The Conservation Funding Paradox

By Zig Mackintosh

Africa’s wilderness areas are critically underfunded. An IUCN assessment shows that available conservation funding across the continent meets only 10-20% of needs.

The most comprehensive study of conservation finance in Africa’s savannas, published in PNAS by Lindsey et al. in 2018, evaluated funding for 282 state-owned protected areas with lion populations.

They used the conservation needs of lions as a proxy for those of wildlife more generally; areas with lions usually have stable wildlife populations.

Their findings were disturbing.

Protected areas with lions require between USD 1,000 and USD 2,000 per sq km annually to function effectively.

The median funding they actually receive is around USD200 per square kilometer, with the total annual deficit across these areas ranging from USD0.9 to USD2.1 billion.

But things get even worse for the regions that aren’t in the media limelight or on the tourist map, yet have the greatest needs.

For example, in Zimbabwe, half of the country’s 22 protected areas with lions received less than one dollar per sq km in donor funding. The other half received a median of $272 per sq km.

Why is this?

The brand effect

Conservation funding essentially follows the same reasoning as consumer marketing.

Donors, whether individuals, foundations, or governments, fund what they recognize.

A national park with brand recognition, established tourism infrastructure, and a track record of media coverage is a safer bet for a grant-maker than an obscure wildlife management area in a country that rarely makes conservation headlines.

This makes good business sense. NGOs that depend on public donations need stories that resonate. Institutional donors need measurable outcomes tied to well-known places.

The result is a self-reinforcing cycle: funded parks produce data, which generate publications, which attract media coverage, which result in sweeping Netflix documentaries and drive more funding.

Underfunded parks produce little data, publish few papers, attract little press, and remain invisible to the funding pipeline and the public at large.

But even the glitziest of parks struggle with sufficient funding.

Kruger National Park, at the top of the funding totem pole, is still seriously underfunded, and when disaster strikes, its vulnerability is exposed.

Heavy rains in January 2026 caused severe flooding that washed away bridges, roads, and other essential infrastructure, resulting in the closure of camps and access routes.

Repair costs could exceed USD 45 million, far beyond the park’s budget.

With close to 80% of SANParks’ operating budget generated by tourism, damage to infrastructure at Kruger is both a logistical crisis and an existential threat to the whole organization’s ability to operate.

The Disney effect

Charismatic species feature high on the donor wish list.

A 2025 study published in PNAS by Guénard et al. examined nearly 14,600 conservation projects over 25 years. Their findings showed that the focus on charismatic species has produced severe taxonomic bias in funding allocation.

Almost a third of conservation funding went to non-threatened species, while 94% of threatened species received no dedicated support.

A companion analysis in BioScience concluded that ecosystems lacking charismatic taxa receive insufficient research attention and that the current approach reinforces the status quo of funding the most well-funded species.

Money follows fame, not need.

The fallout from this bizarre situation has been measured.

A 2021 study in Conservation Letters surveyed 516 protected areas and community conservation areas across Africa’s savannas and developed a Conservation Area Performance Index that combined data on budgets, management capacity, and threats.

The results showed that 82% of the sampled area was in a state of failure or deterioration.

A mere 10% were succeeding or recovering.

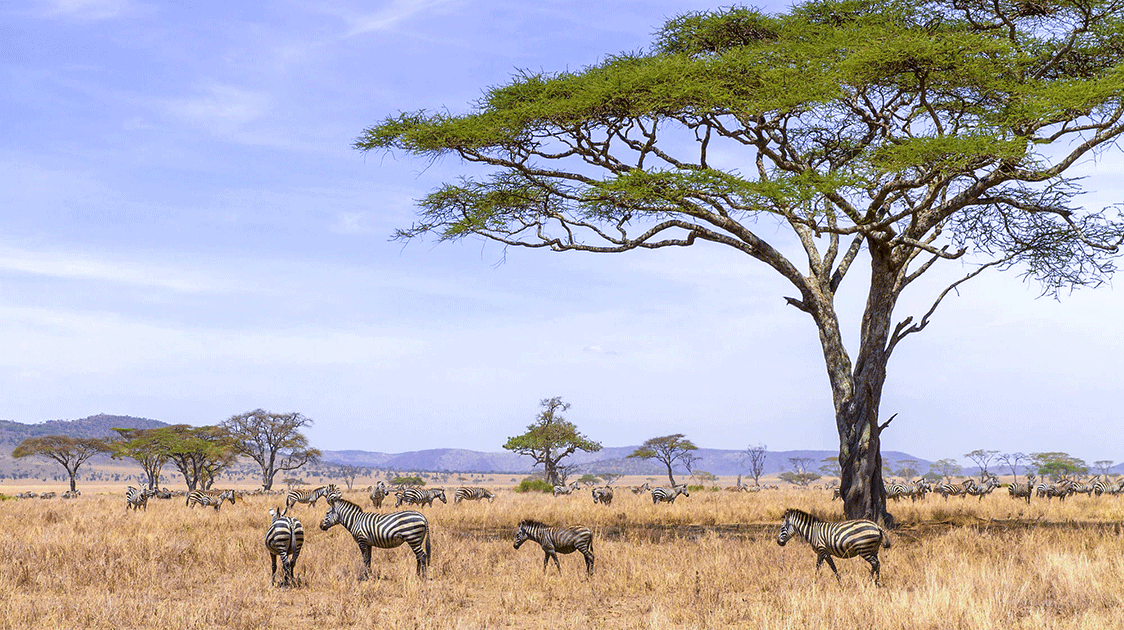

It’s not like there’s not enough space

The issue is not about designation. Several African countries have set aside large tracts of land for conservation.

Zambia 41%

Tanzania 32%

Botswana 29%

Mozambique 29%

Zimbabwe 28%

These figures far exceed global averages, but designation without funding is just paper shuffling while funding without rational allocation is a branding exercise.

Zambia offers a detailed case study. Lindsey et al.’s 2014 analysis of the country’s protected area network documented the scale of underperformance.

The Zambia Wildlife Authority (ZAWA) had resources of only $20 to $60 per sq km per year, against an estimated requirement of $358 to $455 per sq km for effective management.

ZAWA deployed one field staff member for every 196 sq km, compared to a regional average of one per 40 sq km.

In the country’s national parks, large-mammal biomass was 74% below estimated carrying capacity. In Game Management Areas, the figure was 94% below.

Meanwhile, 96.9% of Zambia’s photo-tourism revenue came from just four parks.

The remaining 15 national parks, covering roughly 32,000 sq km, attracted a total of 1,384 tourists during the year for which data were available, or 100 tourists per park per year, barely two per week.

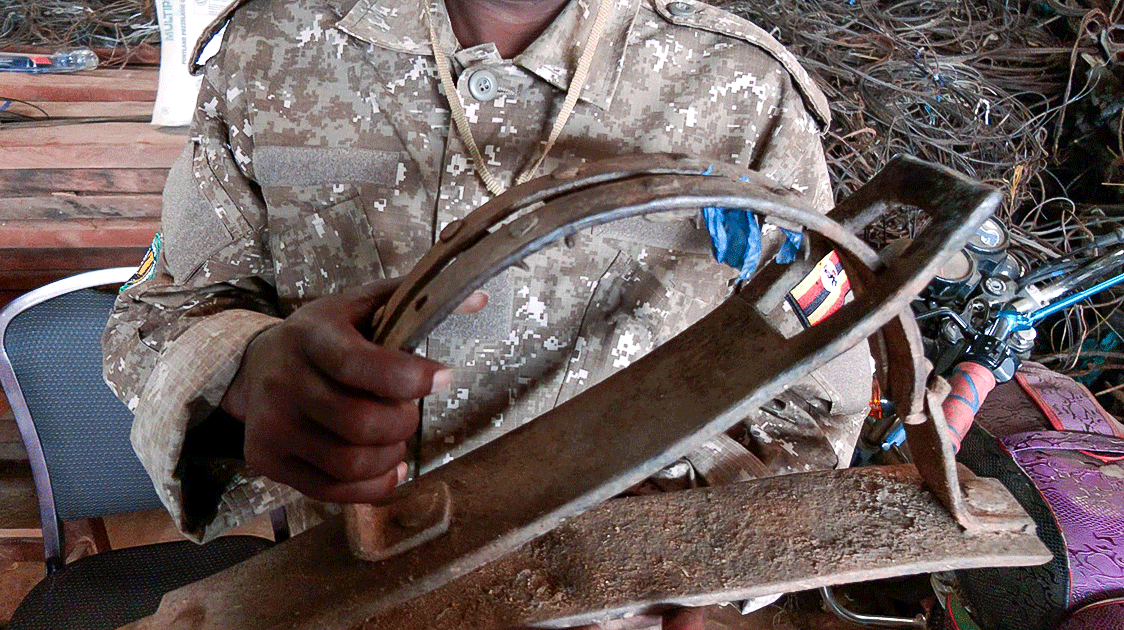

The anti-poaching dimension

This funding paradox has direct, measurable consequences on anti-poaching operations.

Poaching syndicates prefer to operate in the areas of least resistance.

“Fortress conservation”, concentrating resources in a small number of high-profile parks, pushes wildlife crime toward the margins, into the areas least equipped to react.

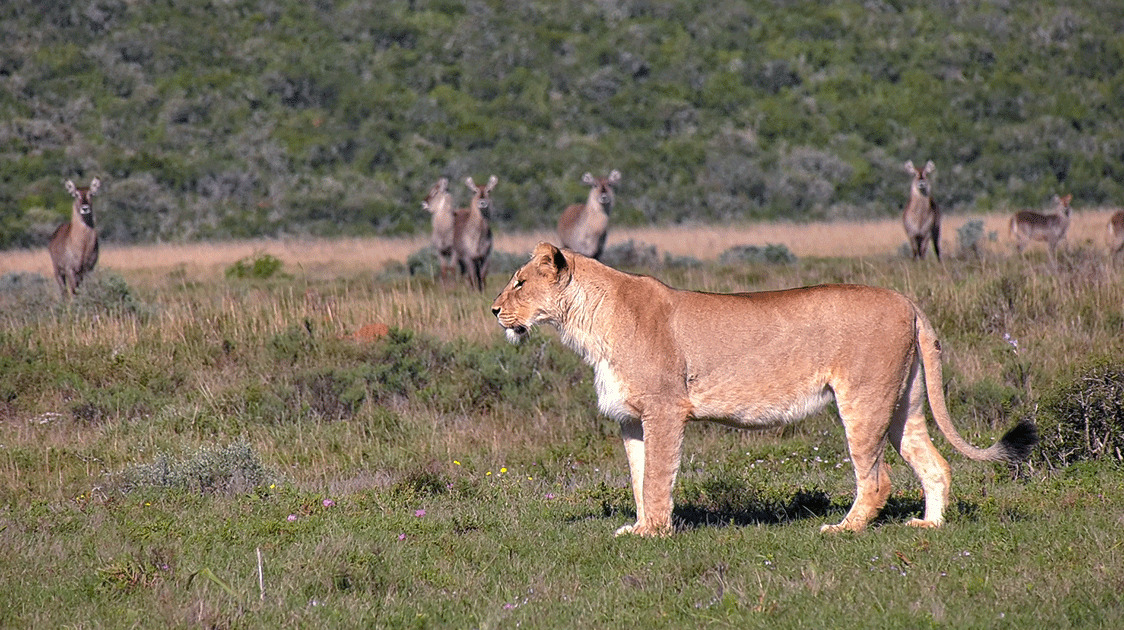

The most recent range-wide assessment of threats to African lion populations, published in 2025 by Funston, Lindsey and colleagues in Global Ecology and Conservation, surveyed 132 lion subpopulations across the continent.

The results reinforced this pattern.

The three most severe local threats were lack of funding, human encroachment, and loss of prey base.

Threat severity was highest in Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, and Ethiopia, areas where conservation funding is thinnest.

It was lowest in Rwanda, South Africa, and Namibia, the same countries where protected areas are best funded and most visible.

The study also found that perceived resource availability was lowest in Angola, Burkina Faso, Niger, South Sudan, Sudan, and Uganda.

These are not countries that lack wildlife; instead, they lack the brand recognition and institutional infrastructure to compete for international conservation funding.

The lions are there; the money is not.

Zambia’s data reinforces this.

In the areas studied by Lindsey et al. (2014), wildlife biomass was positively correlated with private sector or NGO investment.

Areas with such investment supported a mean biomass of 1,592 kilograms per sq km, while those without it supported just 233 kilograms per sq km, a sevenfold difference.

The link between funding and wildlife survival is not hypothetical; it’s math.

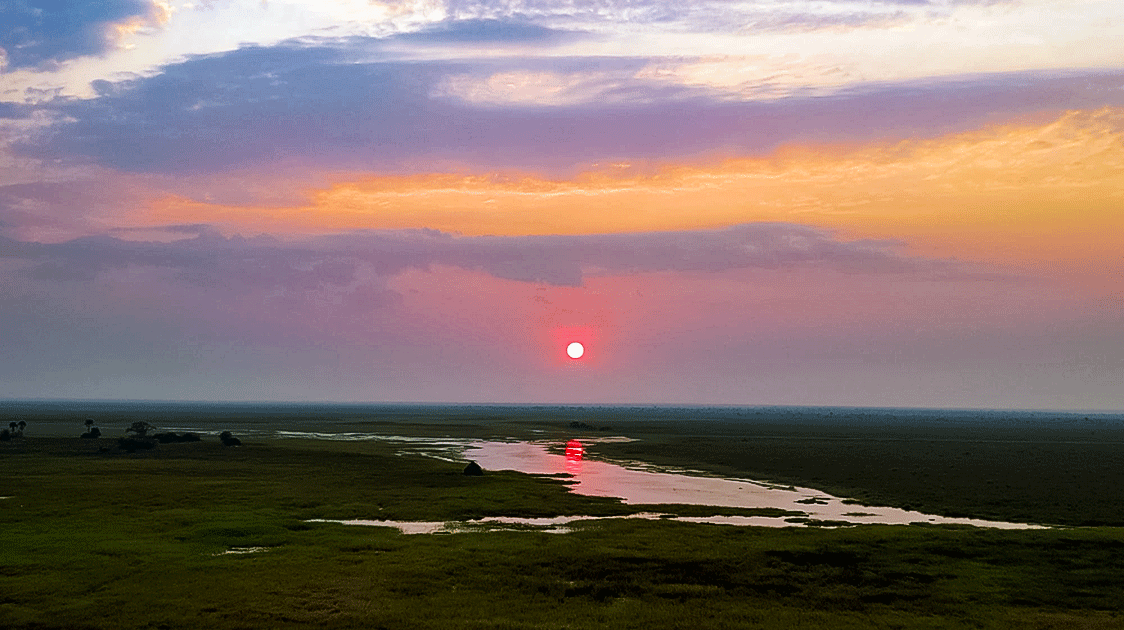

Models that redistribute

Not all conservation funding follows the charismatic model. Several approaches intentionally target failing or neglected areas, and the evidence suggests they work.

African Parks, the NGO that takes on management of protected areas in partnership with governments, has built its model around parks that others will not fund.

Their portfolio includes areas such as Zakouma in Chad, Liwonde in Malawi, and Liuwa Plains in Zambia, none of which would appear on a typical donor’s radar.

In Liuwa Plains, which African Parks has co-managed with the Zambian government since 2003, large-mammal biomass doubled from 966 to 1,921 kg per sq km over a decade.

That recovery is the direct product of sustained, adequate funding applied to an area that the mainstream funding system had bypassed.

A 2024 study published in PNAS examined the outcomes of African Parks’ management model across multiple sites and found that private management augmented both wildlife outcomes and tourism.

However, it also identified an unintended consequence: improved monitoring and enforcement in some areas increased the risk that armed groups would target civilians, a reminder that conservation funding operates within complex security environments rather than in isolation from them.

Namibia’s communal conservancy system offers a different model. Rather than concentrating resources in a few flagship parks, it distributes them across a network of community-managed conservancies.

The system has its own challenges. A 2025 review of community-based conserved areas in sub-Saharan Africa found persistent issues with unsustainable funding mechanisms, inequitable benefit-sharing, and weak law enforcement.

However, the architecture of distributed funding is fundamentally different from the fortress approach, and it has produced measurable conservation gains in areas that would otherwise have none.

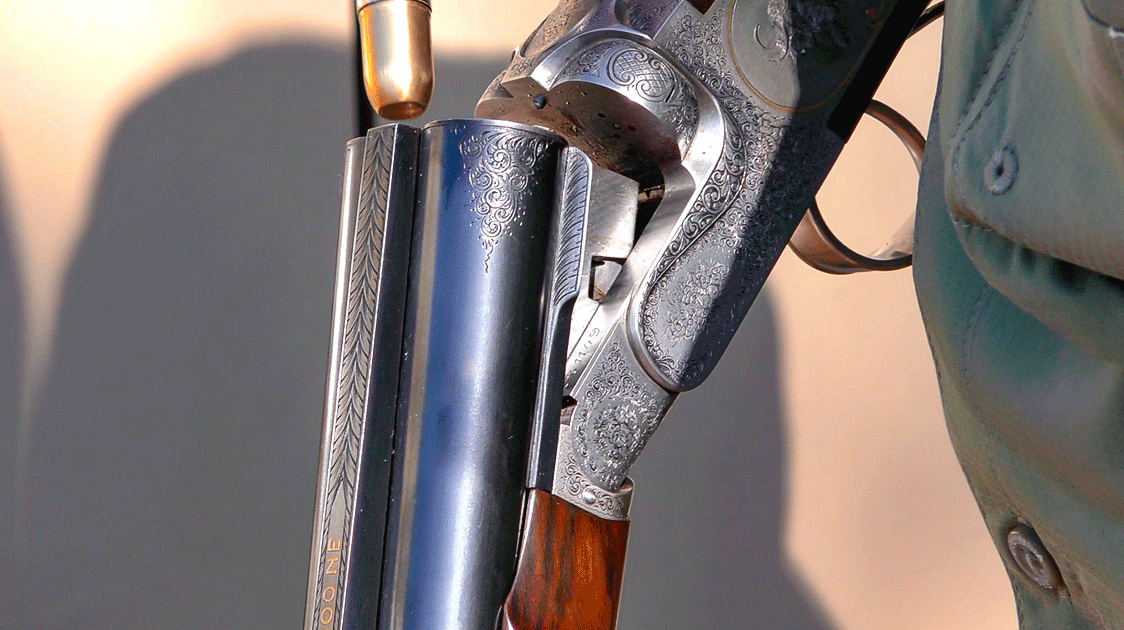

Safari hunting, whatever the animal rights activists may say, also generates operational funding for areas that would otherwise receive nothing.

In some countries, hunting concession revenue is the only income stream supporting the operation of remote wildlife management areas.

The economic reality is that many of Africa’s most important conservation areas cannot sustain themselves through photographic tourism alone, either because the infrastructure is not in place, the landscape does not lend itself to it, or the security situation makes tourism unviable.

Removing safari hunting from the equation without replacing the revenue it generates is a funding decision with conservation implications.

Much of the current conservation funding model across Africa depends on a handful of unstable pillars: tourism, short-term grants, and volatile donor contributions.

When tourism dips, revenue collapses. When donor priorities shift, funding dries up.

This boom-and-bust cycle undermines long-term planning and sustainable management.

Professor Patience Gandiwa, Director of International Conservation Affairs at the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (Zimparks), speaking on the challenges facing African protected area directors, stated plainly: the people running these parks are trained to do ecology, science, management, and conservation.

Instead, they spend 90% of their time looking for money and 10% doing the work.

At the 5th Global Conference on Biodiversity Finance in Cape Town, Inger Andersen, Executive Director of UNEP, advocated for decisive action, noting that financing mechanisms such as BIOFIN could be the engine to deliver on global conservation targets if countries commit and invest at scale.

Behind the damning statistics are people. Rangers working without adequate equipment, without backup, without decent, reliable pay.

We all know that Africa’s wilderness areas are worth funding for their biodiversity value, their role in climate regulation, and their potential to support rural economies.

But will governments, NGOs and the international conservation community step up to the plate and provide sufficient funding?

I don’t know if we should be holding our collective breath.

Zimbabwean native Zig Mackintosh has been involved in wildlife conservation and filmmaking for 40 years. Over the years, he has traveled to more than 30 countries, documenting various aspects of wildlife conservation. The sustainable use of natural resources as an essential conservation tool is a fundamental theme in the film productions with which he is associated.