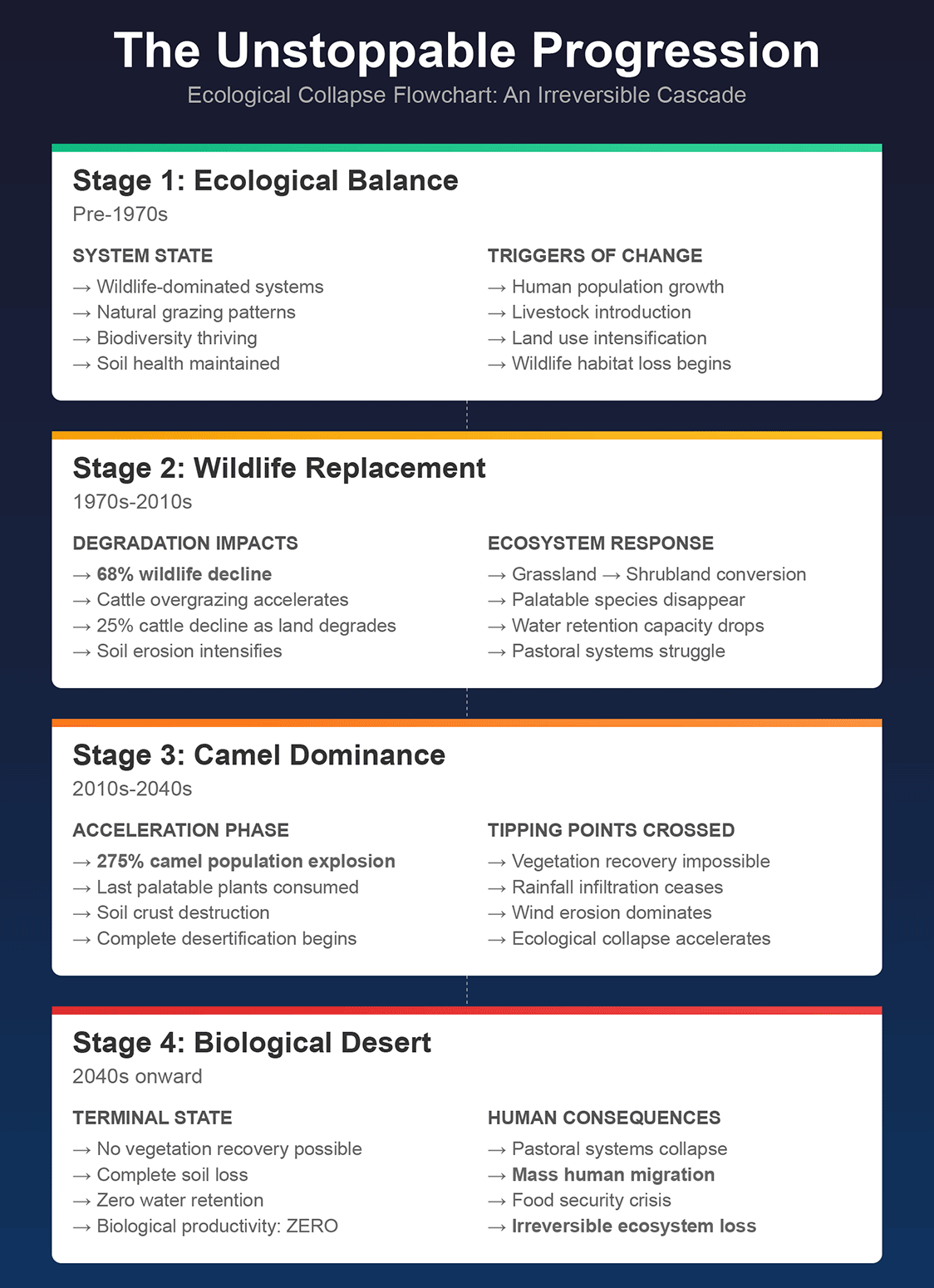

The Inevitable Cascade: From Wildlife to Cattle to Camels, Comparing the Desertification of Arabia and East Africa

Key Takeaways:

- On the rangelands in Kenya, wildlife was replaced with cattle, which is presently being replaced with camels.

- Although this appears to be an adaptive change, it is the next step in an unstoppable progression to ecosystem collapse.

- The Arabian Peninsula provides a chilling preview of what's to come.

- By rendering wildlife worthless, the Kenyan rangelands will become a permanent wasteland.

The Three-Stage Collapse of Rangeland Ecosystems

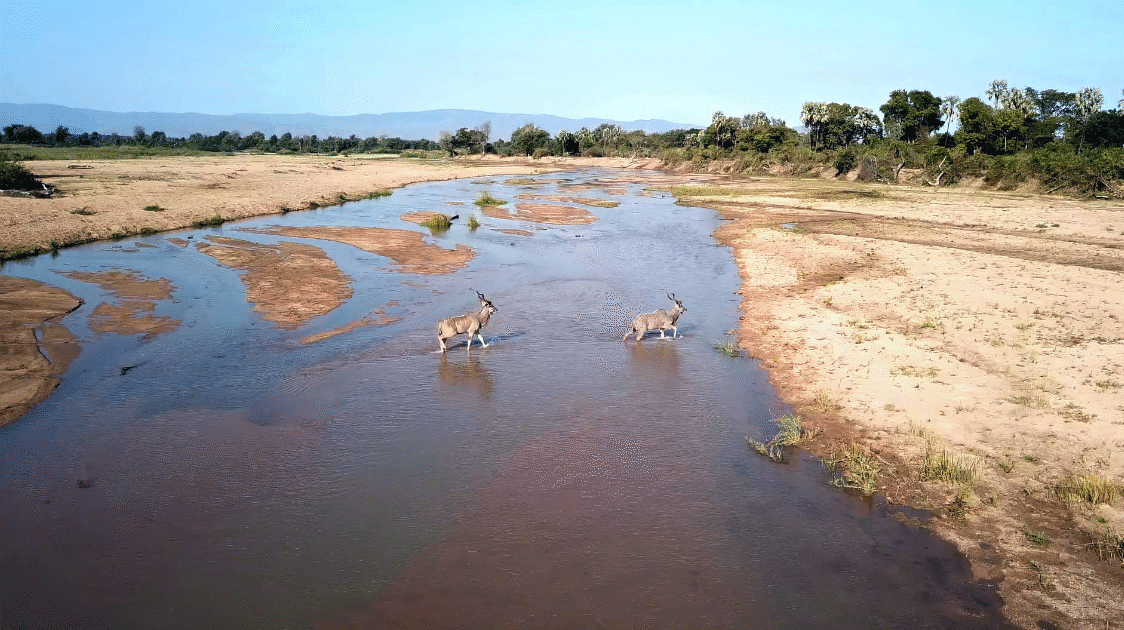

Stage 1: The Original State - Wildlife Dominance

Before human intervention transformed the rangelands of Kenya and the Arabian Peninsula, these ecosystems supported vast populations of wild ungulates in a sustainable balance that had evolved over thousands of years.

These native species, including gazelles, oryx, wild asses, and various antelopes, had co-evolved with the vegetation, creating a complex web of grazing patterns that maintained ecosystem health.

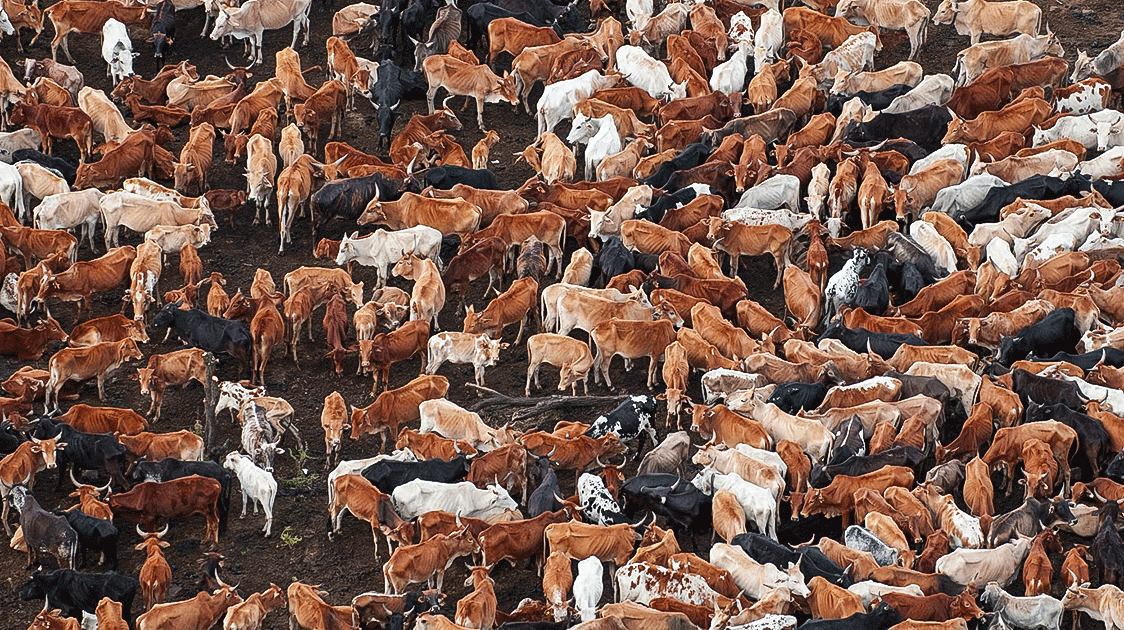

Stage 2: The Cattle Invasion - First Wave of Destruction

The introduction and expansion of cattle fundamentally disrupted these ancient systems. Research from Kenya documents the catastrophic replacement of wildlife with livestock. Between 1977 and 2016, wildlife populations declined by 68%, with some endangered species experiencing decreases of 72-88%, threatening their very survival.

1977 was also the year that safari hunting was banned in the country.

A coincidence?

Species like warthog, lesser kudu, Thomson's gazelle, eland, oryx, topi, hartebeest, impala, Grevy's zebra, and waterbuck now face population collapse.

During this same period, livestock biomass became 8 times larger than wildlife biomass by 2011-2013, compared to 3.5 times larger in 1977-1980. The study notes that livestock were evidently replacing wildlife across Kenya's rangelands, which cover 88% of the country's land surface.

Throughout much of history, rangeland was freely grazed by cattle and sheep during the growing season, usually without concern for their impact on soil, vegetation, water, or ecosystem services.

This unregulated grazing fundamentally altered plant communities, degraded soils, and destroyed the habitat complexity that wildlife required.

Stage 3: The Camel Transition - The Final Desertification

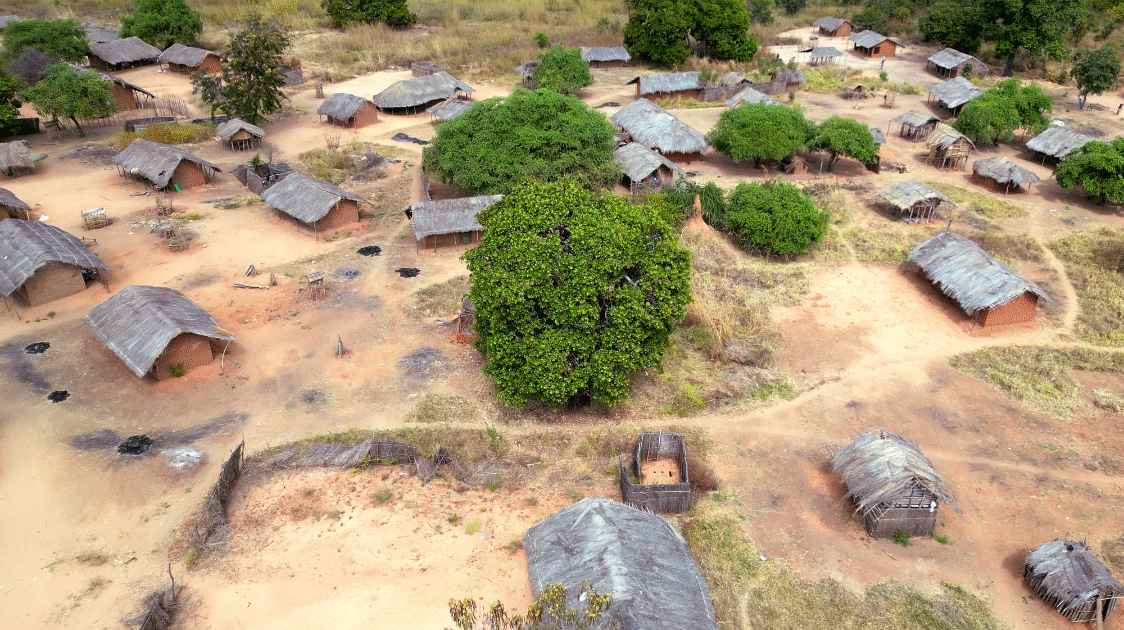

Presently, as cattle-degraded rangelands can no longer support these water-dependent grazers, pastoralists are making what appears to be an adaptive choice, but, in reality, it is the next step in complete ecosystem collapse: the shift to camels.

This transition is already well underway. Traditionally cattle-keepers, the Borana people have abandoned their cultural identity to embrace camel production.

Kenya's camel population exploded from 800,000 to 3 million between 1999 and 2009.

Critically, even as cattle numbers declined by 25.2%, the total livestock biomass barely decreased (only 4.6%) as camel, sheep, and goat numbers expanded to fill the gap.

The study explicitly states: "the change in herd structure from cattle to camels, sheep and goats by the pastoralists is probably an adaptation to rangeland degradation linked to intensification of land use."

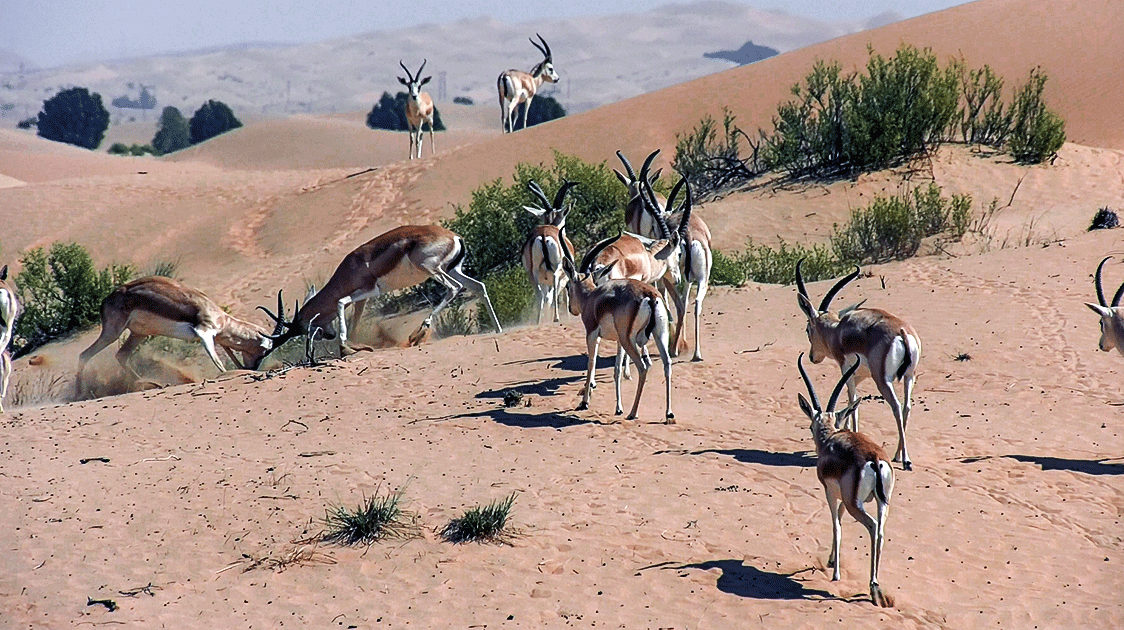

The Arabian Peninsula: A Window into Kenya's Future

The Arabian Peninsula provides a chilling preview of Kenya's inevitable future. Research from the UAE reveals the endpoint of this progression:

- 90% of all land is affected by camel grazing

- 44% is severely or very severely degraded

- Complete elimination of palatable plant species

- Transformation into a biological desert

Excessive camel grazing is the single greatest threat to the inland desert ecology. The UAE now has nearly three camels per square kilometer, a density 25 times higher than that of Saudi Arabia.

These camels receive supplementary feed, allowing their populations to explode beyond any natural carrying capacity.

The Irreversible Nature of Camel-Induced Desertification

Why Camels Complete the Destruction

Camels represent the perfect agent for final desertification because:

- They survive where cattle cannot: requiring less water and eating plants that cattle won't touch, camels continue to degrade land long after cattle would have died off.

- They eliminate the last vegetation: camels consume thorny bushes, halophytes, and aromatic species, which are usually avoided by other domestic herbivores.

- They prevent regeneration: By eating seedlings and destroying soil crusts, camels eliminate any chance of natural recovery.

- They're economically sustained: Producing milk even in severe drought, camels provide income that maintains their populations regardless of ecological damage.

The Feedback Loop of Destruction

Studies from both regions reveal a vicious cycle:

- Overgrazing reduces vegetation cover.

- Reduced cover increases soil erosion.

- Erosion reduces water infiltration.

- Reduced water means only the hardiest plants survive.

- These plants are exactly what camels prefer.

- Camel populations increase while vegetation decreases.

- The cycle accelerates until complete desertification.

Evidence of Irreversibility

The Point of No Return

Research on desert restoration suggests that natural recovery in degraded drylands can take over 200 years, even for partial recovery of species. In severely degraded systems, the study notes, "recovery through natural processes following disturbance is not necessarily possible."

Even after complete camel exclusion, recovery required:

- Artificial water provision.

- Replanting with 6,000 indigenous trees and shrubs.

- Introduction of wild ungulates at carefully managed densities.

- Continuous active management.

Without such intensive intervention, which is impossible across the vast rangelands of Kenya, the progression to desert is irreversible.

Why Change Won't Come Until It's Too Late

The socio-economic dynamics ensure this destruction will continue to completion:

- Economic trap: In some communities, camel milk now accounts for 35-40% of household income. Families cannot abandon this income source even as their camels destroy the last vegetation.

- Inequality accelerates degradation: Those who can afford camels survive while others become destitute, forcing them to overexploit any remaining resources for survival.

- Cultural momentum: The shift from cattle to camels represents not just an economic change but a fundamental cultural transformation that, once begun, cannot be reversed.

- Policy paralysis: Governments face an impossible choice between supporting pastoral livelihoods today and preserving ecosystems for the future.

Rock Bottom: What It Will Look Like

Based on the Arabian Peninsula experience, Kenya's rangelands will reach these conditions:

- Complete loss of palatable perennial plants: Already documented in heavily grazed areas of the UAE.

- Dominance by toxic or thorny species: Only plants with extreme defenses survive.

- Soil erosion to bedrock: Loss of millennia of soil accumulation.

- Collapse of pastoral systems: Even camels cannot survive on bare rock.

- Mass human displacement: Millions of pastoralists are becoming environmental refugees.

This study highlights the need for reduced grazing pressure throughout the Dubai inland desert, particularly on gravel substrates. But such calls come after 44% of the land is already severely degraded - too late for natural recovery.

Conclusion: The Price of Inevitability

The progression from wildlife to cattle to camels represents not adaptation, but collapse, as each stage removes another layer of ecological resilience until nothing remains. Kenya is currently transitioning from Stage 2 to Stage 3, following precisely the path that led to 44% severe degradation in the Arabian Peninsula.

The science is unequivocal: "When desert ecosystems are severely disturbed, natural recovery may be slow or not provide functions for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services." In the hyper-arid conditions created by camel overgrazing, that "or" becomes "will not."

The tragedy is that this outcome, while preventable in theory, is inevitable in practice.

The economic necessities of today override the ecological necessities of tomorrow. By the time the consequences become undeniable, when even camels cannot survive on the denuded landscape, it will be far too late.

The rangelands of East Africa, like those of Arabia before them, will have crossed the threshold from ecosystem to desert, from recoverable to lost, from thousands of years of pastoral heritage to permanent wasteland.

Politicians and animal rights activists will point to "climate change", the default scapegoat.

But history will show that rendering wildlife worthless, along with poor rangeland management and the effects of the "tragedy of the commons", are the real reasons for the emergent catastrophe.