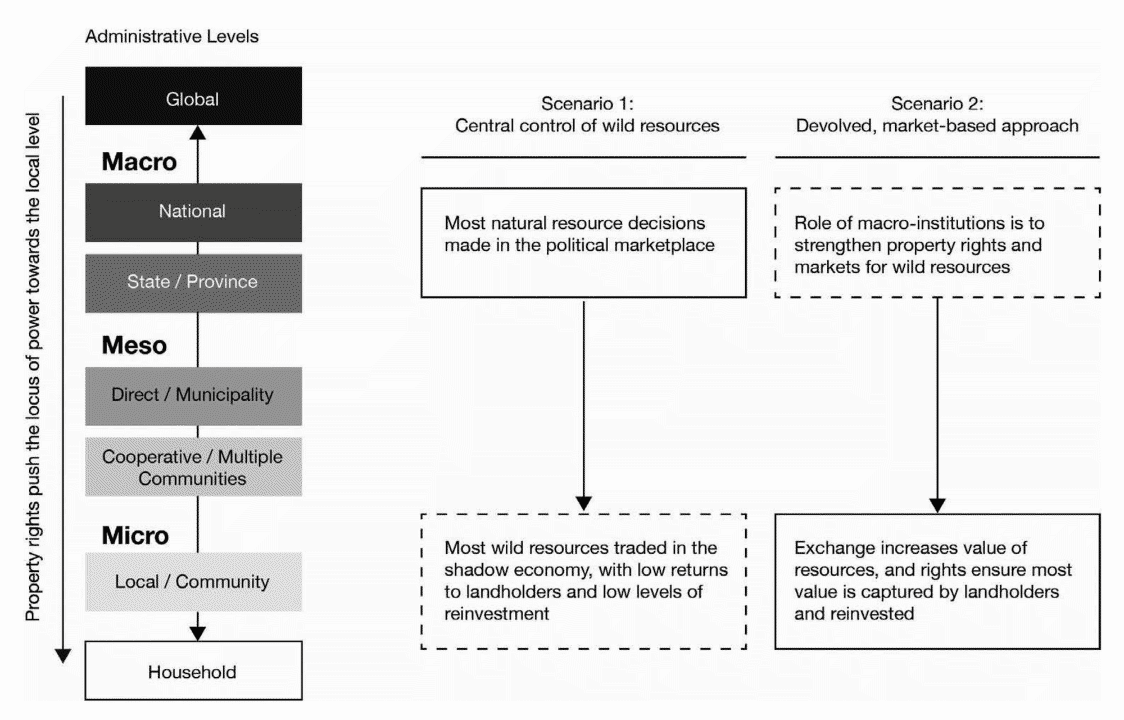

A discussion of tenure is incomplete without highlighting its massive impact on the political economy and governance of wildlife. The locus of property rights determines the function of macro-institutions and their prominence relative to productive activities.

Defining wildlife as a public good means that most decisions are made centrally in the political marketplace (Figure 5.8).

By contrast, property rights shift the locus of power and decision-making to the local level and to the discretionary choices of a market-based system (Barnes & Child, 2014).

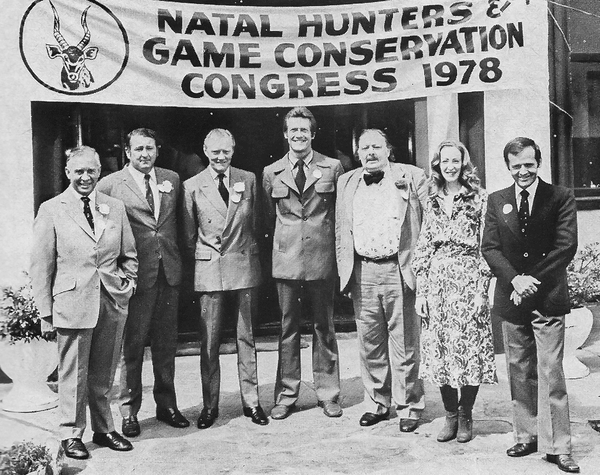

I used the examples of rhinos and the bizarre bazaar that is CITES, to illustrate the weaknesses, dangers, and dysfunctions of the centralized systems in which we (mis)placed so much responsibility.

Indeed, at a global level, they epitomize democratic failure, are leapt upon by special interests (Olsen, 2000), write rules they are unwilling to pay for, and have a near-criminal tendency to impose opportunity costs on others without accountability.

I would go so far as to say that this dysfunction is the central cause of a market failure that prevents many people who are willing and want to pay for environmental goods from dipping into their pockets, because they simply do not trust these mechanisms and the players feeding off it.

But make no mistake, these are still marketplaces where people trade power, treasure, and influence, with limited accountability for performance in measurable conservation or poverty reduction.

This is not to blame the many wonderful and committed people who are doing their best to save the planet, but to highlight how ineffective and frustrated we will all remain unless we evaluate, challenge, and change the system.

Not only is the devolution of rights the right thing to do for community rights and the wildlife economy, but it will also radically alter the political structure of the system, shifting most decisions into the economic marketplace.

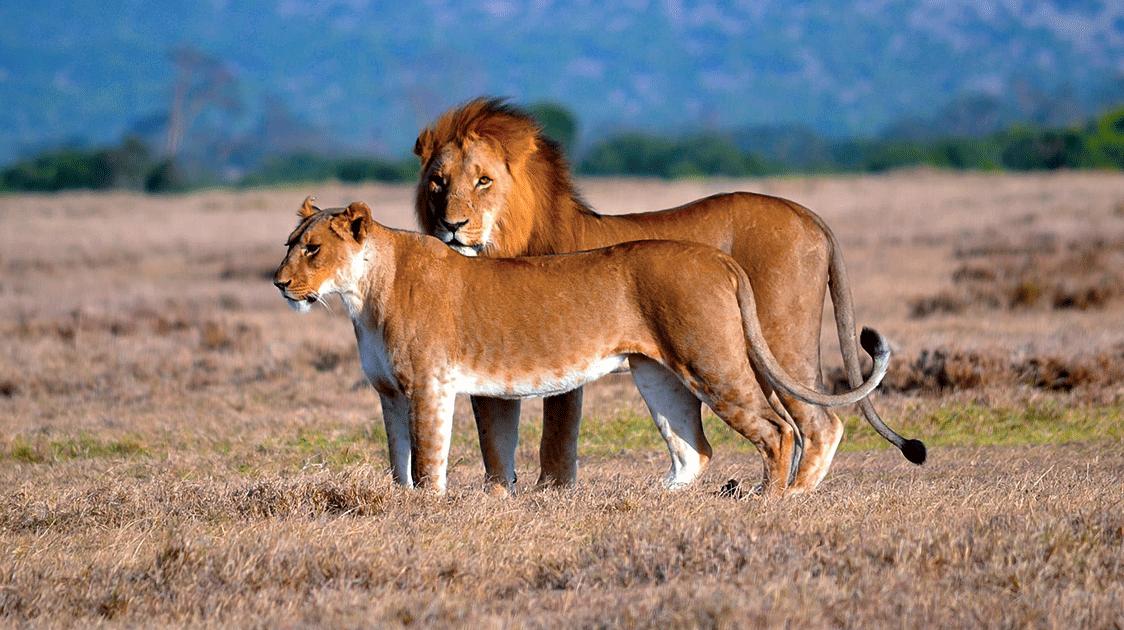

With privately owned livestock, for example, most cattlemen live on the farm, exchange takes place between individual livestock owners in the economic marketplace, and there is no need for international meetings to ‘fix the problem’.

Despite so few international conferences for the conservation of goats or the international trade in cattle, domestic species are increasing rapidly.

By contrast, landholders and communities do not have strong rights over wildlife, and the plethora of global wildlife conferences do not appear to be doing much to stop it from disappearing so quickly.

In a centralized system, exchange blossoms in two places, neither of which results in serious investment in the resource base: the political marketplace of national and global bureaucracy, central financing and philanthropy, and special interests, and the economic shadows where exchange is informal and often criminalized.

The structure of property rights also has significant implications for the distribution of talent.

Skillful farmers stay on the farm, whereas talented conservationists are rewarded for attending meetings and spinning stories that raise money.

One of the tragedies of the current times is the disincentives for dedicated and capable conservationists to work deep in the field where they are most needed, at the coalface of effectiveness and innovation.

Proprietorship is a foundational concept that underpins land husbandry, free markets, sustainable economic growth, equity, and even inclusive governance.

It affects how wildlife politics plays out and even where conservationists work.

After a century of publicly governing wild resources, we need to adapt to the emerging realization that wild species are essentially private goods with common-pool properties, becoming progressively more excludable and subtractable on the crowded planet of the 21st century.

There is an increasing mismatch between the nature of wild resources (private or common-pool resources) and their governance as public goods.

These institutional misalignments create many of the problems faced by wild resources, including replacement by domestic species, over-exploitation, under-investment, and the inequitable distribution of costs (local) and benefits (national or global).

On a crowded planet, public wildlife is unlikely to thrive on private land. Unless we change direction, wild species will be steadily relegated to the 15% of the earth that is public land.

We need to strengthen the world’s protected areas, but outside them, we need new institutions for wild species and spaces, with private-community proprietorship and CBNRM being especially important given the overlap between wild species and indigenous and local communities.

Prof Brian Child is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida and the Life Through Wildlife Project director. His book, “Sustainable Governance of Wildlife and Community-Based Natural Resource Management”, is available on Amazon.