The Critical Importance of Disruption

By Prof Brian Child

The last few centuries have seen the most rapid transformation of human society in history. The misery of an agrarian economy based on feudal ownership was replaced by the current era of prosperity and personal freedoms that so many of us are fortunate to enjoy.

This unparalleled wealth is rooted in fundamental changes in institutions, with critical lessons for the governance of Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM).

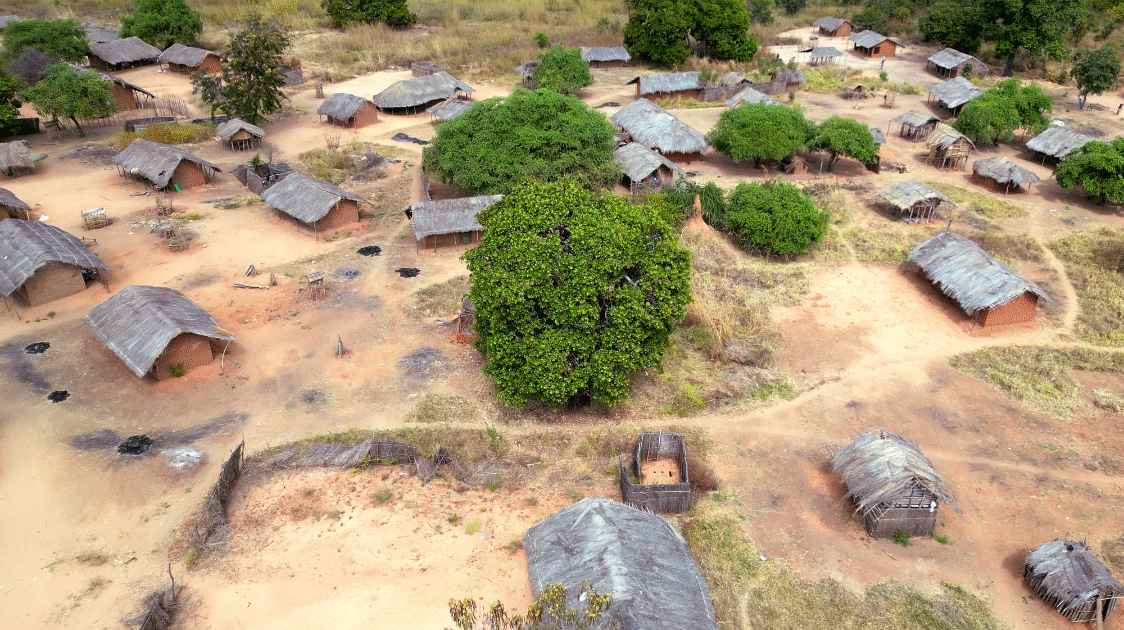

Most of us lived in villages and small towns two hundred years ago. We made things ourselves and exchanged them with people we knew. People who deal with each other repeatedly in small-scale political and economic transactions develop high levels of trust, cooperation, and reciprocity; if someone cheated, the whole village would soon know.

Transaction costs were low because people dealt with each other repeatedly, but this world of small-scale artisanal production (tinker, tailor, baker, blacksmith) lacks economies of scale and can only take prosperity so far.

Adam Smith published An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in 1776 amidst the economic excitement of the unfolding Industrial Revolution.

He recognized that wealth is created by converting raw materials into useful products and through specialization, which in turn depends on exchange – the highly effective pin-maker of Adam Smith’s story needs to trade his pins for food.

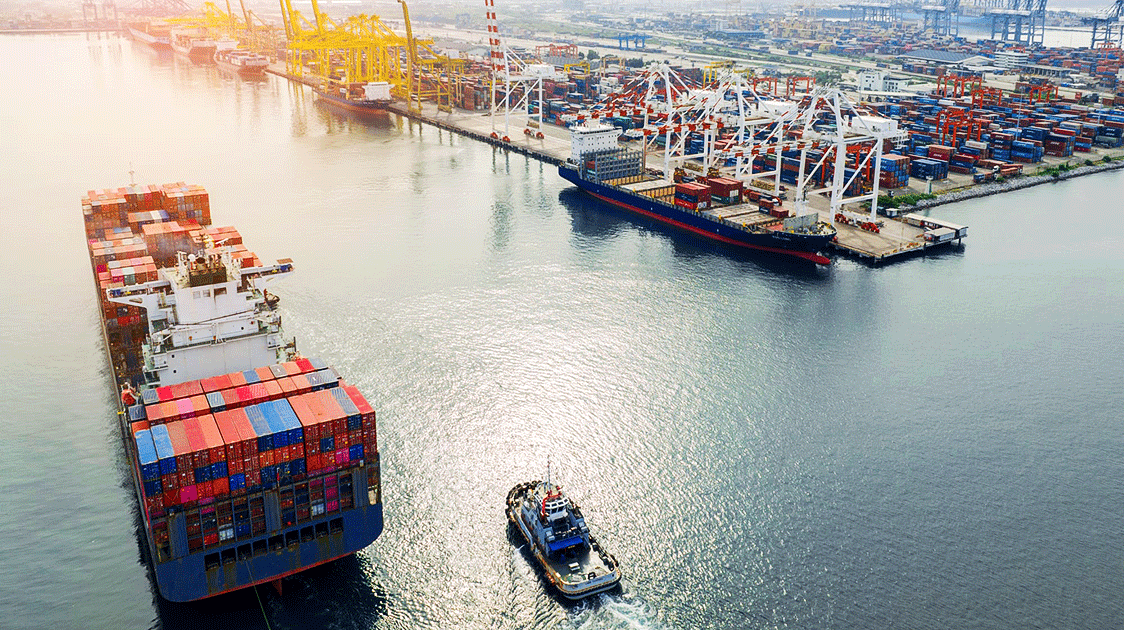

Extreme specialization and global exchange are the sources of the enormous wealth we enjoy today, allowing a dramatic transition from artisanal production to a global economy.

This is not automatic.

Institutional economists like Douglass North have shown that high-quality rules or institutions make this transformation possible. We no longer live in villages where we deal with each other repeatedly and can prevent cheating.

In this massive, globalized economy, we deal all over the world, every day, with people we do not know and with whom we will never deal again. For this system to work, the personalized checks and balances of the artisanal village are replaced by impersonal rules to prevent shirking, cheating, and defecting, including property rights, markets, contracts, banks, police, courts, information, Amazon reviews, standards, and so on.

Adam Smith’s second insight is that people can best judge their happiness.

Therefore, he argued that the most just mechanism for allocating resources is for self-interested people to make their own choices (rather than having governments make them).

This is also the most economically efficient mechanism. Smith defined the free market as competition based on price and quality alone, free of monopoly and other distortions.

This is not the same as laissez-faire economics because a philosophy of non-interference implies that the most powerful will be able to make rules that will benefit themselves.

US President Ronald Reagan’s statement, “The government is the problem”, is incorrect; markets need professional, independent bureaucrats to design good rules.

The shift from personalized regimes to impersonal exchange has created vast wealth, which is shared reasonably well.

North showed that this transition requires three things:

- New economic institutions (property rights, exchange, contracts) to encourage low-cost exchange.

- Political institutions to design and enact rules.

- Third-party enforcement of the rules.

We have sufficient knowledge about institutions to design them proficiently to get the economic outcomes we want.

Far more challenging are the political institutions that form and shepherd these rules and the mechanisms to enforce them.

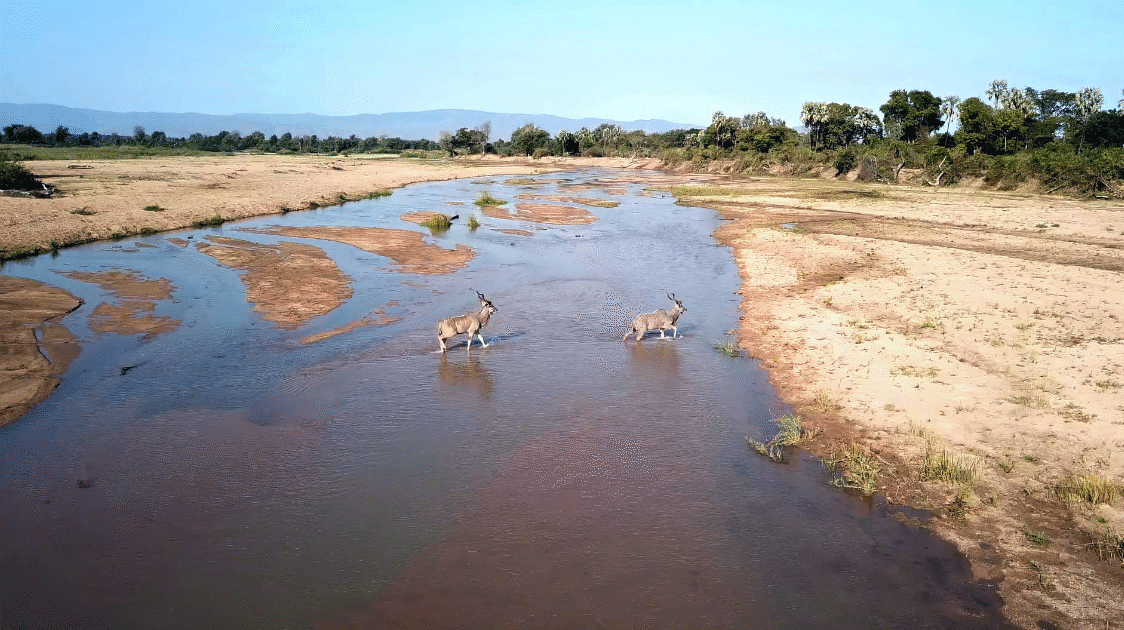

This includes the rules on wildlife ownership and trade, where permitting subsistence use, but preventing global trade, traps communities and wild resources in a pre-industrial economy that does not allow them to fulfil their comparative economic advantages.

Institutional Change as a Complex System.

New institutional economists such as Nobel Laureates Oliver Williamson and Douglass North provide a compelling four-level model to explain how institutions change.

Thus, economic rules occur within the bounds of the cultural norms of the society in question, leading society to organize itself in different ways and with different outcomes.

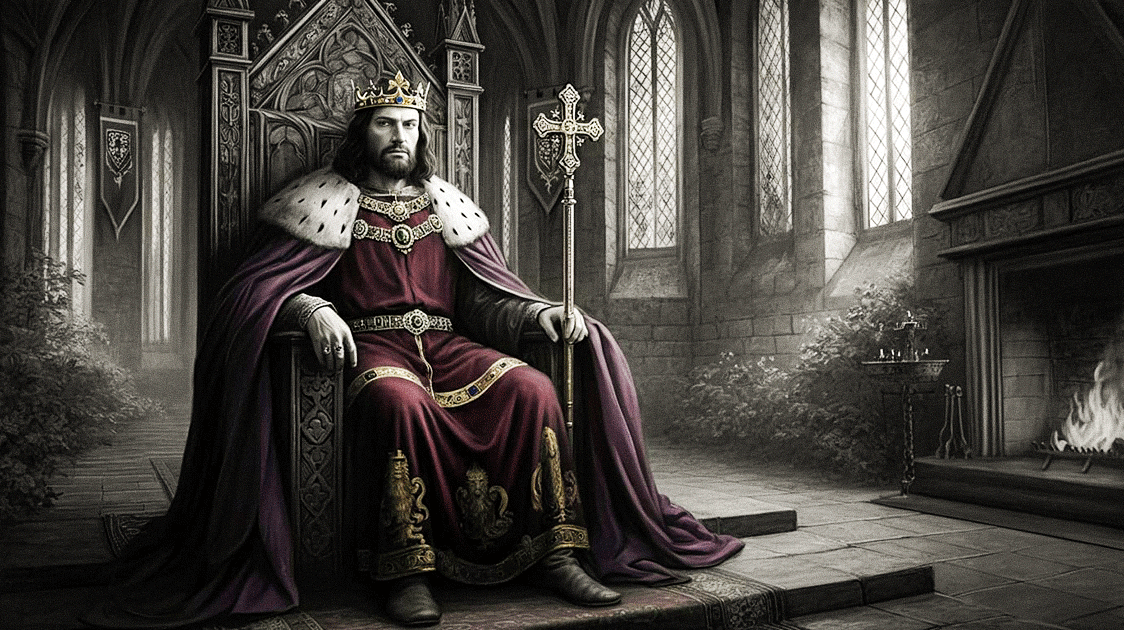

For example, the European Enlightenment challenged the divine right of kings as the primary societal authority and prompted ideas like individual rights and choice, constitutional governance, the separation of powers, and science (rather than religious dogma).

Consequently, age-old, personalized, neo-patrimonial practices like feudalism, serfdom, and peasantry, gave way to liberal democratic societies that valued individual rights, democratic processes, and the “rule of law”.

Thus, by 1700, an “Englishman’s home was his castle” and could no longer be violated at the whim of kings. These new rules led to new forms of organization, including elected parliaments, political parties, impersonal courts, and public limited companies, allowing the economic game to be played in different and far more productive ways.

With four interacting layers, the economy is a complex system, suggesting that we can get to the same endpoint in different ways.

For example, community conservation in much of Latin America arose from social movements encouraged by the Roman Catholic church, leading to stronger rights for local communities and, in some cases, better forest management.

By contrast, community wildlife management in southern Africa was conceptualized by enlightened bureaucrats, who then used successful pilot anti-poaching projects to encourage greater social acceptance of community-based approaches.

Policy change is assumed to be hierarchical, with sensible discussions at high levels resulting in new rules.

However, the low returns from donor investments in “policy reform” suggest hierarchical policy reform is often disappointing.

A more proactive mechanism is the “long-hook, short-hook” approach.

In essence, champions establish pilot projects, often working beyond the bounds of the current rules. If these pilot projects are successful, they can be used to change overlying cultural attitudes by demonstrating empirical success, making it easier to consolidate gains by transforming the rules.

The Rules for Free Markets are not Spontaneous; They are Designed.

Good economic institutions and policies are necessary to improve human livelihoods and the state of the planet. However, good institutions don’t evolve; they are designed, and herein lies the challenge.

Institutions such as democratic processes, property rights, and markets are created by people competing in political marketplaces, where outcomes are influenced by power, precedence, special interest, and enlightened technocrats.

Even so-called “free markets” are designed by people. The new institutions for good conservation outcomes will not evolve spontaneously. It is far more likely that old and failing institutions and the vested interests behind them will maintain themselves.

If we want new institutions, we will have to conceptualize and design them, fight for them through the four-level economic process described above, and develop mechanisms to protect and enforce these (enlightened) rules.

(Prof Brian Child is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida and the Life Through Wildlife Project director. His book, “Sustainable Governance of Wildlife and Community-Based Natural Resource Management”, is available on Amazon.)