The Busanga Plains: A Wetland Paradise Under Pressure

By Zig Mackintosh

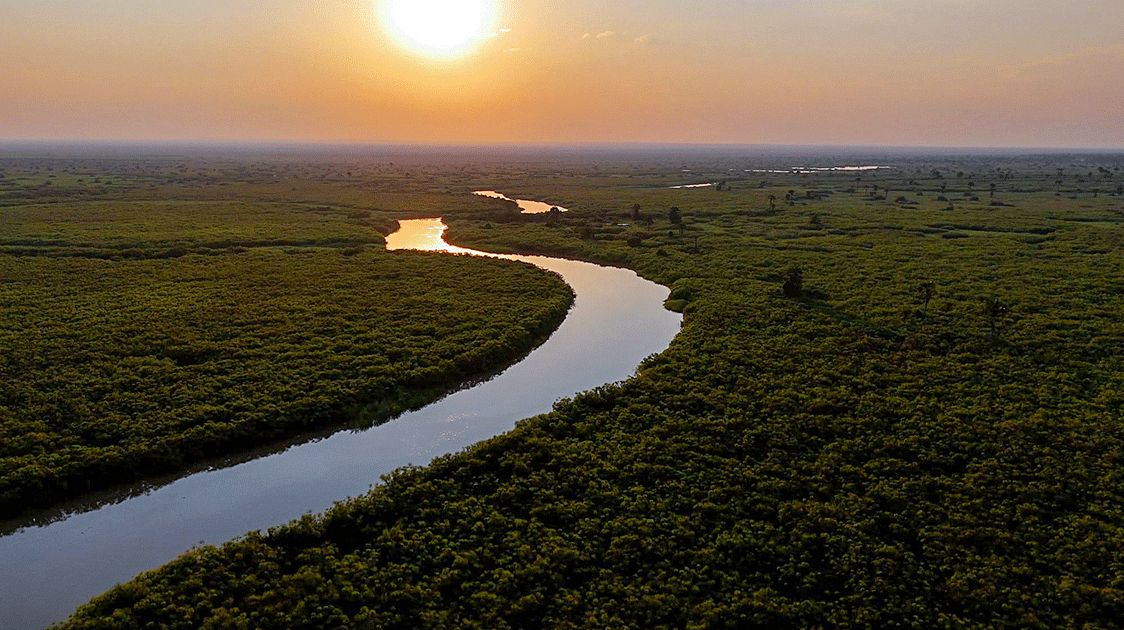

Saddling the Kafue National Park and the Lunga-Busanga Game Management Area (GMA) in Northern Zambia, the Busanga Plains span 720 square kilometers of seasonal floodplain.

Through ancient flood channels, the Lufupa River flows, creating one of Africa's great wetland wildernesses that supports extraordinary biodiversity.

From one season to the next, this vast wetland ecosystem undergoes a dramatic transformation.

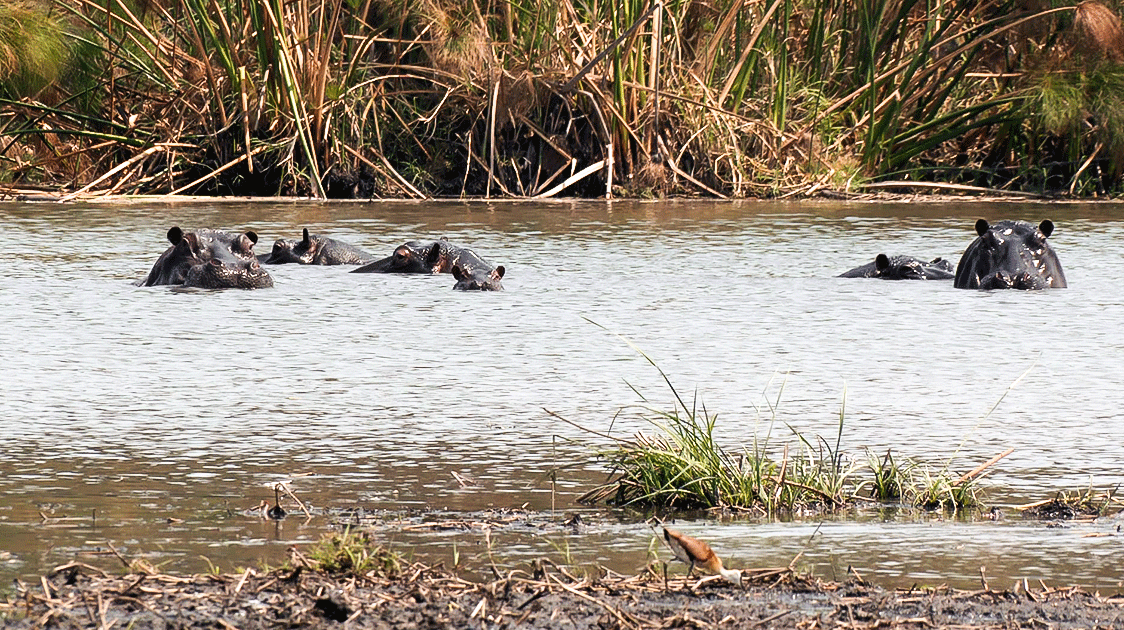

During the wet season, the plains flood, leaving a scattering of elevated islands. As the dry season approaches, the waters slowly recede, concentrating fish populations into an ever-narrowing network of channels.

The landscape transforms into open grassland. These seasonal transformations have shaped both the ecosystem and the human communities that have depended on its patterns for generations.

But there is an accelerating conservation crisis centered around its abundant fish populations.

The story of fish poaching in the Busanga Plains must be placed within a historical context.

Long before government conservation boundaries were drawn on maps, the Nkoya people and other local communities developed sophisticated fishing techniques that were adapted to the seasonal rhythms of the plains.

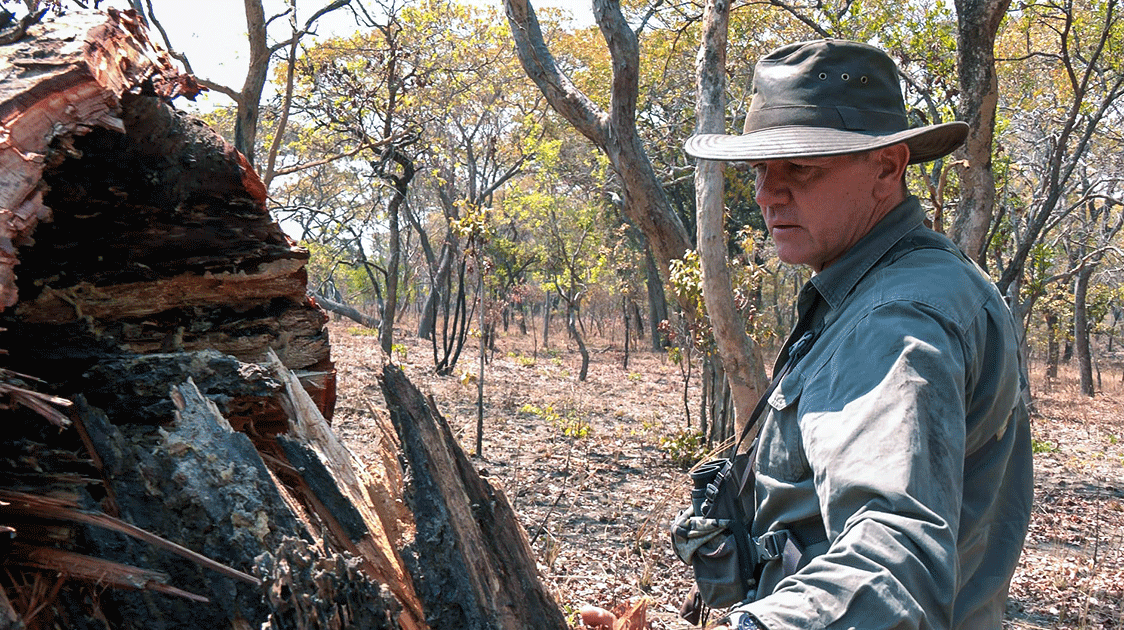

Fico Vidale, the current lessee of the Lunga-Busanga GMA bordering Kafue National Park, describes this legacy: "Before the National Park was established, the villagers had fishing weirs that they put over streams and floodplains on the Busanga plains."

These customary structures, placed where floodwaters recede and fish migrate back to their permanent rivers, represent generations of accumulated ecological knowledge.

When Kafue National Park was formally gazetted, the government relocated the traditional owners from their villages to the town of Mumbwa, outside the park boundaries. As these villagers had been dependent on fishing for generations, they reached an agreement whereby they retained seasonal fishing rights within the park.

This compromise, while acknowledging traditional rights, has created a complex management challenge. While subsistence fishing continues, commercial fish poaching has become a serious issue.

Unsustainable fishing practices, which utilize nets with mesh sizes that are too small, have a devastating impact on fish populations. The use of mosquito nets in breeding swamps captures juvenile fish, which are essential for population recovery.

"They're catching not just the breeding fish but also all the small fry that is our future fish," Vidale observes, noting that official breeding season closures prove ineffective during rainy seasons when enforcement presence is minimal.

The result is the systematic depletion of fish stocks, which form the foundation of aquatic food webs.

As Vidale notes, "these ecosystems are very delicate and once we lose them, it's very, very difficult to get them back to what they are."

The Zambian government, to mitigate the crisis, decided to limit the licensing of fishermen to 1,665.

To facilitate the identification of these fishermen by anti-poaching patrols from the air and on the ground, African Parks, which assumed management of Kafue in 2022, issued each of them a yellow shirt with their registration number in big writing on the back.

However, Vidale points out, this well-intentioned system has created unintended consequences: "People will find a way to even get around these methods. They think they have a license with that t-shirt and the number on it just to wander all over the place, and they use it as cover for their wildlife poaching activities as well."

This exploitation of the registration system highlights a fundamental challenge in conservation: striking a balance between legitimate traditional use and protection against commercial exploitation.

The numbered shirts, intended to provide accountability, have instead become tools for deception, allowing some individuals to operate with near impunity under the guise of authorized fishing.

The rainy season, when fish breed and disperse across the flooded plains, is precisely when patrol teams struggle most to operate.

Roads become impassable, vehicles bog down in mud, and the vast flooded plains make systematic patrols nearly impossible. All the while, the poachers move through the area in canoes, posing as legitimate fishermen setting extensive snare lines along riverbanks.

These extended hunting expeditions can last weeks, and once all the poached meat is dried, the poachers carry it back for sale in the village markets.

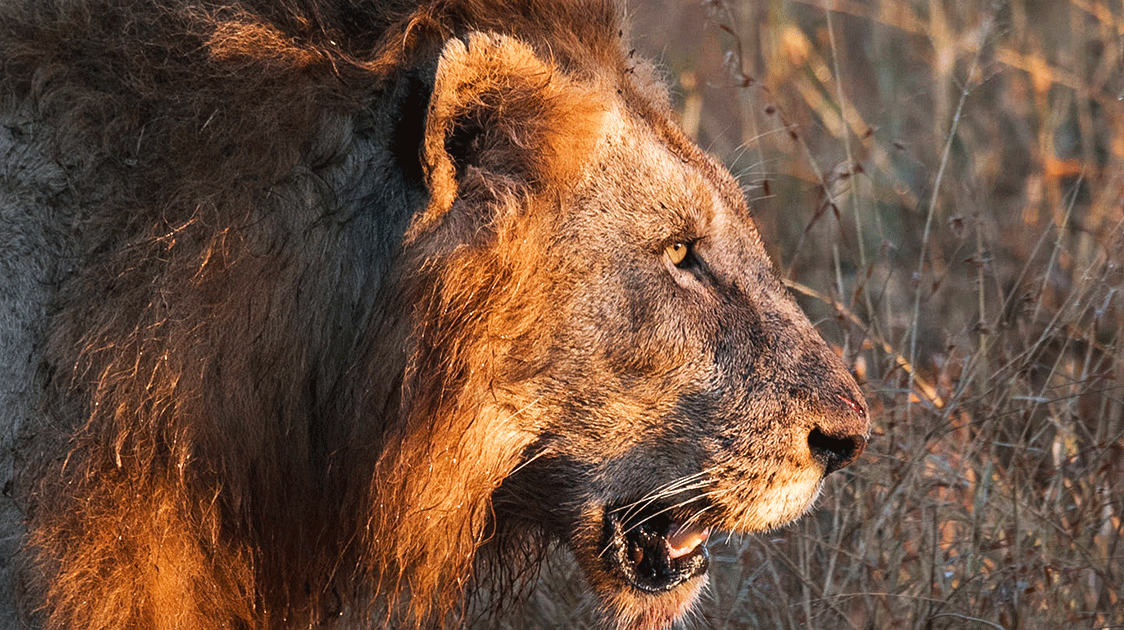

The methods used by poachers cause additional collateral damage. They often set the bush alight to rid lions of their cover in the grassland and to deter elephants. These fires, although they have some ecological benefits, can devastate wildlife when set too frequently or at the wrong times.

Additionally, upstream threats compound the problem. The most significant danger is pollution from mining on the Copperbelt upstream, which can poison the entire aquatic ecosystem that poachers and conservationists alike are fighting over.

The future of the Busanga Plains' aquatic ecosystems faces multiple uncertainties, but there are reasons for cautious optimism. Technological innovations in surveillance and enforcement continue to evolve.

Community engagement programs are slowly providing alternatives to poaching. Perhaps most importantly, there's growing recognition that conservation success requires addressing human needs alongside wildlife protection.

As Vidale notes from his years of experience, poachers "find ways"; they always have and will continue to do so.

But so do conservationists, communities, and ecosystems themselves.

The numbered shirts of registered fishermen may be an imperfect solution. Still, they represent something essential: an acknowledgement that the future of the Busanga Plains must include both its human and wild inhabitants.

The solutions won't come from enforcement alone, nor from community development in isolation, but from a careful weaving together of both, along with political support, much like the intricate channels that lace through the plains themselves, separate yet interconnected, each essential to the whole.

Vidale's work in the Lunga Busanga Game Management Area illustrates the complex realities facing conservation efforts across Africa, how to preserve irreplaceable ecosystems while addressing legitimate human needs.

Zimbabwean native Zig Mackintosh has been involved in wildlife conservation and filmmaking for 40 years. Over the years, he has traveled to more than 30 countries, documenting various aspects of wildlife conservation. The sustainable use of natural resources as an essential conservation tool is a fundamental theme in the film productions with which he is associated.