Still My Beating Heart: Killing Hummingbirds for Love

By Hanks Voice

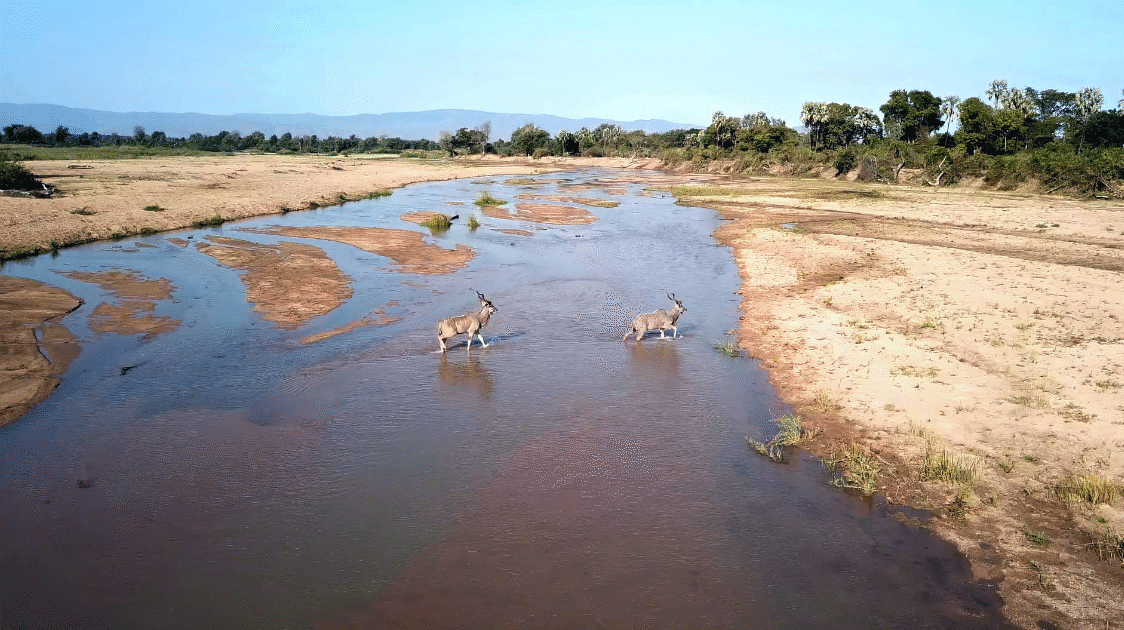

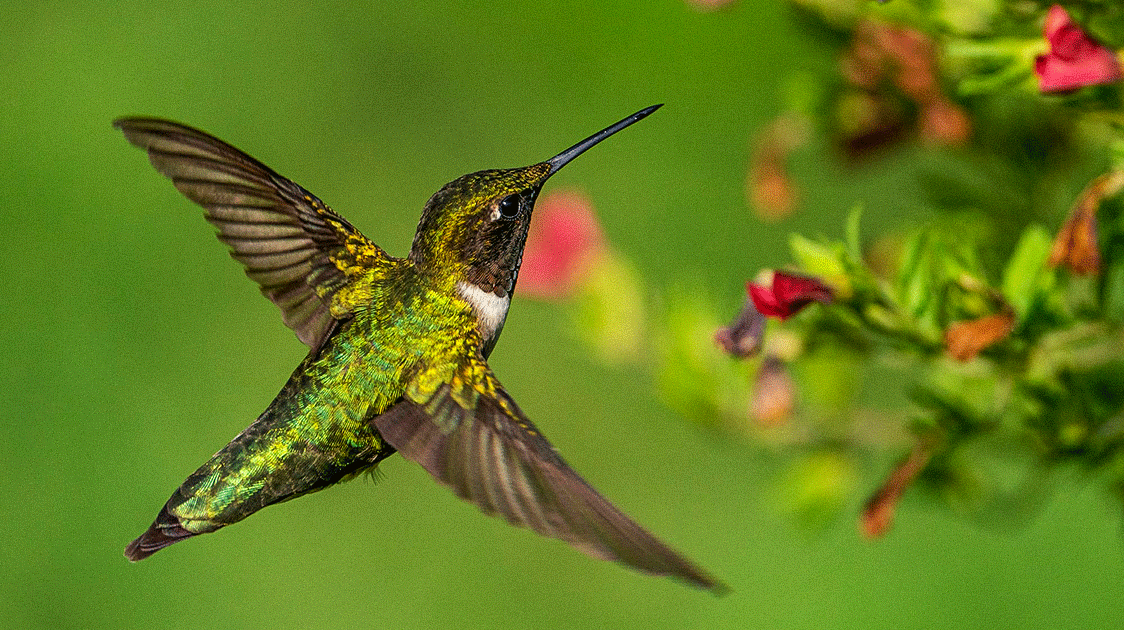

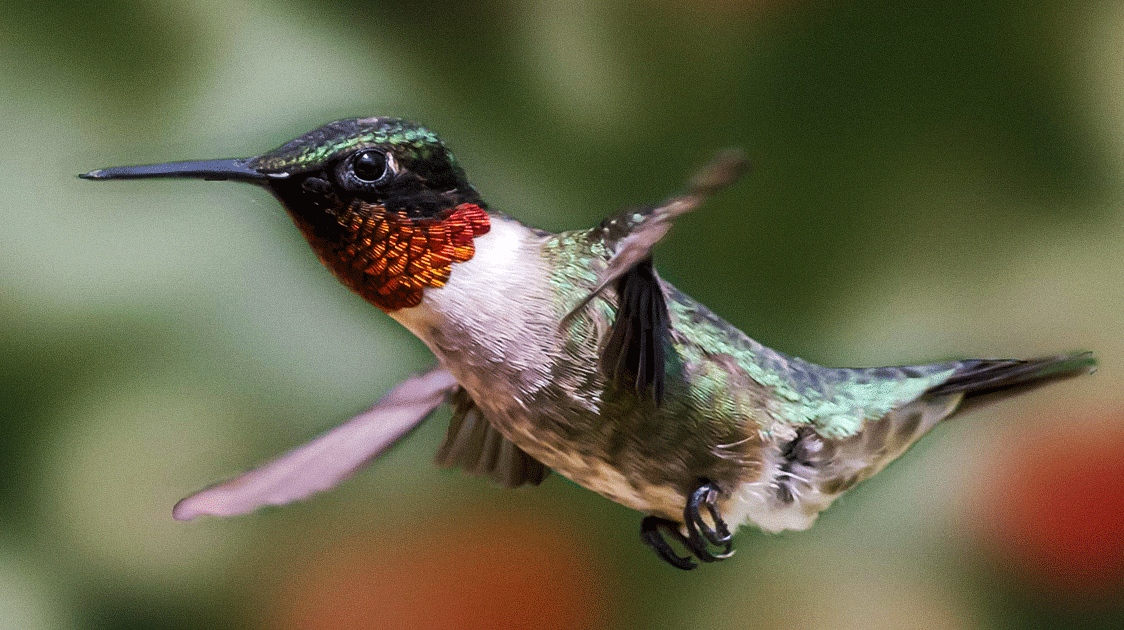

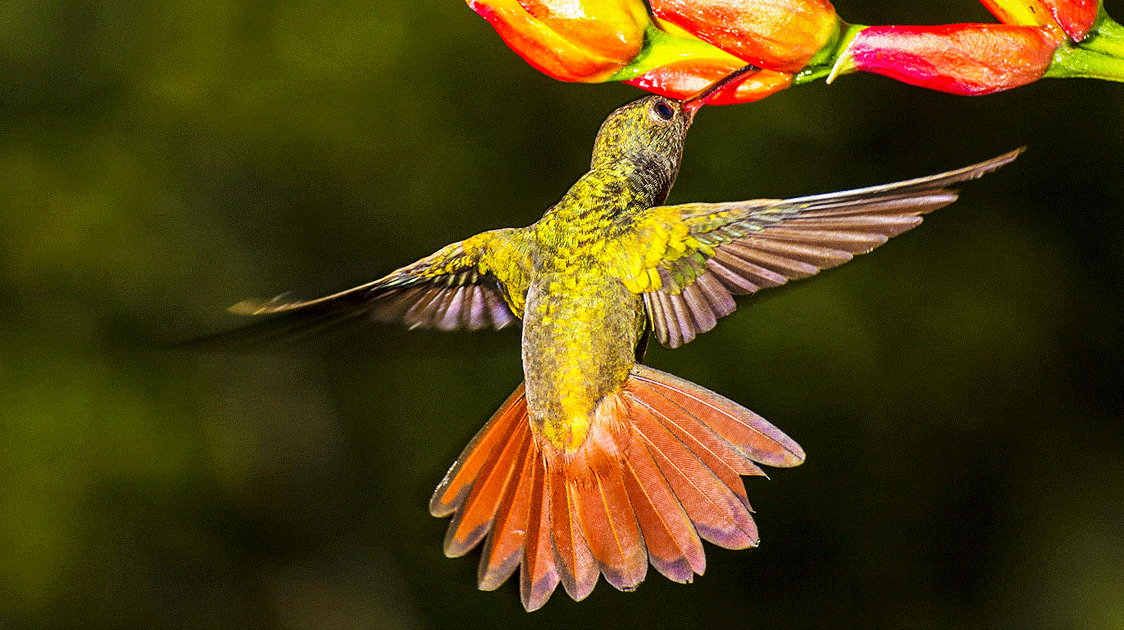

It's difficult to find someone not fascinated by and attracted to hummingbirds. They are universally alluring avian marvels that are highly recognizable, tiny in stature, capable of incredible, almost helicopter-like maneuvers in flight, and bejeweled with stunning iridescent plumage.

Sightings of them are coveted in the wild and also highly cherished in gardens and at nectar feeders.

Yet few of their admirers know about a deadly desire for hummingbirds – the illicit trade in their carcasses by those seeking love in their lives or enhanced vitality, similar to these energetic sprites.

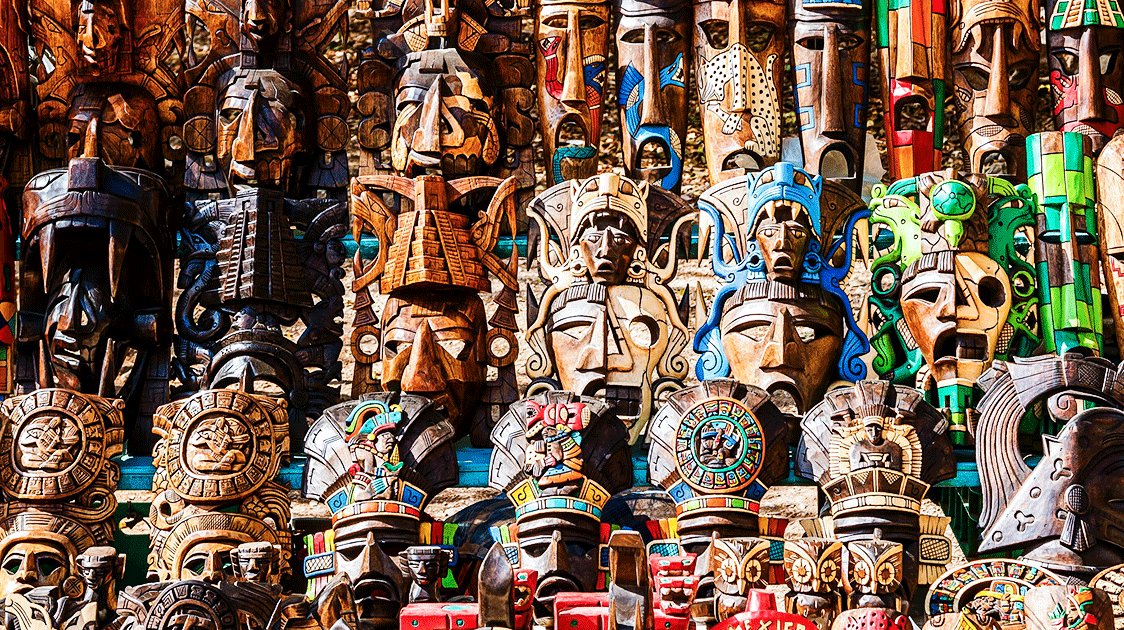

Hummingbirds have historically been powerfully symbolic for a variety of human cultures. The Aztecs of Mexico, for example, often depicted their god Huitzilopochtli as one, and warriors who died in battle or were sacrificed to him were believed to attain eternity in the bodies of hummingbirds.

Other indigenous groups throughout the Americas considered them healers who brought good luck, were messengers from the spirit world, and were symbols of love, attraction, positive energy, and blessings. Their probing of flowers to obtain sweet nectar, which facilitates life via pollination, was also understandably perceived as sexually suggestive.

What is a “Chuparosa” love charm?

Chuparosa (sometimes spelled with two r's) is a nickname for hummingbirds, translating literally to 'rose sucker'. It is also the name for a love charm made from these dainty little beauties.

It is a centuries-old tradition in Mexico that has spread to the USA in recent years. Illegal in both countries, it's a type of illicit wildlife trade about which much remains to be learned, quantified, and enforced.

How hummingbirds are killed and packaged

To make chuparosa love charms, the birds are first illegally killed. The methods are not fully known, but available information suggests that slingshots were traditionally used.

Currently, they are also dispatched with nets and shotguns, loaded with shells containing tiny pellets.

Their bodies are desiccated, usually in eviscerated form. They are then sealed in a paper tube, wrapped in thread, and placed in a bag with a prayer card called an oracione. Contemporary chuparosa charms often also have a Hecho En Mexico (Made in Mexico) sticker attached.

One presentation situates the body in a red paper tube, exposing the head whilst the body is hidden within a tassel of colorful satin strings. Typically, more expensive versions, referred to as vestida, are fully dressed in red.

Others are simply in gauze bags or absent packaging, other than some red thread through the eyes from which to hang the charm.

Most commonly, the prayer found in confiscated specimens implores the divine chuparosa, who gives and takes away nectar, gives life, and teaches women to love. The prayer also protects the possessor with powerful fluids and grants the possessor the ability to possess and enjoy any woman they want, be she maiden, married, or widowed.

When lovelorn souls buy a chuparosa, they pray to it, light a pure wax candle, and fervently hope their imploring is answered.

Where are charms sold and for how much?

It's often said you can't buy love, but how much does using a dead hummingbird to help you find it cost? A two-month survey at a large traditional Sonora market in Mexico City found 655 hummingbirds representing seven generally common species, offered for sale as chuparosa charms. Prices generally ranged from USD 3 to 8 apiece. In the USA, they are typically sold for USD 20 to 50.

Herbarias and botanicas specializing in traditional Mexican goods and remedies, and practitioners of the Santeria and Yoruba religions of the Caribbean, also buy and sell hummingbird carcasses. Usually just dried, with no fancy packaging, they are used as ingredients in various potions and remedies. Hummingbirds are also associated with Santa Muerte, the goddess of death, a popular figure with Mexican drug cartels.

Killing, utilizing, and selling hummingbirds is not a new practice, however. For centuries, they have been used in various ways. The Incas made textiles from their tiny, gaudy feathers, with even just one garment surely representing astounding numbers of them.

High society women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries used feathers and whole birds to decorate their hats. Millions were shipped to London and New York from South America during that era for such purposes. And hummingbird flesh, especially the heart muscle, is believed to have strong medicinal power.

Laws and enforcement (CITES, MBTA, Mexico)

Today, however, all hummingbirds are listed in Appendix II of CITES, which necessitates export permits to prove all specimens were legally acquired. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) also protects 31 species, prohibiting their killing, possession, and sale in the United States.

The Mexican federal endangered species protection law strictly protects 20 species and subspecies, although most are rare endemics not known to be targeted for chuparosas.

What do investigations reveal (2013–2021)?

Technically, killing and selling all hummingbirds in Mexico is forbidden, yet chuparosa charms are popular and widely available there. According to a US Fish and Wildlife Service report summarizing investigations into the trade from 2013 to 2021, they are offered for sale primarily in traditional shops catering to Mexican immigrant communities in the USA, such as Texas, New Mexico, and Minnesota.

Fifty-two separate investigations involving seizures of cross-border shipments and undercover operations following leads recovered 905 carcasses of 22 species, 18 of which (82%) are protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. All appeared to be killed and packaged in Mexico, but many originated from migratory USA populations.

Which species show up in seizures?

The much-loved and widely known Ruby-throated hummingbird was the most frequently identified at the species level. A tricky endeavor, as the plucking of feathers and severe desiccation in preparation of charms complicates identification, particularly for females with more drab, uniform plumage.

This species is a popular visitor to nectar feeders, with predictions of its arrival times throughout the USA in a highly anticipated press release each year. It nests entirely in the USA and is only in Mexico during the non-breeding season.

Two other species found in these seizures – the Allen's and rufous hummingbirds, also don't nest in Mexico.

Interestingly, one confiscated carcass was that of a marked Ruby-throated wearing a US Fish and Wildlife Service band, affixed by researchers on June 21, 2016, near Carbondale, Illinois. It was purchased as a chuparosa in Laredo, Texas, almost sixteen months later, on December 15, 2017.

Unfortunately, these seizures can only provide limited inferences. Most of the 22 species identified in this trade are widely distributed in semi-arid and highland habitats of central and northern Mexico.

According to limited published information, the majority are killed in the states surrounding Mexico City. Caution is advised, however, as that may simply be an artifact of where surveys have thus far been conducted.

Diverse packaging styles suggest that several different producers are involved in their retail. This assumption is also supported by the fact that various species were found in different states where seizures occurred.

As of 2022, five legal cases brought against sellers in the USA have resulted in sentences. All charged pleaded guilty to violating the MBTA, which could have resulted in prison time and fines up to USD 250,000.

However, their admission of guilt resulted in no prison time, 1 to 4 years' probation, fines from $100 to $5000, plus up to 6 months of home confinement and 212 hours of community service.

Hopefully, that community service involved something that benefitted hummingbirds.

Population and ecosystem impacts

The impacts of this trade on hummingbird populations are currently unknown. Since its actual extent is also unknown, it's tempting to think that the amount of trade is increasing with the current information available.

But truthfully, it can only be said that the awareness and amount of surveillance are expanding.

The levels recorded to date seem insufficient to have measurable or lasting effects on populations. The Ruby-throated Hummingbird is the most commonly confiscated species, and its populations remain robust.

However, intensive take in certain areas in Mexico could impact local populations, particularly if too many females and/or younger birds are killed. Because hummingbirds serve as pollinators for nearly 15% of plant species in the Americas, population losses can also have far-reaching ecosystem impacts.

The IUCN considers hummingbirds one of the most threatened bird groups in the world. Predicted temperature and rainfall increases in the coming decades could result in 89.8% of hummingbird species facing severe habitat reductions. It is especially concerning that some species are habitat or altitude-range-specific.

They face habitat loss on both their breeding and wintering grounds due to urban expansion and the conversion of forests to agriculture. Many countries they frequent are experiencing continued high deforestation rates.

In Mexico, currently established protected areas only cover around 12% of the distribution area of all species and 13% of threatened ones. Investigating the chuparosa charm trade is, therefore, not a high priority, as many conservation crises need to be attended to first, and limited resources exist to tackle pressing issues.

What should happen next - awareness, cooperation, alternatives

However, awareness may be growing, leading to public education efforts in Mexico to discourage the use of such charms. Investigators of this trade also suggest that enhanced collaboration between the USA and Mexico be encouraged.

Perhaps it should be made legal so that regulations can be created and monitoring enhanced?

Or possibly, since the many charms of living hummingbirds include gracing our forests and gardens, pollinating flowers in spectacularly beautiful ways, amazing us with their astounding migratory flights, and surprising us with the sudden buzzing of their hyperactive wings, alternatives that don't involve chuparosa charms can be adopted instead?