CITES – a Convention for Wildlife Trade Regulation, or for Wildlife Trade Prohibition?

Key Takeaways:

- CITES was set up to regulate the trade in wildlife products, not prohibit it.

- There are 184 country members (Parties) who can vote on issues. Observers (NGOs) cannot vote, but they do influence policies.

- The public at large has come to support a non-use wildlife paradigm, mainly as a result of well-funded campaigns flooding the media, both traditional and social.

- Most sustainable use practices, particularly safari hunting, are forcefully condemned.

- "Crisis in Conservation" is a lucritive rallying call for anti-trade NGOs.

- The anti-trade arguments are easily rebutted.

- Experience with Prohibition (alcohol) and the War on Drugs (narcotics) shows that trade bans do not lower demand.

I am recently back from the 20th CITES Conference of the Parties (CoP) in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. It is the fifth one in a row I have attended since CoP16 in 2013 in Bangkok.

I now have a fairly good understanding of the arcane CITESese language, which consists mostly of acronyms and strange alphanumeric formulations of Decisions, Resolutions, paragraphs, Documents of various sorts, such as Proposals to change a species' Appendix listing, Agenda item documents, Information Documents, and many more.

I have become so attuned to the politics of the forum, attracting around 3,000 participants, that I can, with high probability, predict which side of any trade issue a Party will speak for or against.

It is even easier to predict on which side of an issue an Observer will intervene. NGOs are the primary type of Observer that make spoken interventions, and well-defined battle lines have developed over the years between those who are pro-trade, if sustainable, and those who are anti-trade under any conditions, even if the species numbers in the millions over a wide range.

Yes, there are such species listed under CITES (e.g. Saiga antelope).

CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is an international agreement between governments.

It aims to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten the survival of the species. Countries that have adopted the Convention are termed 'Parties', i.e. a Party to the Convention.

There are currently 184 countries and the European Union bloc as Parties. The EU bloc cannot vote; each of the 27 member countries has one vote. Observers cannot vote.

CITES entered into force on 1 July 1975, so it is celebrating its 50th birthday. But some people ask, what is there to celebrate?

In the 1970s, when IUCN launched the idea for an international wildlife trade Convention, sustainable utilization (SU) of wildlife was a widely held view. IUCN, along with WWF and other conservation organizations, strongly supported the concept.

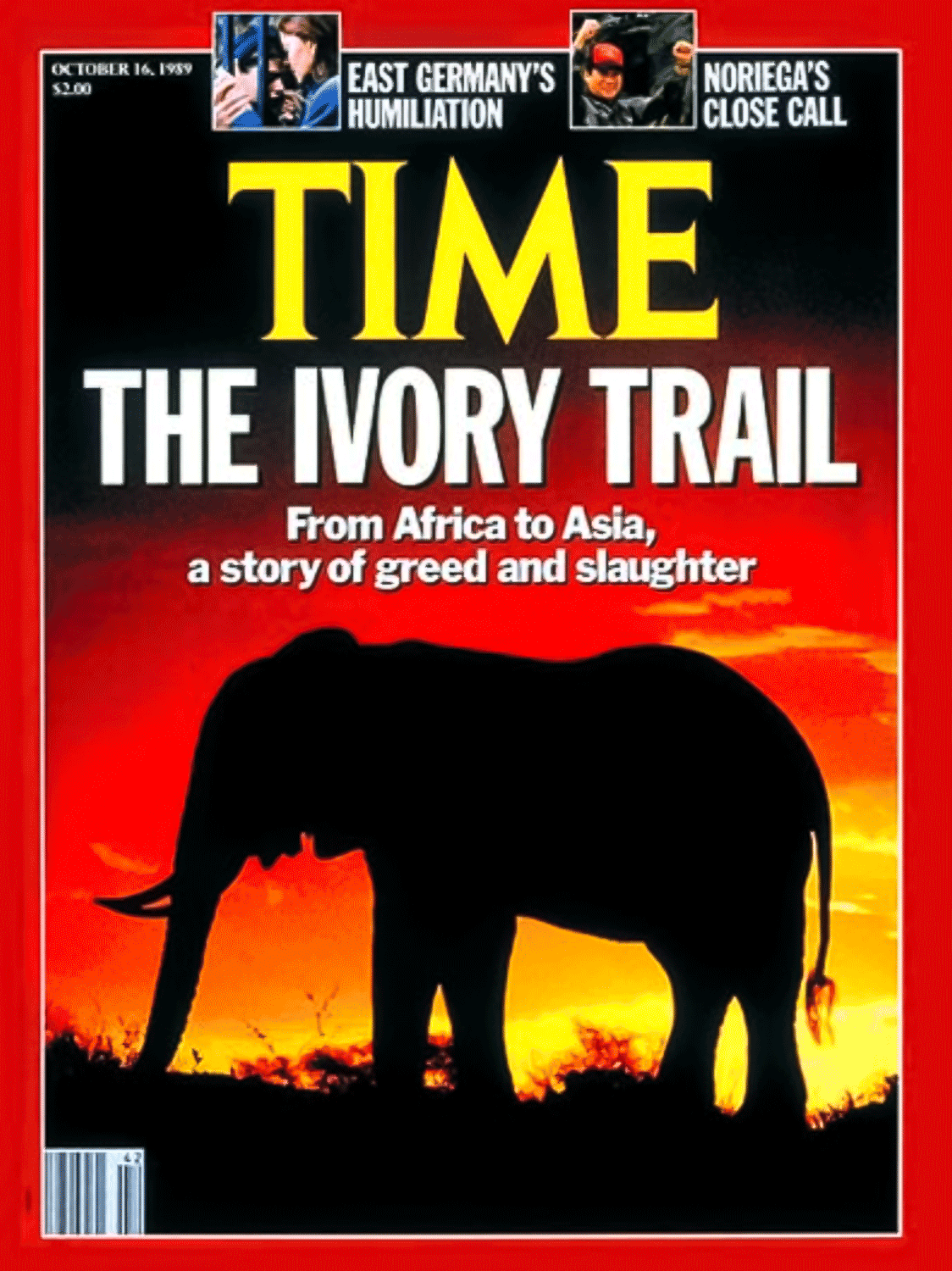

In the 1980s, things began to change, with the concern of widespread poaching of elephants and rhinos increasingly in the media and public eye.

Concurrently, the philosophy of animal rights began to take hold, mainly in the developed North. Several NGOs began adopting its philosophy of non-use of animals, except in a hands-off, observational manner (e.g., photo tourism).

In the wildlife field, Born Free, Save the Elephants, Humane Society International, Humane Society U.S., IFAW, Environmental Investigation Agency and eventually even the Wildlife Conservation Society began to campaign from an animal rights, non-use perspective.

There are now hundreds of NGOs, national and international, operating under this banner, even if they do not explicitly say so.

The public at large has come to support a non-use wildlife paradigm, mainly as a result of well-funded campaigns flooding the media, both traditional and social. Most sustainable use practices, particularly safari hunting, are forcefully condemned.

Almost 41,000 plant and animal species are now listed in CITES Appendices. The species covered by CITES are listed in three Appendices, according to the degree of protection they are assessed to need. Appendix I includes species supposedly threatened with extinction. Trade in specimens of these species is permitted only in exceptional circumstances.

Appendix II includes species not necessarily threatened with extinction, but for which trade must be controlled to avoid utilization incompatible with their survival. Appendix III contains species protected in at least one country that has asked other CITES Parties for assistance in controlling trade.

Changes to Appendix III follow a distinct procedure different from changes to Appendices I and II, as each Party is entitled to make unilateral amendments to it.

Different permitting regulations apply to the Appendices; Appendix I is the strictest, requiring both an import and an export permit in most cases. The rules are pretty complex, and more details can be found here.

The Battle Lines

Since the 1980s, the pro- and anti-trade NGO battles have focused on elephants (mainly ivory) and rhinos (mainly the horn), although in recent years a wide variety of species, both plant and animal, have entered the fray.

The first great success of the anti-trade grouping came in 1989, when African elephants were uplisted from Appendix II to Appendix I and international trade in ivory was prohibited, with a few exceptions (e.g., antiques, pre-Convention ivory, trophy tusks, personal effects).

There were numerous NGO-funded or inspired campaigns (with media such as National Geographic, The New York Times, Time Magazine, etc.).

Encouraged by this success, and realizing that the public and various donor sources were willing to contribute large sums of money to "save the …. (insert flavour of the month species)", many NGOs began building large Communications (i.e. PR) divisions.

A great deal of the funds they received were (and are today) spent on campaigning and creating the impression of a "crisis" in conservation and the threat of imminent extinction, unless funds were received to carry out work to "save" the species at the centre of the campaign.

This approach spills over into CITES conferences.

The anti-trade NGOs' primary objective is to list as many species as possible in Appendix I, or failing that, at least in Appendix II.

Various species of sharks and rays are examples. At CoP18 in Geneva in 2019, anti-trade NGO members dressed as sharks, held side events, and campaigned around the venue, urging everyone to support the listing of Mako sharks and others in Appendix II.

The NGOs were successful, even though the scientific data did not appear to justify the listing.

The opposite is the case when a Party successfully downlists a species or fails to list a species, as occurred at the recent CoP20.

A well-known anti-trade NGO's newsletter reported:

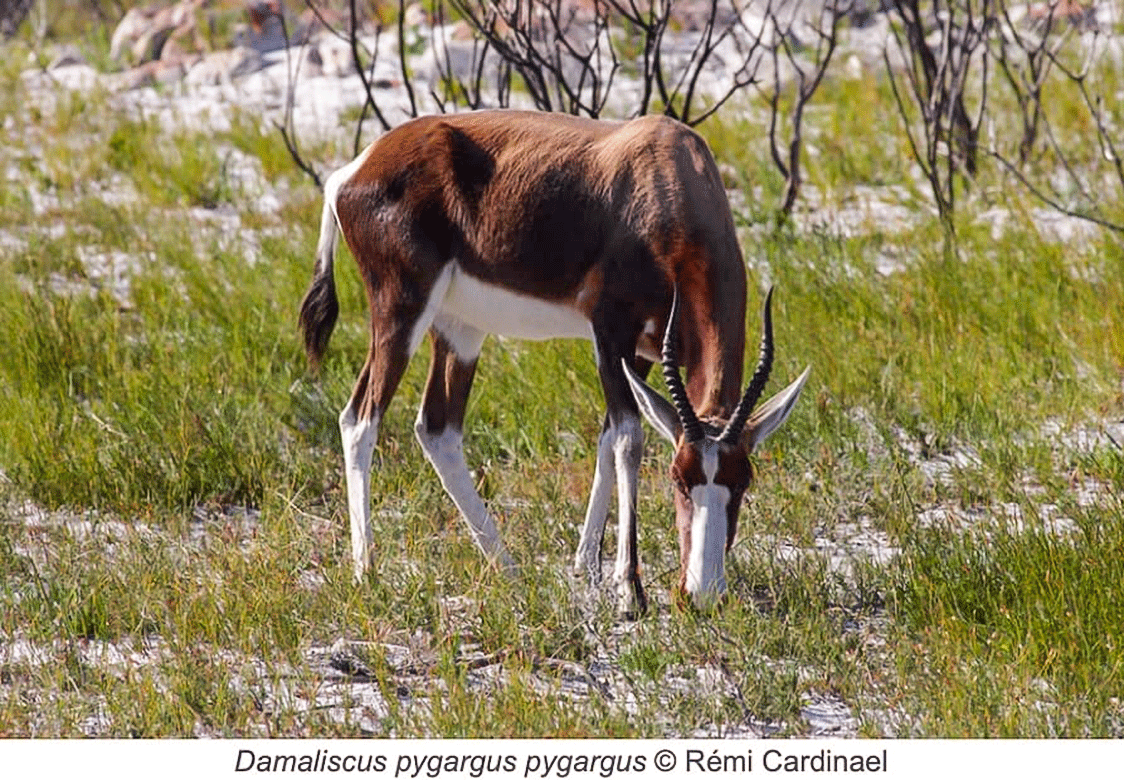

"Three pieces of bad news. South Africa obtained consensus for the removal of bontebok antelopes (Damaliscus pygargus pygargus) from Appendix II.

Only 10,000 specimens remain, a population that the international community considers sufficient for the global trade in its trophies to resume without restriction.

A hunting permit for a bontebok antelope costs around 2,000 US$. It is an attraction for foreign sport hunters."

The newsletter went on to lament the failure to list various rattlesnake and tarantula species in Appendix II.

However, numerous anti-trade NGOs celebrated the defeat once again of a southern African Party's proposals to trade in ivory and rhino horn.

Similar proposals by various southern African Parties have repeatedly been defeated since 2007, when a "one-off" ivory sale of about 105 tonnes of ivory from Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe to China and Japan was approved at CoP14 in The Hague.

This was the last CITES-approved ivory trade. CITES has never approved a proposal to sell rhino horn, in spite of the fact that all of the horn in the sale stockpiles has consisted of horns harvested from live rhinos.

EIA Arguments Against a Legal Ivory Trade

Despite overwhelming evidence that legal trade in rhino horn and ivory fuels demand and poaching, Namibia has submitted three proposals to allow international commercial trade in rhino horn and ivory derived from its populations of white rhinos, black rhinos, and savanna elephants.

If adopted, these proposals could:

- trigger increased rhino and elephant poaching across Africa and Asia

- undermine global efforts to reduce demand for these products, including through the closure of domestic ivory and rhino horn markets

- reverse gains in the recovery of some elephant and rhino populations

- empower criminal trafficking networks already deeply entrenched in the trade.

We have seen this before. The one-off ivory sale of 2008 ignited a poaching crisis that cost the lives of tens of thousands of elephants. The world cannot afford to repeat that mistake.

The Anti-Trade Arguments and Rebuttals

The anti-trade argument depends on six premises. The arguments go like this:

1. Legal ivory trade can be used to "launder" illegal ivory.

2. Corruption is so widespread that no system of legal trade could ever work.

3. Legal ivory trade stimulates poaching, as demonstrated by the two "one-off" ivory sales from southern Africa in 1999 and 2008.

4. The ivory market is so huge that there are not enough elephants in Africa to supply demand.

5. Banning all ivory trade will collapse consumer demand.

6. Destroying all ivory stockpiles sends a message that poaching will not be tolerated. It makes seized illegal ivory impossible to leak into the market, and it devalues ivory, lowering consumer demand.

Let's examine each.

1. Laundering – The only locations where ivory could be laundered are outlets where legal ivory is sold. A foolproof way to constrain the possibility of laundering is to restrict the number of legal outlets and the types of ivory that can be sold.

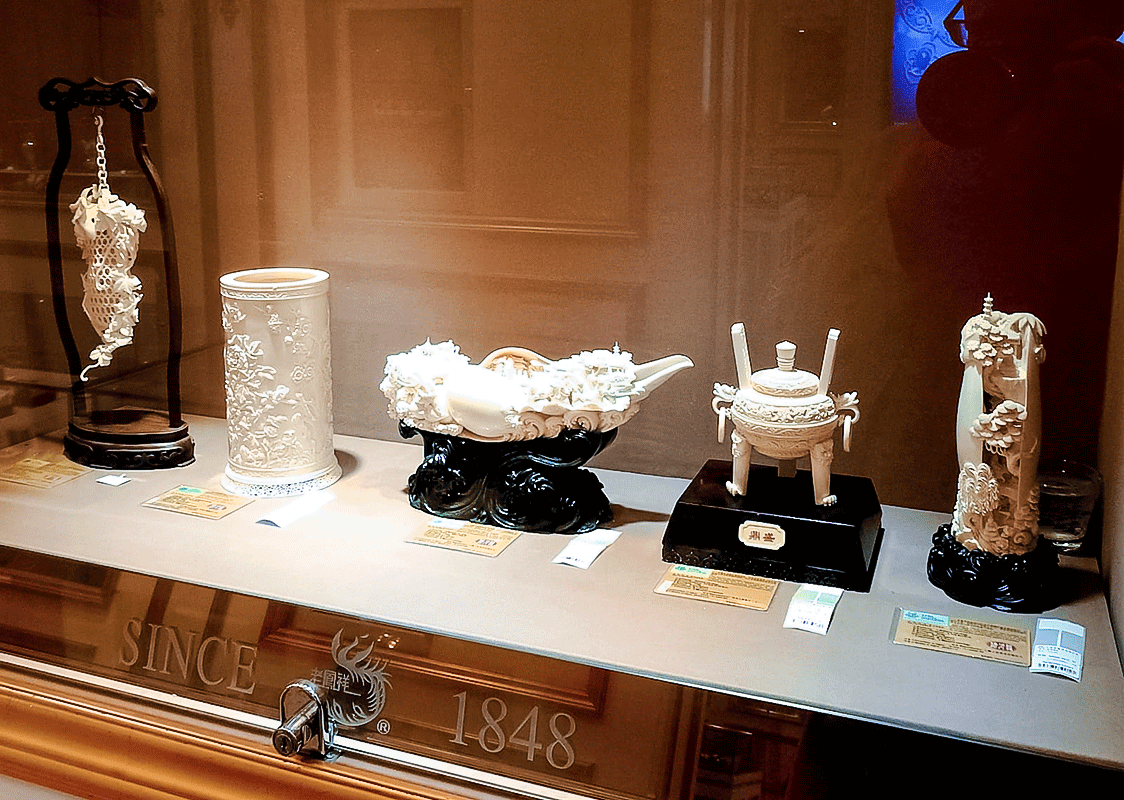

This is what China did when it initiated its legal system in 2004. At the peak of China's legal domestic ivory trade in 2014, there were 37 legal factories and 145 legal ivory outlets in the entire country.

A relatively tiny amount of illegal ivory could be mixed in with the legal ivory in these facilities and laundered.

It was estimated that over 80 per cent of poached ivory was sold in illegal physical outlets, online and through personal networks in China alone, climbing to over 90 per cent of the total market if countries bordering China were included – no laundering was involved in these because there was no legal ivory to mix it with.

Closing the legal outlets and factories in China at the end of 2017 simply drove buyers into the black market system. Now 100 per cent of the market is illegal. Is that a victory for elephants?

2. Corruption – The corrupt trade seen today developed under an international trade ban regime beginning in the mid-1990s, caused by the 1990 CITES ban. This created the corrupt system we see today.

The African countries with the most corrupt ivory trade already have trade bans in place.

So banning trade in more countries is not the solution.

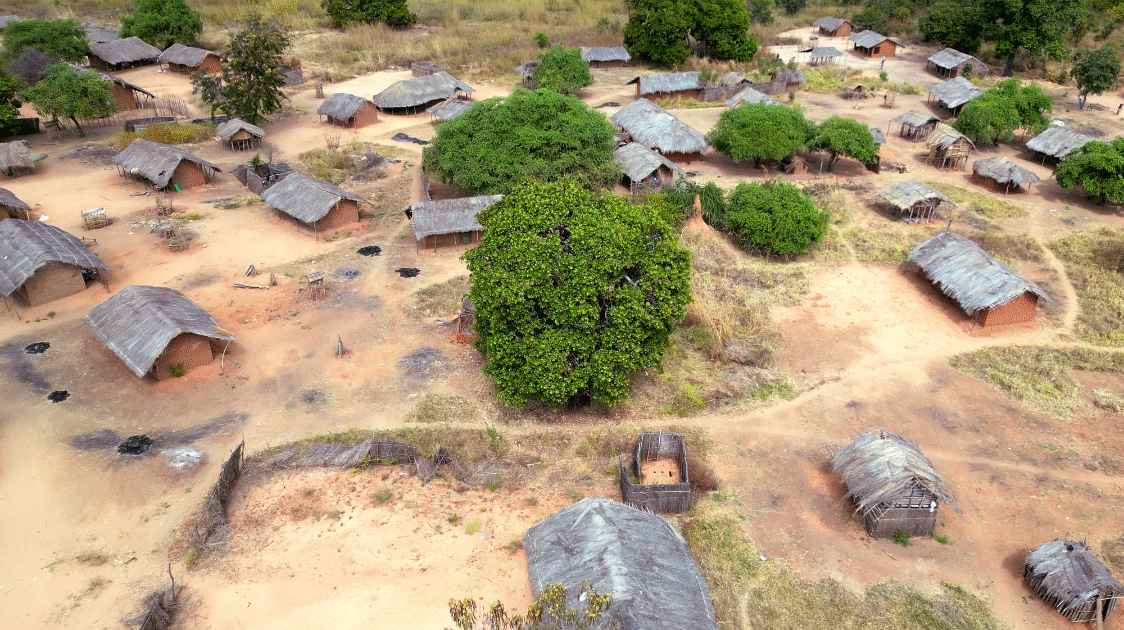

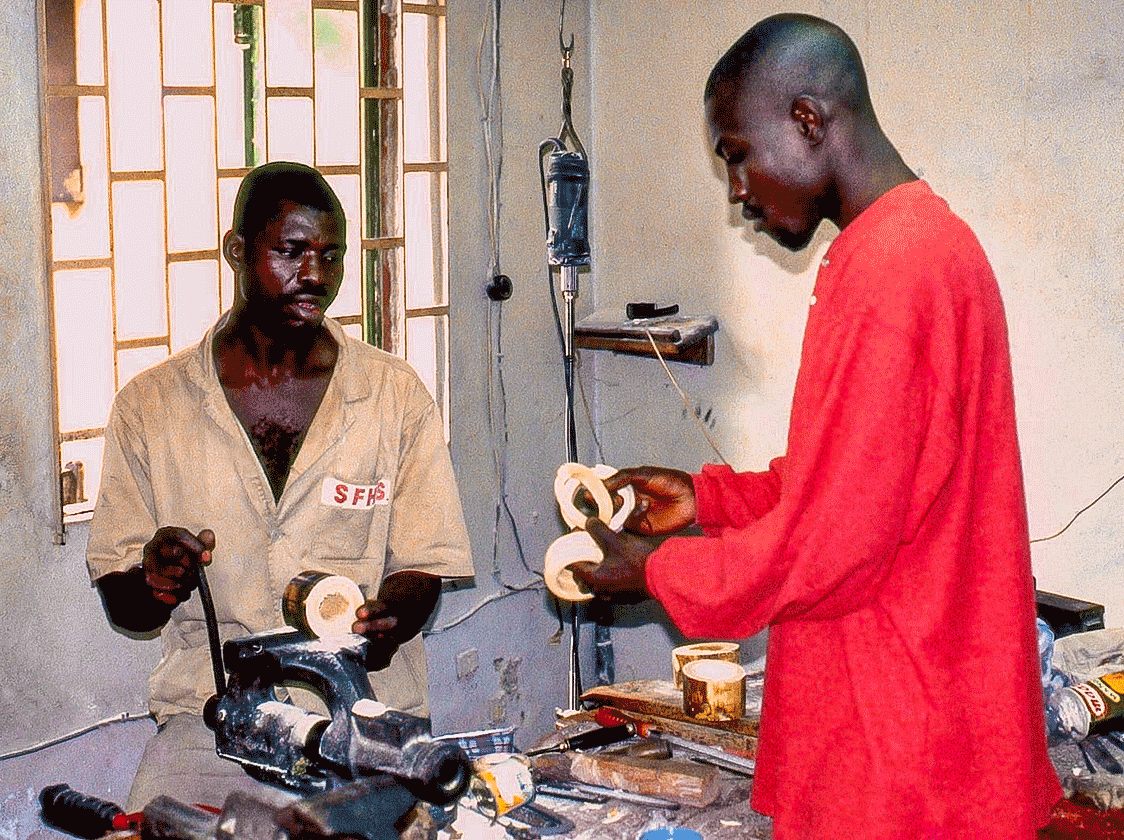

The solution involves bringing African governments into a transparent, regulated legal trade that confers benefits on rural people who live with wildlife and legal tax revenues to governments.

Poor people are the foot soldiers of poaching.

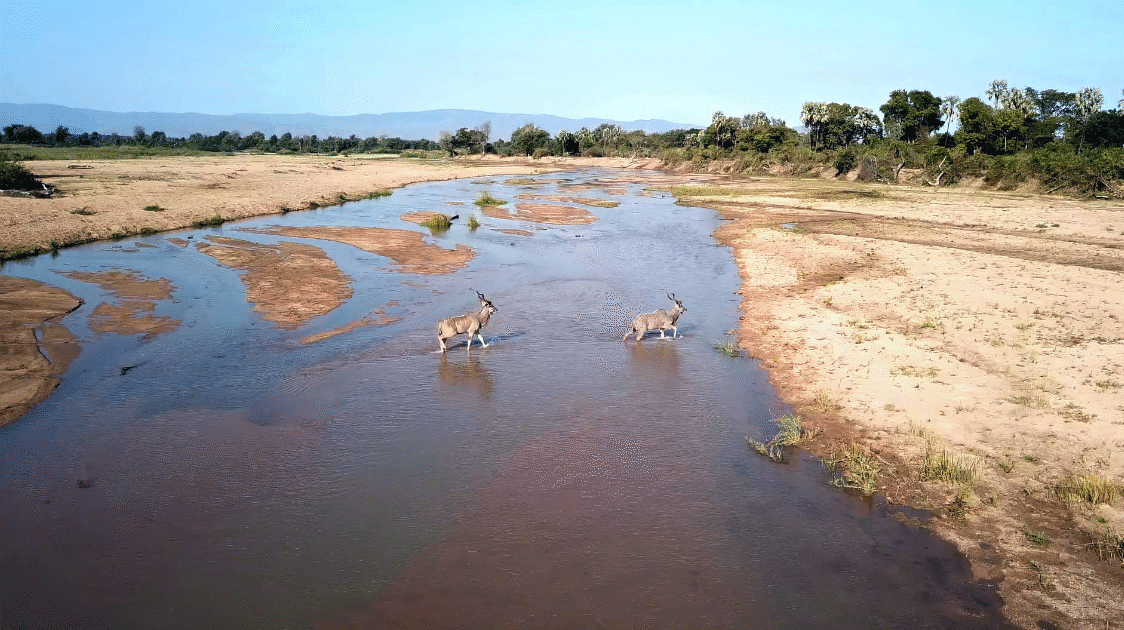

If ivory and other wildlife products could be legally and meaningfully incorporated into their livelihoods, they would be motivated to manage wildlife sustainably for the future.

I advocate a system that provides incentives to obey the law, not the prohibitionist approach, which incentivizes breaking the law.

3. Legal ivory trade stimulates poaching – The assumption is that legal trade stimulates demand, which in turn causes increased poaching to supply that demand. The 1999 and 2008 legal ivory sales did not stimulate poaching, regardless of what some economists say.

Demand in Japan, the only country to receive the 1999 ivory, actually dropped after the sales, and it continued to fall after the 2008 sales.

Ivory demand in China began to rise in 2005, after the government designated ivory carving as intangible cultural heritage and launched initiatives to promote it.

Interest in ivory took off in 2009 during the global financial crisis, as it became an investment vehicle alongside other luxury commodities.

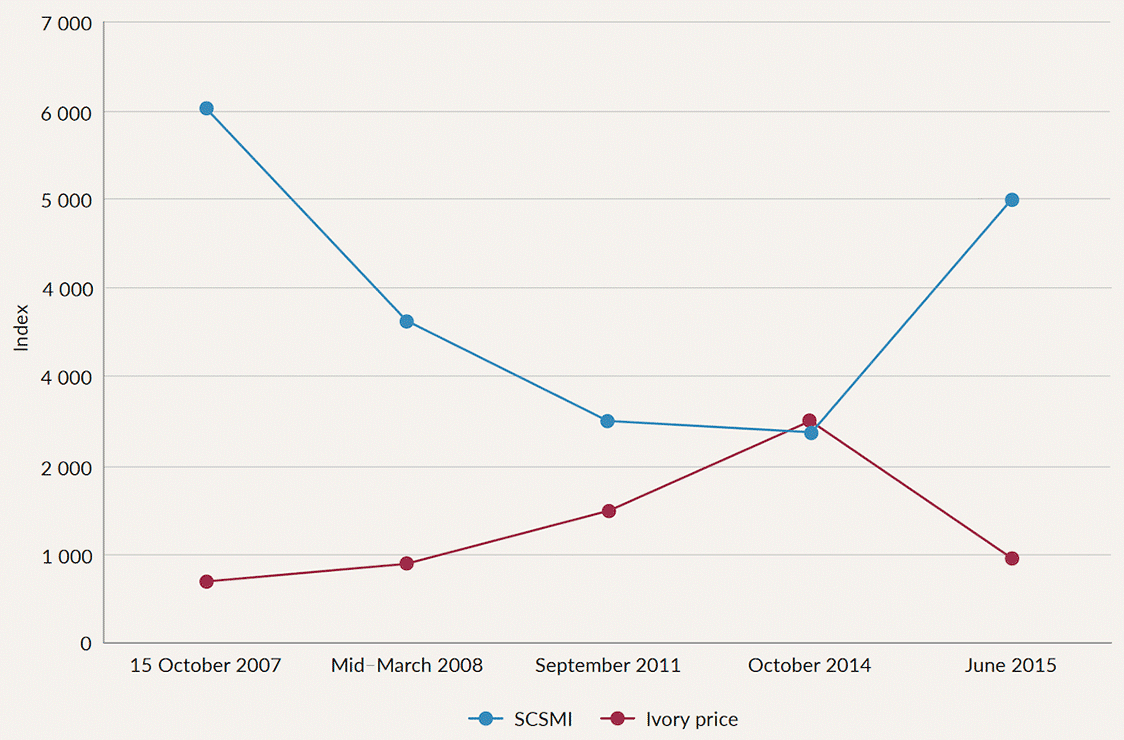

Concurrently, the CITES vote in 2007 to prohibit future legal sales of raw ivory for at least 9 years caused the price of ivory to spiral upward.

Speculators began stockpiling ivory, mostly acquired illegally, expecting prices to continue to rise due to the moratorium's guaranteed scarcity.

Black-market ivory prices in China then spiked from $560- $ 750 per kilogram in 2006 to $2,100 per kilogram in 2014.

This tripling in price contributed to the elephant-poaching crisis. The 2008 legal sale, if anything, kept the price from going even higher.

It was not consumer demand for worked ivory that increased; it was speculator demand for raw and antique ivory for investment that spiked, caused by the global financial crisis.

The vast majority of Chinese consumers did not even know that CITES ivory sales had occurred in 2008, so how could the sales have stimulated demand? Most of the Chinese black market consists of inexpensive jewellery, seals, chopsticks, and trinkets.

Once the financial crisis was over in 2014, Chinese investors dumped ivory and reinvested in the stock market.

4. Not enough elephants to satisfy demand – One of the biggest misunderstandings is the ivory supply and demand.

It does not matter how many consumers want to buy ivory, any more than it matters how many people want a Ferrari.

What matters is how many who want it can afford to buy the commodity.

If one really wants to lower consumer demand, it is imperative that mainly very expensive ivory items are manufactured.

Produce mainly Ferrari-worked ivory pieces; put as few Kias as possible on the market.

This policy cannot be implemented in the presence of an uncontrolled black market under a no-legal-trade regime.

Researchers have shown that the illegal sector in China served the cheaper end of the market, which was much larger than the more expensive legal sector, until the 2018 China market closure.

Ivory is now supplied 100 per cent by poached tusks, with virtually no new art-quality pieces being manufactured.

It is the high demand for cheaper worked ivory (jewellery, signature seals, trinkets) that almost anyone can afford that drives poaching.

Closing the legal market did not make the black market disappear; it simply drove more consumers online and spurred growth in the ivory market in parts of Southeast Asia where law enforcement is lax.

People opposing the ivory trade seem to ignore the fact that elephants die naturally.

It is wasteful not to use the resource, particularly in economically deprived areas. A study concluded that elephant poaching rates are highest in the poorest regions.

There are more than enough elephants to supply a legal market from stockpiles, natural mortality and problem animal control without illegally killing a single elephant – if the ivory items are kept expensive.

In addition, if elephant user-rights ('ownership') are devolved from African governments to local communities, legal ivory income derived from natural mortality and standard problem animal control will fund conservation of wildlife habitats and create the conditions to increase elephant populations.

No elephants need to be killed for ivory.

Keeping the CITES and domestic trade bans in place is resulting in humans replacing wildlife, including elephants, as there is no incentive to keep wildlife on the land, except in exceptionally favoured photo-tourism landscapes.

Even designated protected areas, such as Kenya's Tsavo East and West National Parks, are regularly invaded by livestock and herders.

Elephants are now poached to supply ivory to rogue workshops in East Asia, which manufacture small, cheap items.

This can be countered in two ways: (1) African workshops can provide these items legally, as they do currently in places illegally, and (2) there is always carving 'waste' from working the expensive pieces; some types of the cheaper items (e.g. beads, pendants) can be made from this waste in China.

Supporting African ivory carvers in certain range states under regulated conditions can further incentivise communities to grow elephant populations.

To undercut rogue workshops producing cheap trinkets with poached ivory in Asia, African workshops can produce and export them.

They currently do this in the black market, by bringing them into the legal market with a legal ivory supply, poaching can be reduced while creating employment.

5. Bans reduce demand – Supporters of this assertion often cite the drop in elephant poaching and ivory prices that followed immediately upon the 1989 CITES ivory trade ban – "The ban caused ivory demand and prices to plummet. Resuming trade now will put elephants at even greater risk." – EPI.

But after the huge stockpiles Hong Kong and Japan had accumulated before the 1989 ban began to run low, poaching and prices began to rise again.

The desired results were temporary.

In a 2007 IFAW consumer survey in China, only 7.7 per cent of ivory consumers had bought ivory from registered legal outlets; 75.4 per cent said they preferred to buy it more cheaply illegally.

A 2018 USAID-funded consumer survey in China found that only 44% of respondents were aware of the prohibition on ivory trade.

Despite massive publicity in the West and demand-reduction campaigns in China, 56% of Chinese consumers were still ignorant that ivory was illegal to buy.

Experience with Prohibition (alcohol) and the War on Drugs (narcotics) should be enough to persuade any objective person that trade bans do not lower demand.

Every time calls are made in the U.S. to restrict gun sales further (usually after a mass shooting), gun sales spike upwards.

6. Destroying stockpiles – The first ivory destruction event famously took place in Kenya in July 1989, when 12 tonnes went up in flames to draw attention to the CITES ivory trade ban vote coming up in October in Lausanne.

Since then, by my count, there have been 48 more, totalling at least 301.2 tonnes destroyed.

There was a gap from 1992 to July 2011, when in Kenya, about 5 tonnes were burned. But what message was being sent?

Kenya repeated in 2015 with 15 tonnes and in 2016 with a mammoth 105 tonnes.

The intended message was probably not received by the end-use traffickers; however, they interpret the destruction events as signalling increased ivory scarcity, which means higher prices for them and a motivation to continue buying poached tusks.

Those advocating for ivory destruction have no skin in the game; they are playing with other people's resources.

If they want to destroy ivory, let them pay for it.

I believe the ulterior motive in promoting stockpile destruction is to lower the likelihood of legal trade by reducing potential supply.

Those organizations that promote ivory stockpile destruction and assist in organizing it should pay governments the market value for the ivory.

They would then realize its value. The proceeds could be used to fund community conservation and development initiatives in elephant habitats.

I believe that the prohibitionist ivory-trade policy has led to the elephant-poaching crisis and the deaths of hundreds of thousands of elephants since 1990, when the CITES ivory trade ban came into effect in most countries.

It could have been avoided with a legal system for the supply of raw ivory to China. It may be too late to begin one, unless China reopens its domestic ivory market.

An ivory trade system should be designed to provide long-term, regular supplies from accredited suppliers to accredited buyers.

A 'one-off' sale of the type that CITES authorized previously is NOT recommended.

That is not trade in the usual sense of the term; it is akin to Ford Motor Company selling a lot of 100,000 cars every ten years, but none in between.

The two previous sales created confusion, market instability and an opportunity for wildlife anti-use organizations to manufacture propaganda.

A long-term ivory trade system involving both the producers and buyers has never been tried.

It is way past time to get serious about conserving elephants by satisfying all stakeholders and removing incentives to poach.

The only losers would be the organizations and individuals who receive donations from supporters to stop the "poaching crisis".