The Right to Decide?

By Prof Brian Child

Key Takeaways:

- Rural African Communities should be allowed to decide whether to use a natural resource or not, and to benefit from it if they do.

- Community conservation can be classified according to the degree of rights devolution.

- Wildlife legislation in Zimbabwe was centered around the “King's Game”, a public asset, until proprietorship was devolved to landholders.

- Despite ineffective results, there is an over-reliance on negative incentives and wildlife regulations that often do more harm than good.

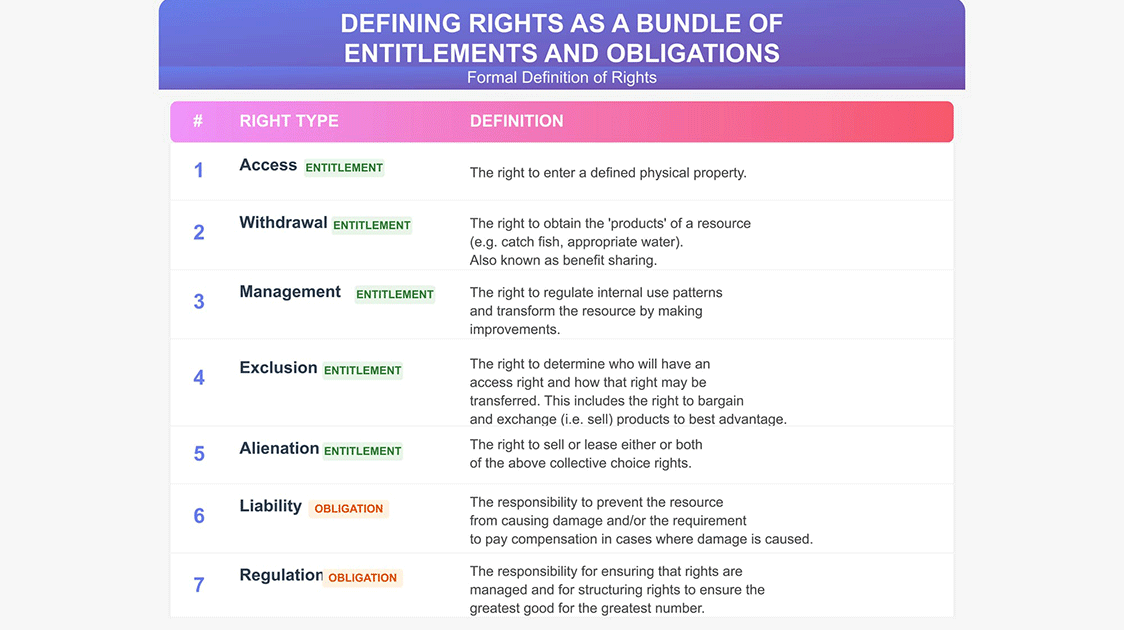

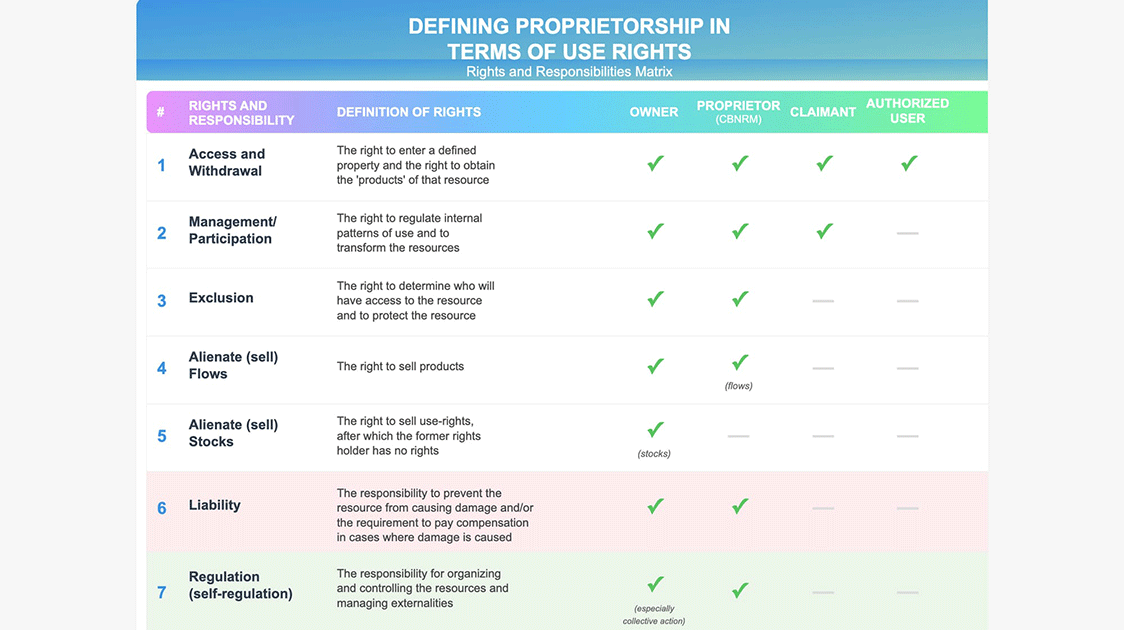

Defining proprietorship as a bundle of rights

Proprietorship is a complex concept that concerns the acquisition by an individual or organization of a bundle of rights and responsibilities over resources.

In the context of Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM), Murphree (1991) defines proprietorship as: a sanctioned use right, including the right to decide whether to use the resources at all, the right to determine the mode and extent of their use, and the right to benefit fully from their exploitation in the way they choose … [and to] determine the distribution of such benefits and determine rules of access. (Murphree, 1991)

Murphree’s definition is operationalized in the CAMPFIRE case study as the right to use, sell, benefit from, and manage wildlife. A more widely used definition is that of Schlager and Ostrom (1992), who define property as including rights of access and withdrawal, management, exclusion, and alienation.

However, rights are associated with responsibilities and liabilities. Thus, CBNRM requires the devolution to communities of the rights to access and use resources and to manage them, to exclude others from using them, and to sell them (or at least the annual production from them).

CBNRM is predisposed to fail without strong rights and preferably title, across this range of entitlements. We can classify community conservation according to the degree of rights devolution and the corresponding level, with CBNRM corresponding to fully devolved citizen control (or privatization) in Arnstein’s ladder of participation.

Where CBNRM initiatives disappoint, the cause often lies in the failed or aborted devolution of this full range of rights (the other primary cause of failure is weak systems of micro-governance and elite capture).

There is some debate about full alienation.

In Mexico, communities have title to their land and, following recent legislative changes, can sell their land after an agreement is reached by a supermajority of the community (Bray et al., 2005).

This seldom happens, except in cases where communities are incorporated into major expanding urban conurbations. In the main, CBNRM requires only a non-transferable community title, which reduces the risk of exploitation and landlessness.

Liability and regulation

I have expanded on Schlager and Ostrom’s (1992) definition of rights, as issues of liability and regulation can significantly alter the nature of rights.

I will use the fascinating example of Zimbabwe to illustrate how this principle is often ignored when a country nationalizes wildlife. Like much of the colonial world, early Zimbabwean wildlife legislation was built around the principle of the ‘King’s Game’.

Wildlife was legally defined as a public asset, owned by the state on behalf of the people. However, contradictions inevitably arose with the management of a public asset on private land.

In the mid-1970s, the government prosecuted a farmer for shooting wildlife, including royal game. Claiming he was protecting his cattle, land, and grazing resource, the farmer flipped the argument around.

He sued the government on the basis that if the state claimed ownership of wildlife, it was also liable for the costs of that wildlife to his ranch, including grazing and damages to crops and livestock.

The court agreed with the farmer, making conventional wildlife laws unworkable, especially as the legal definition of wildlife could be interpreted to include pest species such as quelea and locusts.

This resulted in an ingenious legal innovation: in the 1975 Parks and Wildlife Act, wildlife was res nullius, but proprietorship was devolved to landholders.

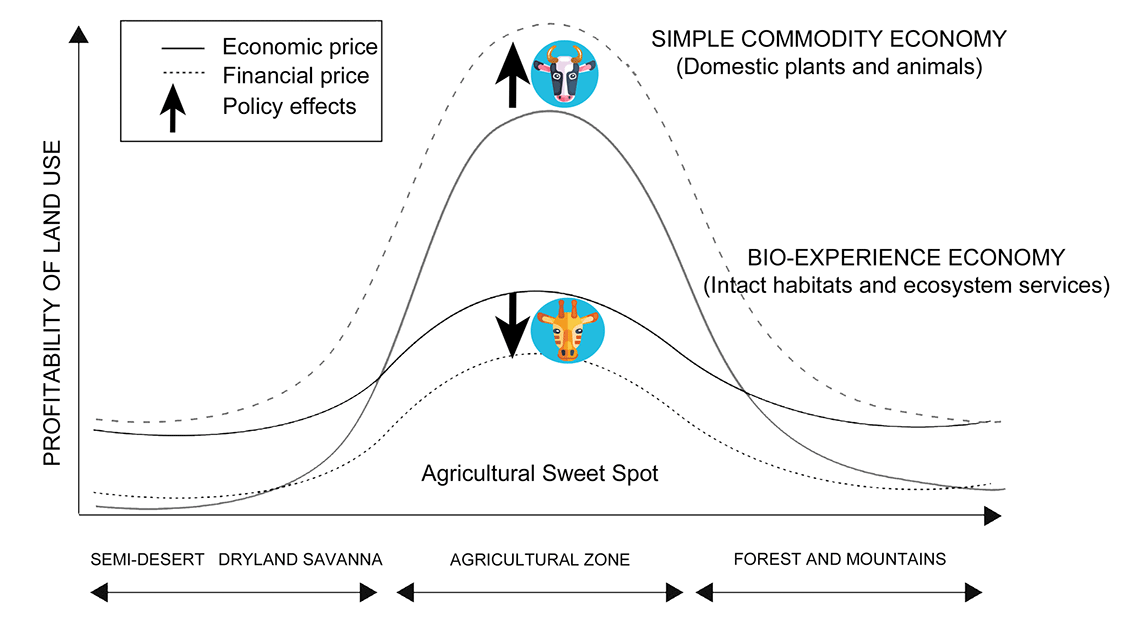

Regulatory restrictions on property rights can significantly alter the nature of rights and radically shift the distribution of costs and benefits among different constituencies.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), for example, removed the right of landholders to sell rhino horn or elephant leather without their consent and without compensation.

These actions might be considered normal for wildlife but would be considered theft if applied to private goods, such as cars or cows, and could easily be reversed in the courts, as recently happened with the internal sale of rhino horn in South Africa.

Even eminent domain, or the right of a government to expropriate private property for public use, usually requires fair compensation. Conservation relies heavily on regulation and often escapes paying the full costs of appropriation due to the history of public ownership of wildlife and the limited rights of communities that coexist with it.

Despite ineffective results, there is an over-reliance on negative incentives and wildlife regulations that often do more harm than good. In South Africa, for example, less regulated species have recovered much faster than heavily regulated ones (Dry, 2010).

This is because regulators seldom assess the effect of regulations on the all-important economic and financial curves, and differential regulation and taxation reduce the competitiveness of wild species.

The efficacy of regulations in wildlife conservation needs critical review, with far greater consideration of positive incentives (Murphree, 1999). The question of who the regulator should be also deserves more attention.

While the state is the primary regulator, decentralized self-regulation through associations and localities is highly effective. Centralized regulation is costly, and there are many advantages in decentralized or devolved self-regulation.

This usually requires (a) empowering participants to self-regulate through associations, landholder communities, standards, and certification mechanisms, and (b) inspecting the quality of this regulation periodically.

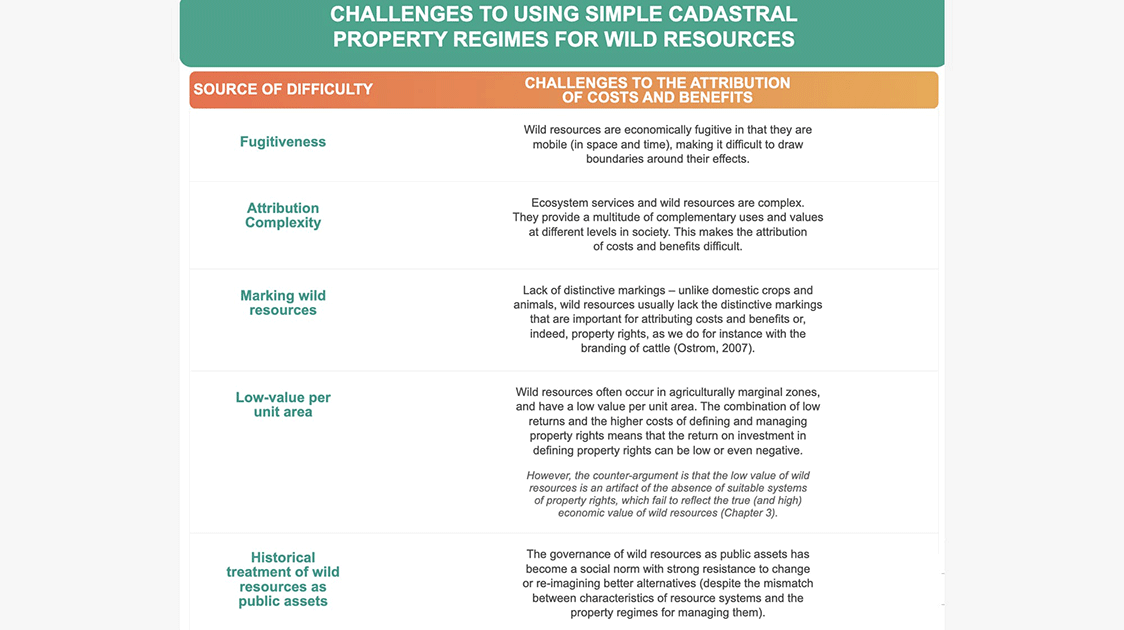

Internalizing costs and benefits, and the problem of fugitiveness and attribution

Property regimes fulfill the critical economic function of setting prices correctly by internalizing the costs and benefits, so that the user is fully accountable for their actions. This is relatively easy for private goods, such as cars and houses, but is more difficult for wild resources for several reasons.

Wild resources are inherently fugitive in space and time, so their effects spill over the boundaries of simple cadastral property regimes. Being associated with complex ecological systems and multiple values, it can be difficult to attribute costs and benefits to individual actions and investments.

This is similar to the problem of marking; it is easy to attribute the damage caused by a cow that is owned and branded, but who do we blame for the damage caused by a wild buffalo?

Finally, the costs of marking and drawing boundaries around wild resources are relatively high, especially compared to the relatively low productivity of wild systems (Ostrom, 2009).

Historically, rather than designing property institutions suited to wild resources, policymakers have defined wild resources as public assets, a perspective that now warrants reconsideration.

(Prof Brian Child is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida and the Life Through Wildlife Project director. His book, “Sustainable Governance of Wildlife and Community-Based Natural Resource Management”, is available on Amazon.)