Trapping and Snaring: Conservation’s Double-edged Swords

By Hank’s Voice

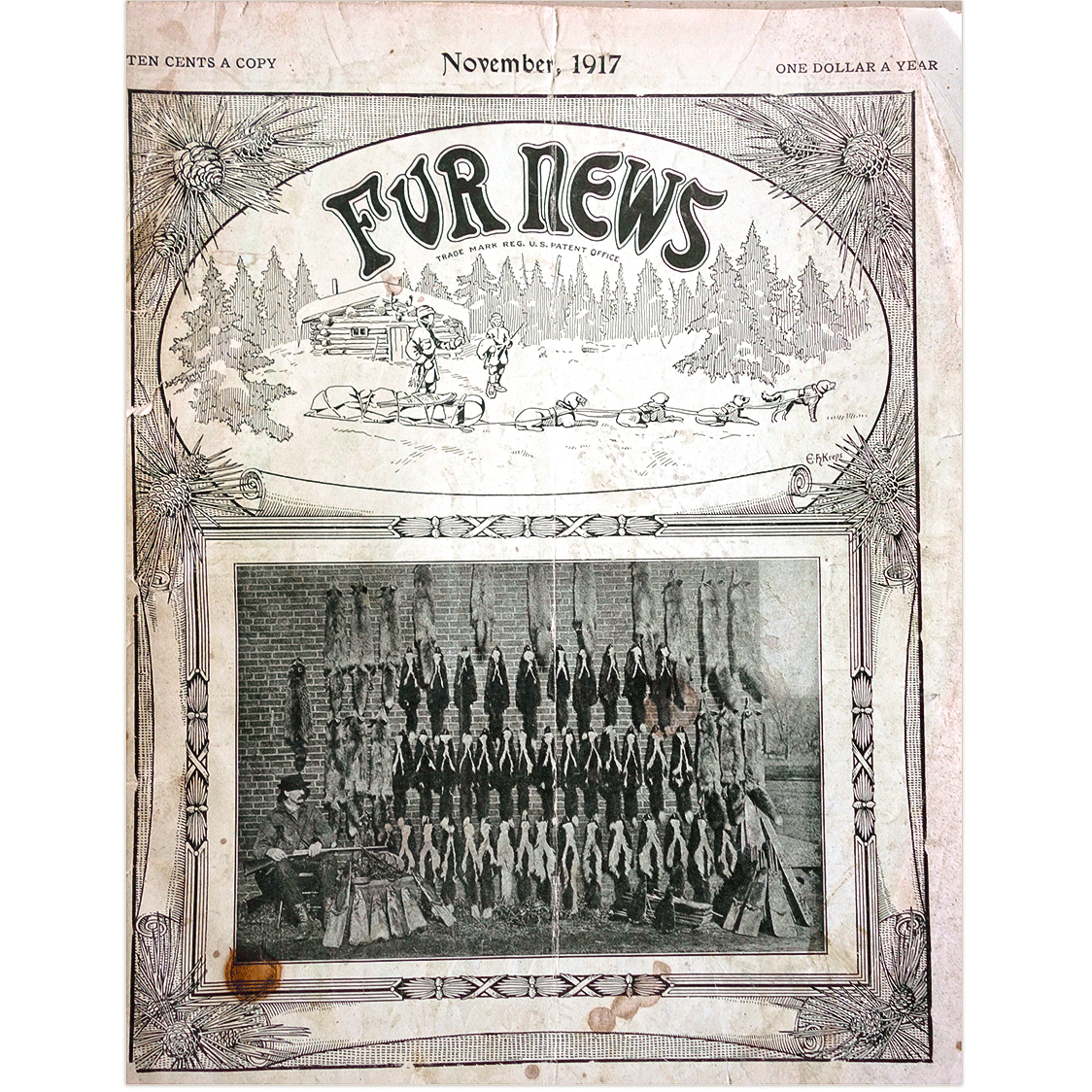

People have trapped animals in various ways for centuries, primarily for food, furs, and pest control. One form, snaring, is an ancient technique depicted in cave drawings thousands of years old, and steel traps were first mentioned in late 16th-century literature.

Trapping was also a chief article of commerce that funded European colonization of continents in the 17th and 18th centuries, exerting a significant influence on the history of the US and Canada.

Trapping continues to this day, ranging from the very basic killing of rodents who invade our homes to harvesting furbearers for economic and wildlife management purposes, scientific research/translocation projects, poaching for bushmeat, retaliation and procuring witchcraft talismans.

As with any offtake of wildlife, however, the difference between a technique contributing to conservation vs harming it lies in its application and associated regulations. Whereas legal, restricted offtake can essentially fund and implement conservation, illegal, nonselective, and unlimited methods typically detract from and hinder such efforts at often huge costs.

In North America, trapping is scientifically monitored and highly regulated under the auspices of trained professionals and has enabled furbearer and other wildlife populations to flourish and expand. It has restored many species to ranges they were formerly extirpated from (due to no regulations and thus overharvest), which has increased the current public harvest potential and ecosystem services these species provide.

States and provinces have adopted various ways to ensure trapping is sustainable and trappers are legally accountable. These include:

- mandatory trapper education course requirements conducted by certified instructors,

- periodic (often daily) trap checks,

- timely harvest reporting to ensure quotas are not exceeded,

- restrictions on sizes and types of traps, designated trapping areas for certain species,

- breakaway testing for snares,

- and mandatory identification tagging of traps.

Furs are sealed (examined and tagged), with carcass data collected (reproductive rates, food habits, sex and age ratios, etc.), which helps to manage populations responsibly.

Extensive, expensive research, including computer simulations, is conducted to design better, more humane, and effective traps. Nontarget species must be released, with any fatalities reported and surrendered to state wildlife agencies. Trapping is often limited to when furs are in prime condition and/or the annual rearing of young is passed.

Governments, universities and NGOs, as well as private citizens, utilize trapping for public health and safety (nuisance animal or disease control), property and agricultural damage control, to protect other wildlife (like eliminating invasives or protecting imperiled flora and fauna from damage or depredation), translocations (ironically, live-trapping formerly lethally trapped species to repopulate extirpated areas), and as a revenue stream supplying the wild-sourced fur market—a multi-billion dollar global industry, benefiting about 270,000 mostly rural dwellers domestically.

Wildlife populations legally trapped or managed indirectly via trapping are valuable natural resources that, if properly managed, can be sustained for the benefit of both humans and nature. A basic conservation tenet, wherein the required licensing fees are returned, in part, to aid good conservation efforts.

This is in stark contrast to poaching via trapping, an enormous scourge and high conservation cost constantly battled throughout the African continent.

Traps and snares are ideally suited to poaching, as they are simple, silent, easy to set in large numbers, discrete, and often difficult to detect unless patrolling on foot.

Crude gin traps are often employed, mechanical devices designed to catch an animal by the leg or head using spring-operated jaws and a triggering mechanism, usually with serrated edges or “teeth”.

When constructed from vehicle leaf springs, they are big enough to capture buffalo and elephants. Such traps are obsolete in North America, where modern designs either lethally dispatch an animal as swiftly as possible or live-capture it as unharmed as possible (via padding, swivels, shock-absorbing springs, etc.).

Snares are also widely employed in Africa and can be crafted from easy-to-obtain or even stolen materials like natural fibers, rope, nylon, fencing and other wire, telephone and utility lines, bicycle brake cables, and burnt tires.

Ironically, fences intended to conserve wildlife often have their construction elements pillaged to poach it instead, unless they are made of kinked, mesh-type materials.

And the expansion of electric grids, good for increasing tourism that can potentially contribute to conservation, also provides more snare materials to steal.

One person can set many snares rapidly, maybe checking them once a week. Indiscriminate sets, placed year-round at places of high wildlife traffic or congregations, like trails, along roads, or at waterholes, can result in lots of wastage. It is estimated that up to 90% of animals caught may rot in some places, including, of course, many non-target species, like endangered vultures.

Unlike North American snares that offer selectivity, African snares typically lack reliable locks, loop stops that prevent opening or closure beyond a certain point, or breakaway devices that allow animals to escape completely freely based on size. Therefore, animals not killed often suffer severe injuries to trunks, necks, legs, torsos, and feet.

Bushmeat poaching can be so severe that it affects the viability of hunting blocks, negatively impacting predator and prey populations.

And it is a common problem in many national parks too.

Tens of thousands of snares are regularly removed from certain areas, and it’s likely that many more remain on the landscape, as they’re easy to replace and rarely all collected if partial losses or confiscations occur.

Traps and snares are only as good or bad for conservation as how they are utilized.

They are dangerous and damaging tools when employed illegally and indiscriminately, yet effectively contributing when used selectively in legal, regulated fashions.

Since the latter option is unlikely to be obtainable in Africa, poaching via traps and snares will likely remain a passive, pervasive problem plaguing conservation efforts and requiring constant vigilance, counteracting, and significant funding.