Whose Rhino is it Anyway? Accounts and Accountability

By Prof Brian Child

Key Takeaways:

- Wildlife has been miscast as a public good.

- The governance regimes for wild resources no longer match their economic characteristics.

- Treating wild species as public goods results in an inequitable allocation of costs and benefits.

- Benefits are global, but costs are local.

- Rhino owners believe that CITES has infringed upon their property rights to rhinos without compensation.

- The special interest groups that overrule the legitimacies of rhino producers bear no personal accountability.

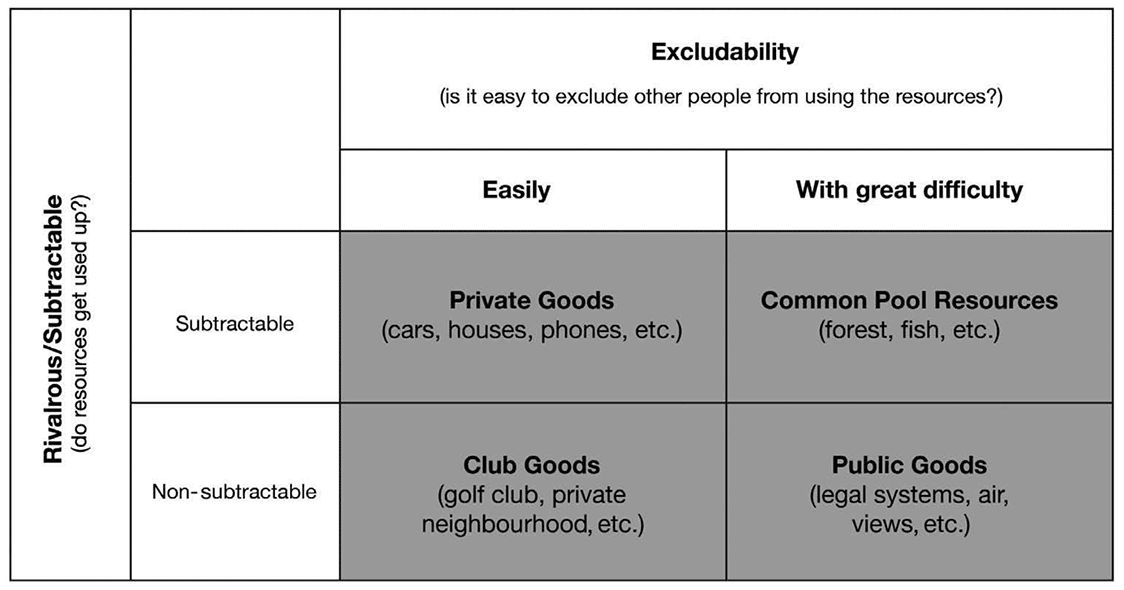

Defining public, private, and common-pool resources, Randall (1983), Polski and Ostrom (1999), and others provided conceptual clarity to the definition of public, private, and common goods by introducing and defining the concepts of ‘exclusion’ and the awkward term ‘subtractability’ (which has a second, equally unattractive, label, ‘non-rivalry’).

‘Excludability’ is the extent to which people can be excluded (or not) from using a resource through physical barriers, technical means, or legal instruments.

High excludability implies that consumers will have difficulty consuming the good or service without contributing to its cost; low excludability means that consumers may be able to ‘free-ride’, consuming the good or service without contributing to the cost of provision or production.

‘Subtractability’ is the extent to which the use of a resource by one person reduces the supply to others. High subtractability implies individual consumption; low subtractability means that more than one person can consume the good or service simultaneously.

Thus, an impala is subtractable because hunting one impala means fewer are available for other hunters, whereas viewing mountain scenery does not subtract from its availability for other people, who are therefore not rivals in its use.

This provides the well-known framework for classifying goods (Figure 1.1) according to whether they get used up or not (i.e. are subtractable or rivalrous) and whether it is easy to exclude others from taking the resource.

Economic efficiency is achieved only for private goods in competitive markets – all other goods are subject to market failure in some way.

Pure private goods are excludable (i.e. their owners can exert private property rights, preventing others from using them without paying for them) and subtractable because consumption by one person prevents consumption by another.

Free markets allocate private goods well. Clubs’ goods are similar, except that they come in large lumps (e.g. golf clubs).

Public goods, by contrast, are non-rivalrous (use by one person of a legal system does not prevent use by someone else) and non-excludable (it is not possible to exclude people from fresh air or street lighting).

Common-pool resources fall in the middle. They are, to some extent, subtractable and can be over-exploited, and it is difficult (but not impossible) to exclude potential beneficiaries from using them.

The combination of high subtractability and low excludability often leads to overuse or under-supply, for example, through overfishing or under-investment in managing the fishery.

The miscasting of wildlife as a public good

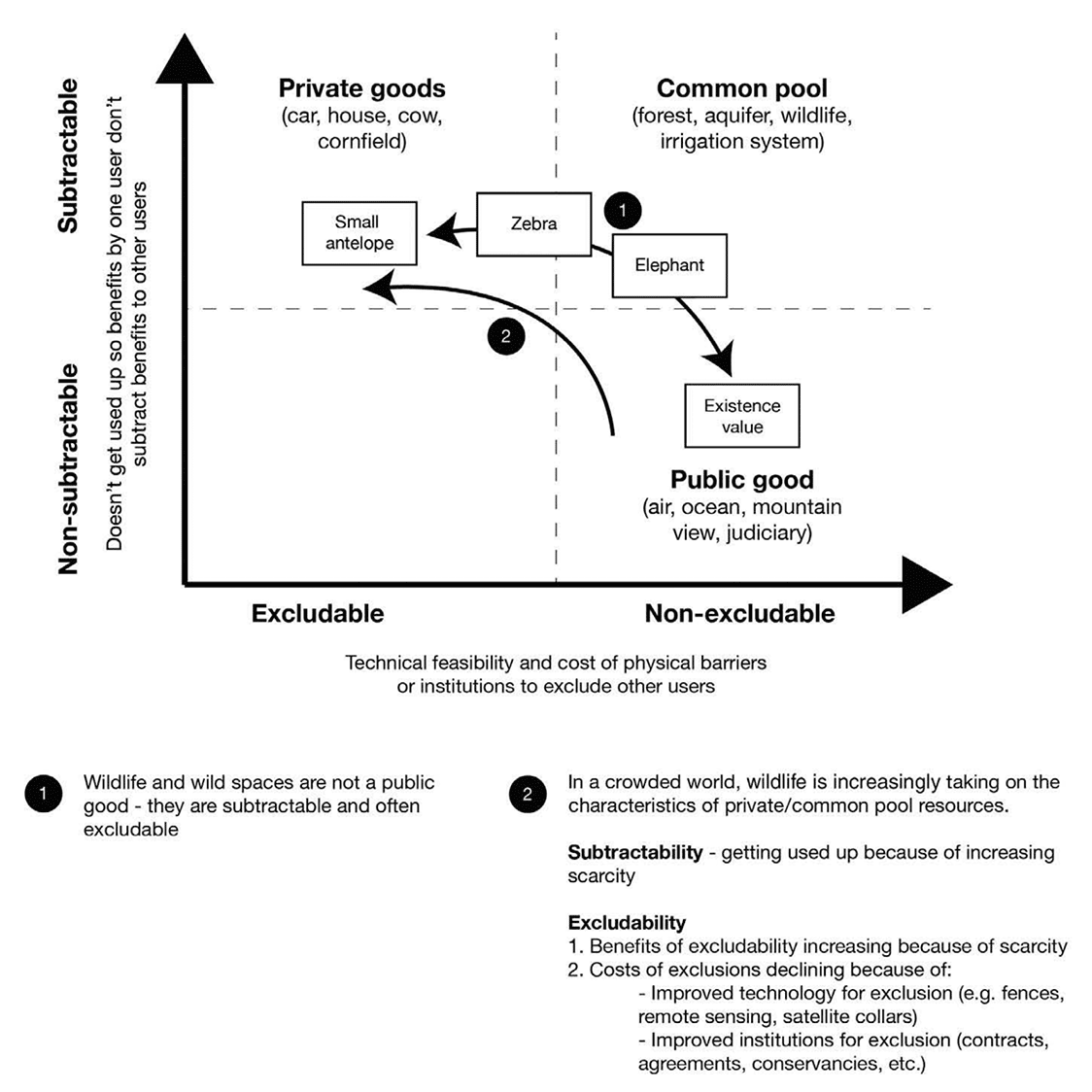

Analyzing wildlife (including forests, drylands, fish, and wildlife) with these criteria suggests that it is not a public good.

Forests and wildlife act much more like private goods, with some common-pool properties, while a few attributes, such as existence values, might be public goods.

Wild resources share with private goods the attribute that one person’s use subtracts from another (‘subtractability’), but they also face challenges of excludability, with both attributes being dynamic in a world of increasing scarcity and technology (Figure 1.2).

Moreover, any simple categorization of wildlife (forests, fisheries, drylands, and wildlife) hides a lot of granularity. Wild animals cover a spectrum from private to common-pool goods because they are clearly subtractable, while the degree to which they are excludable varies.

Wildlife can simultaneously display properties of private, common-pool, and public goods (and even a club good in the form of a private reserve or national park).

As arrow 1 in Figure 1.2 shows, the costs and benefits of a small, territorial antelope, such as a duiker, can be internalized at a very local level as a private good.

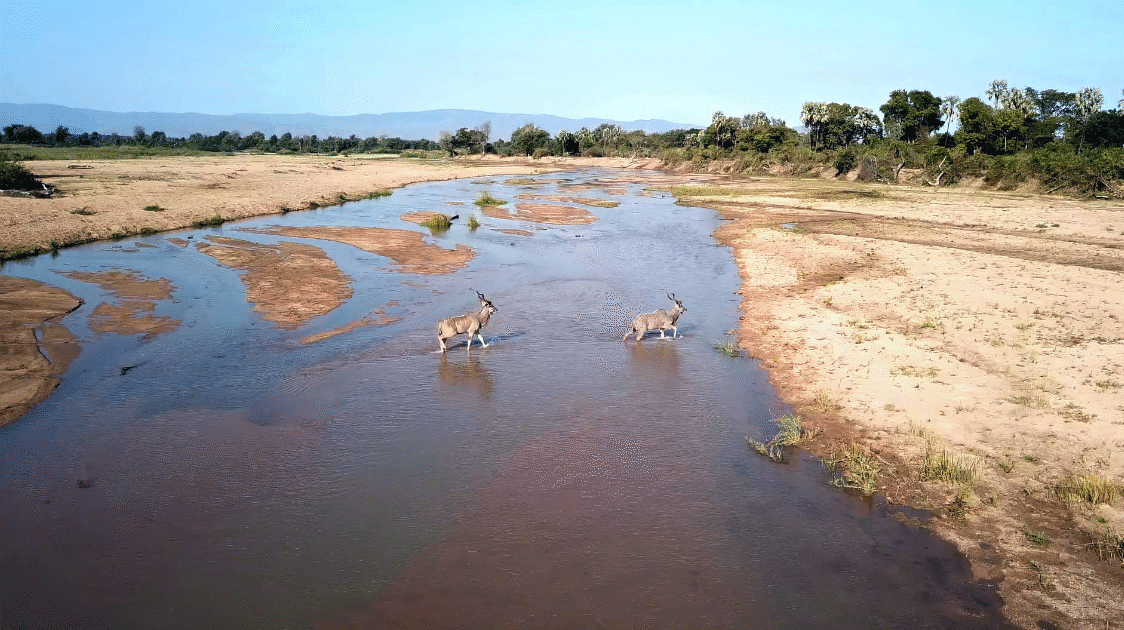

In contrast, elephants and grazing are common-pool resources, while medium-sized antelopes (such as kudu) fall somewhere in between.

Existence and option values might be considered public goods. The properties of individual resources can also be disaggregated in this way.

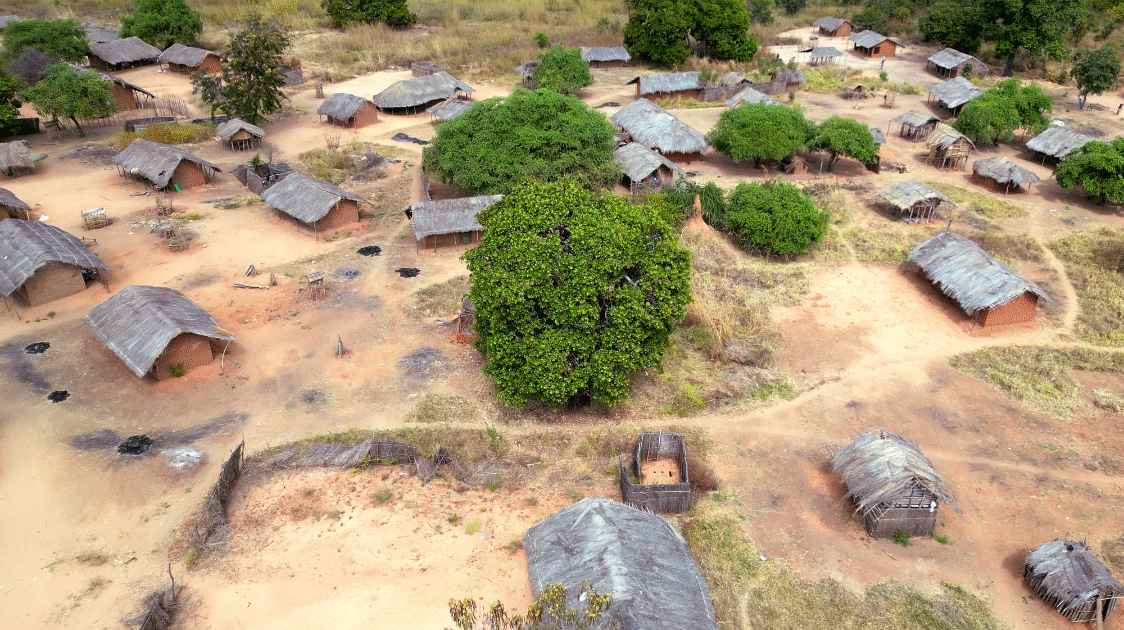

Elephants are an important resource for many communities in Africa in both positive and negative ways (Bond, 1994). The income from an elephant, for instance, is best managed as a private good (at the level of a community).

The elephant itself may be managed collectively by the several villages across which it roams, but the costs it imposes when it tramples fields are private.

Further, elephant policy is national, and elephants have global existence values.

The point is that crude institutions lose sight of this granularity.

‘Solving’ this complexity through a lowest-common-denominator approach by lumping them all as public goods has significant costs in terms of our goals, which is to internalize the costs and benefits of wild resources in ways that encourage full accountability.

A further wrinkle is that subtractability and excludability are moving targets (arrow 2 in Figure 1.2). Not many decades ago, wildlife and forests were perceived as so abundant that they could not be exhausted (non-subtractable), but they are now clearly subtractable, as is the capacity of the atmosphere and oceans to absorb pollution and plastics.

Similarly, technology is providing new methods of exclusion, while the costs of these methods are declining relative to the value of the resources, changing the economics in favor of exclusion.

For example, rhinos are now so valuable that we can afford to use satellite radio collars, microchips, drones, smart fences, automated night-vision equipment, and so on to protect them.

The combined effect of increasing subtractability and excludability is that wild resources are being transformed from public goods of the 19th century into common-pool resources and, often, private goods, at a significantly faster rate than governance regimes can adapt to.

This brings us to the critical issue.

The governance regimes for wild resources no longer match their economic characteristics.

Wildlife, forests, local fisheries, grazing, and communal lands are publicly owned and managed, but are no longer considered public goods, as they are both subtractable and, to a significant extent, excludable.

This implies that reconfiguring their governing institutions, especially proprietary rights, can significantly improve their allocation (and conservation).

African wildlife, for instance, is subtractable and excludable (as it is quite possible to protect wildlife using boundaries, law enforcement and anti-poaching operations), so that private management is theoretically likely to be as effective as, or more effective than, public management.

Ostrom recognized these complexities with her statement, ‘beyond markets and states’. Thus, redefining the jurisdictional authority for wildlife at the level of a community or a private ranch converts it into a private resource.

This has the considerable advantage of enabling us to entrust the allocation of wildlife far more to processes of pricing, markets, and individual choice, where it will look after itself economically, provided it is valuable, and proprietors have sufficient powers of exclusion.

However, some costs and benefits extend beyond the boundaries of individual wildlife properties (i.e., externalities) and are complex.

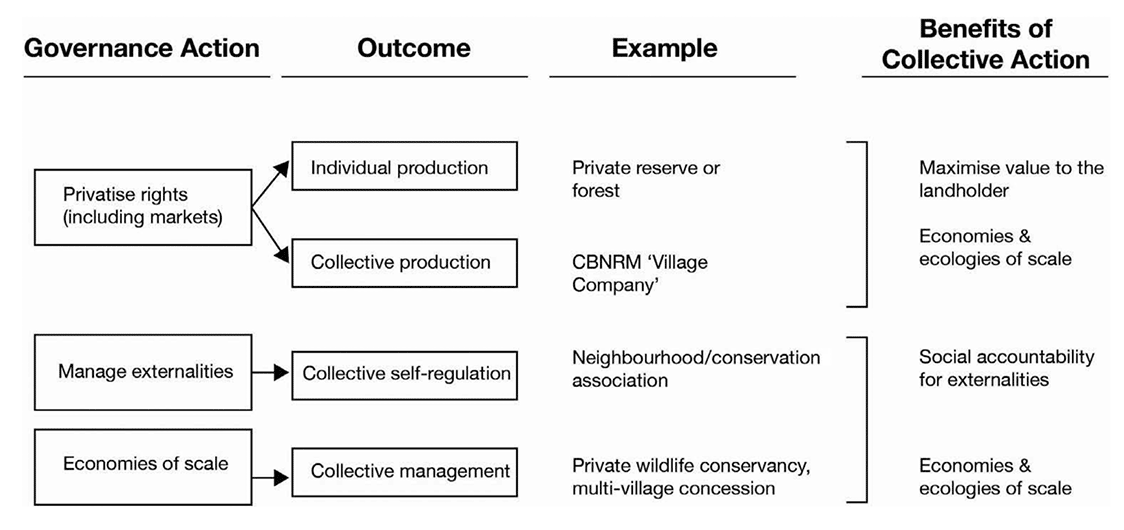

It is here that Ostrom recognized the power of social processes (e.g., peer-to-peer accountability) and collective action to strengthen mechanisms of accountability, thereby complementing privatization.

Collective action often strengthens environmental accountability, but it can also add value by expanding the scale at which environments are managed (Figure 1.3).

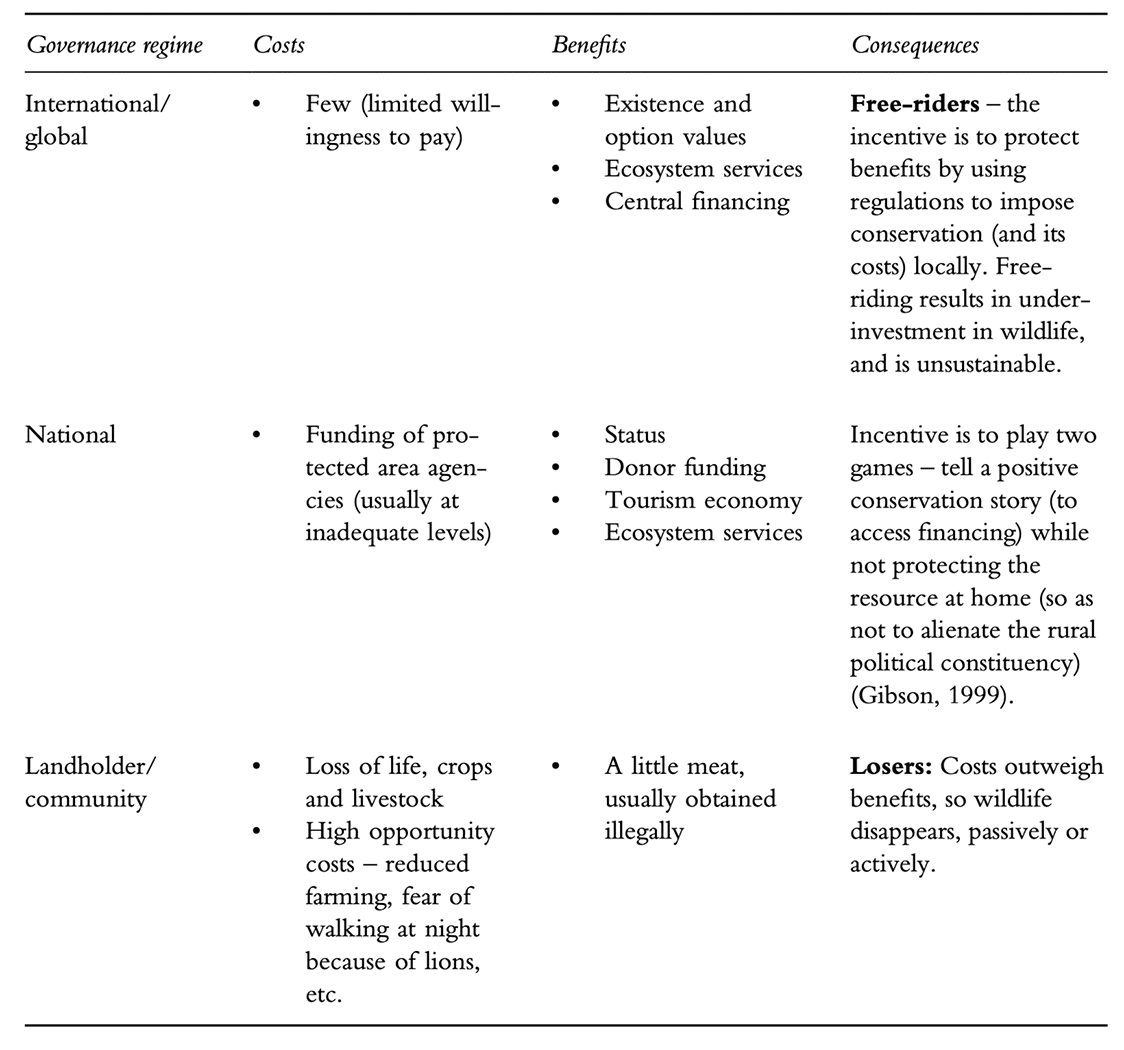

Treating wild species and spaces as public or global goods also results in a highly inequitable allocation of costs and benefits (Table 1.1).

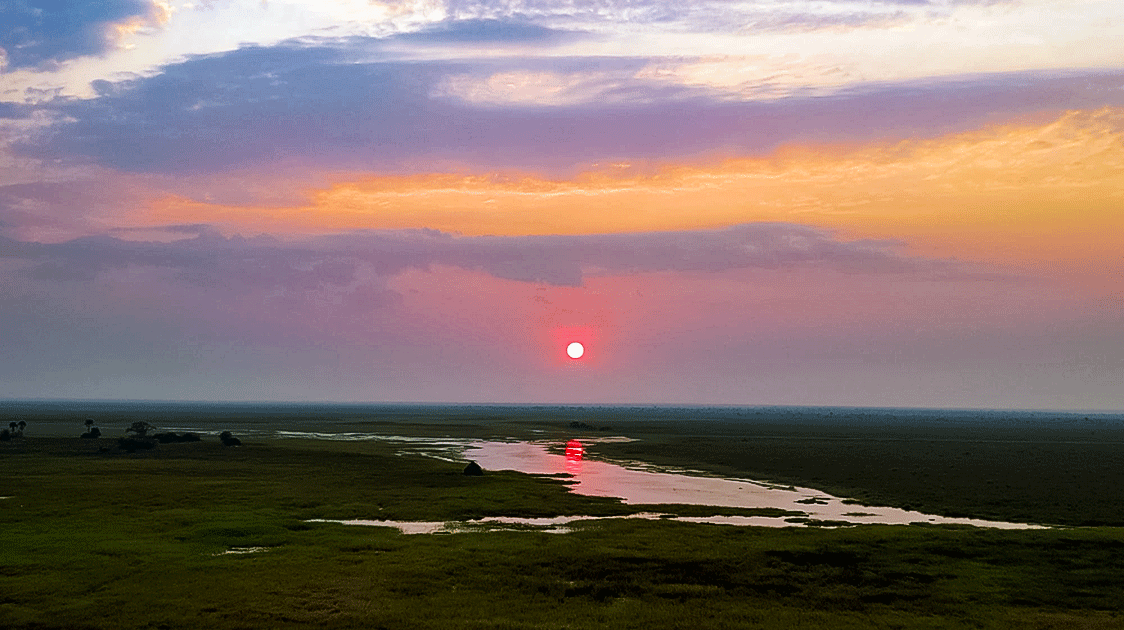

Benefits are global, but costs are local (Wells, 1992). The evidence suggests that this is not sustainable, politically, socially, or economically.

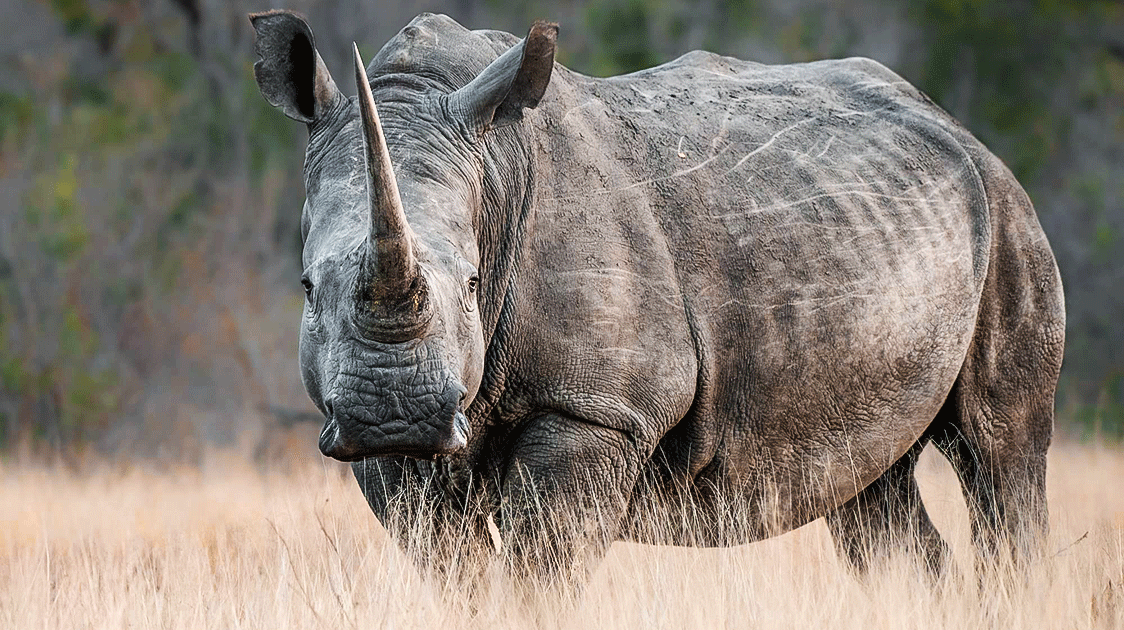

The story of the white rhino, an endangered species in South Africa is a case in point.

Rhinos in South Africa have recovered from fewer than 60 animals in the 1950s to some 20,000 today.

Nearly 6,000 rhinos live on private land in southern Africa.

This is an amazing achievement, but the park managers and landholders who have done so much to bring white rhino back from the brink of extinction view the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) with anger, frustration, or resigned cynicism.

To them, the way CITES has regulated the rhino trade is anti-democratic, ignorant, and counter-productive.

They believe that CITES has been captured by, and benefits, special interest groups.

Having seen a new way to the rewilding of land, landholders view CITES’s decision as extremely retrogressive, imposing an old-fashioned, unworkable, and foreign ideology that wildlife is a public or global asset, which is disrespectful in the extreme regarding their commitment, success, and knowledge in bringing rhinos back from the brink of extinction through private ownership and commercial utilization.

There is broad acceptance and growing evidence that species owned and utilized by landholders are increasing far faster than those that are specially protected (Dry, 2010).

Even national and state park agencies rely heavily on selling live rhinos to cover their costs.

Yet this progress is almost entirely ignored, which is intensely frustrating to South African rhino owners. Indeed, they are unanimous in their opinion that sustainable use has driven the widespread rewilding of the land, and that rhino horn should be traded to fund the conservation of rhinos, the land they inhabit, and the high costs of rhino protection (Rubino & Pienaar, 2018).

However, CITES, in its wisdom, has turned a deaf ear to this evidence and has trodden all over the democratic process and the rights of rhino owners.

Rhino owners argue that CITES has infringed upon their property rights to rhinos without compensation, potentially affecting a potential annual income of around $250 million.

CITES has not replaced this income with alternative funding models to cover the burgeoning costs of rhino protection, nor have they compensated rhino owners for their loss of rights and revenue.

Philanthropy is indeed financing several hundred pop-up rhino NGOs, but landholders are curious about how much money is raised and what happens to it.

Rhino owners do not need charity.

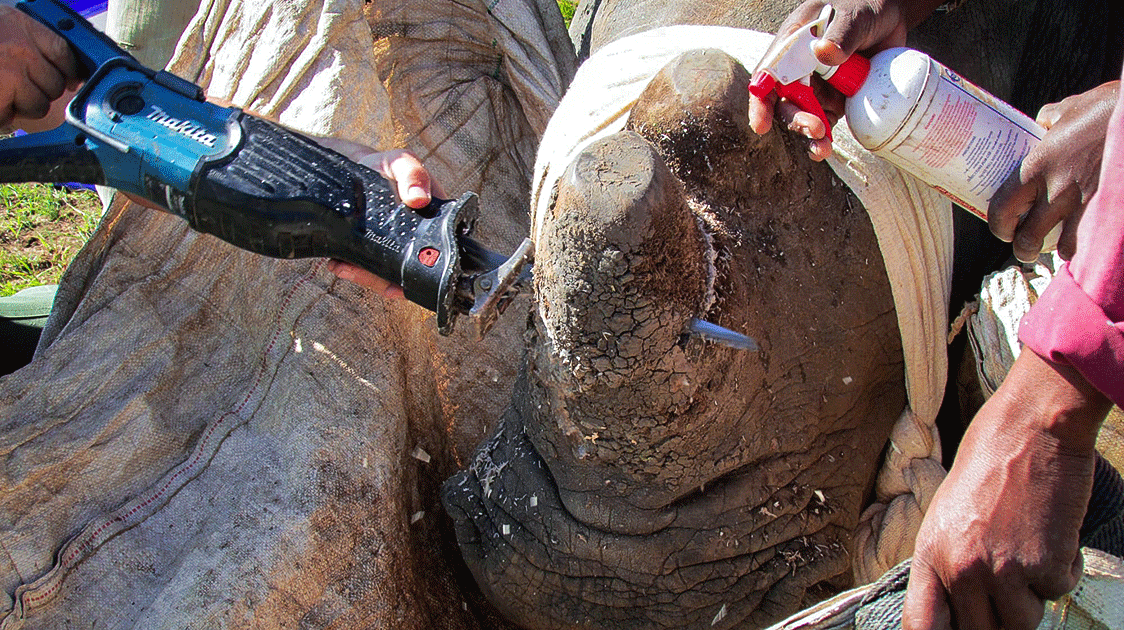

A rhino’s horn grows about 10 cm per year, with females producing 0.75 kg and males 1.5 kg annually. This can be harvested every 2 to 2.5 years (or approximately ten times in a rhino’s lifespan), before the horns become too attractive to poachers.

Rhinos are truly the goose that keeps on laying the golden egg. Removing the horn is not too different from fleecing a sheep.

However, a horn from a single rhino is worth approximately $50,000 per year, and allowing landholders to retain this value would transform vast areas of southern African landscapes back into wildlife habitats.

Approximately 20% of South African farmland has already been rewilded, funded by the sustainable use of wildlife, primarily through hunting and the sale of meat and live animals.

The CITES rhino decisions provide a poignant example of the persistence of bad regulations that are not working.

These decisions originate in ideologies that define rhinos as a public or global resource.

They persist because they benefit the status quo, through status, employment, and even money.

Yet, like colonialism, the parties most affected by the rules have little say in writing them.

Rhino producers have been stripped of a valuable asset without their consent, and now bear the huge costs associated with criminality, which is itself partially a result of the rhino prohibition.

The southern African rhino population, which was recovering nicely, has now been put quite firmly on a pathway towards extinction by CITES.

Rather than supporting an approach that was clearly working, CITES has adopted a public goods approach that is unworkable because it lacks a reliable financing model.

This is irresponsible beyond belief.

Yet the special interest groups that overruled the wisdom, economic rights, and democratic wishes of rhino producers will bear no personal accountability for this decision.

A combination of special interest and highly centralized governance systems is toxic to the common good, as explained by Mancur Olson (2000).

(Prof Brian Child is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida and the Life Through Wildlife Project director. His book, “Sustainable Governance of Wildlife and Community-Based Natural Resource Management”, is available on Amazon.)