Property Rights and Economic Efficiency

By Prof Brian Child

I believe that the problems afflicting resource-dependent communities in forests and drylands originate from insecurity of person and property.

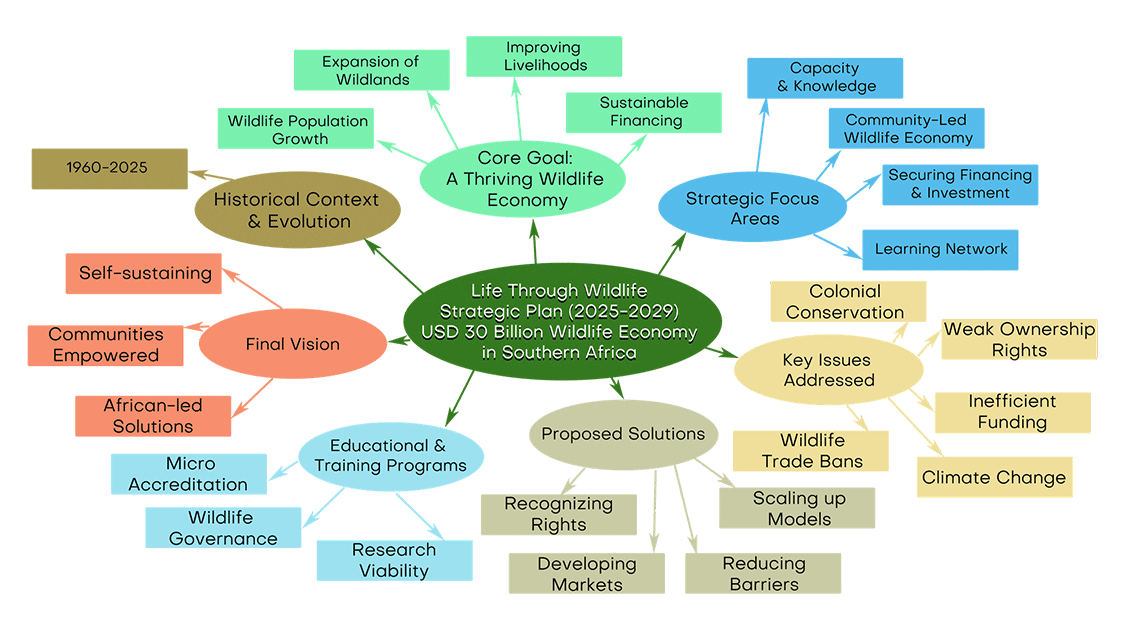

The institution of property in the context of the reinstitutionalization of ungoverned spaces through Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM), where property has four main purposes:

- The efficient allocation of resources as widely understood by economists.

- The equitable ownership of resources and the empowerment of the people who live with wild resources and bear their costs through entitling and community involvement.

- Security of person, as the foundation for rebuilding social capital, inclusive governance, and a sense of pride in one’s own resources.

- Clarifying the ownership of assets to improve opportunities for use and investment.

Property rights are central to economic efficiency, economic justice, and, I would argue, environmental and social sustainability. While the characteristics of assets are given, the rights over them are socially constructed.

To design new configurations of property that match the changing economic characteristics of wild resources, we need a better understanding of property in the context of wild resources and rural communities.

Indeed, the concept of proprietorship is a central component of the sustainable governance approach and CBNRM, along with price.

Proprietorship and price are suitors in the budding romance between economic principles and conservation.

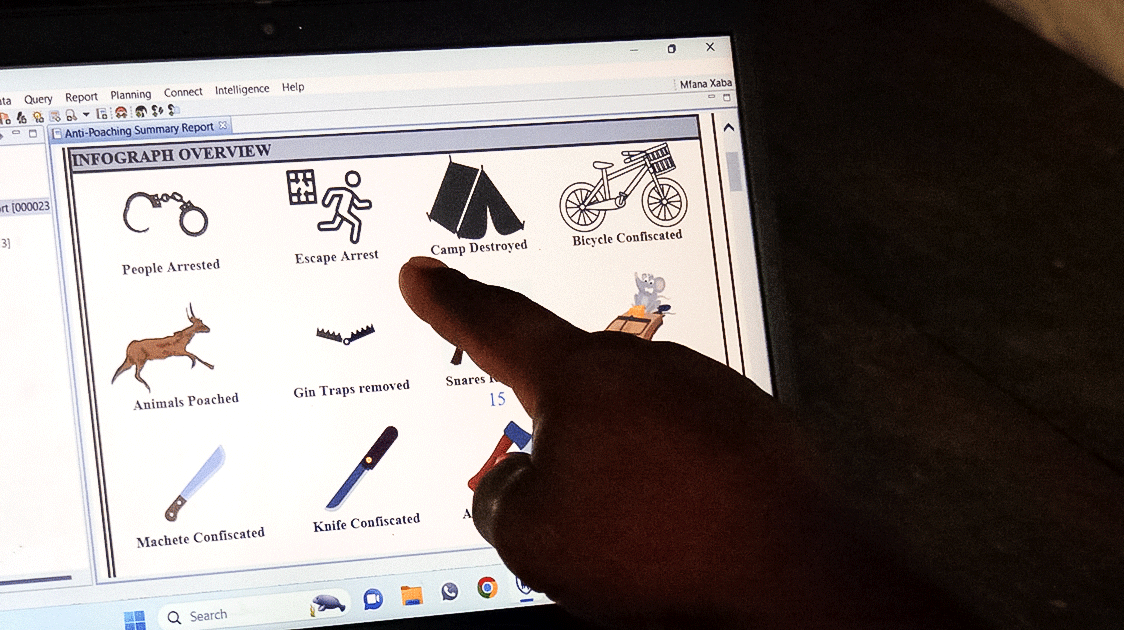

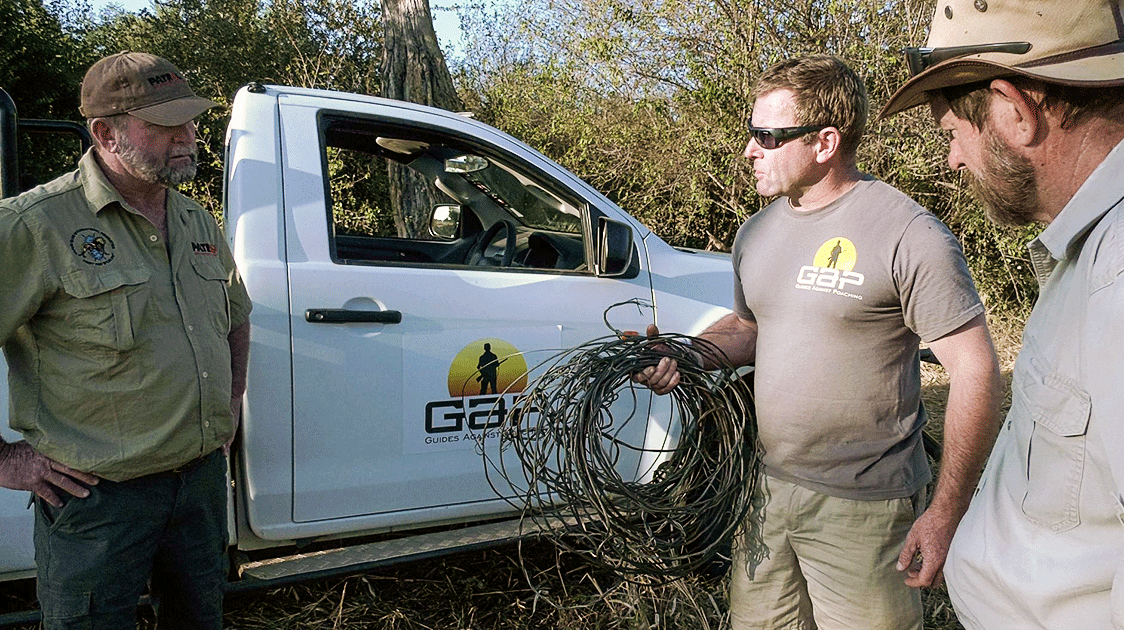

CBNRM is a rights-based approach, with rights serving as the foundation for effective economic and political governance and anti-poaching operations.

Ostrom and her colleagues have made immense contributions to the understanding of rights in the context of common-pool resources and collective action.

I only sketch out the big lines of these fascinating ideas. Readers are referred to the deeper conceptual analyses about property as a bundle of rights (Schlager & Ostrom, 1992), definitions of private, common-pool, and public goods (Randall, 1983; Hess & Ostrom, 2007), and the confusion between resources, rights, and owners (McKean, 2000; Hess & Ostrom, 2007).

Policy-makers tend to focus either on private goods and the market, or on the public regulation of goods not amenable to market allocation, with little attention given to the middle ground.

For goods in between, Ostrom demonstrated that collective management was not primitive, but remarkably sophisticated, and outperformed private or public solutions under certain conditions.

Practitioners already knew this intuitively, with Ostrom and others learning from long-lasting commons in the Swiss Alps, mountain villages in Japan, underground water management in California, medieval irrigation systems in Spain, irrigation systems in Sri Lanka and the Philippines, Turkish fisheries, and others.

The brief background on property rights provided below underpins an understanding of the governance and economics of wild resources.

The purpose of property

Property and the efficient allocation of resources

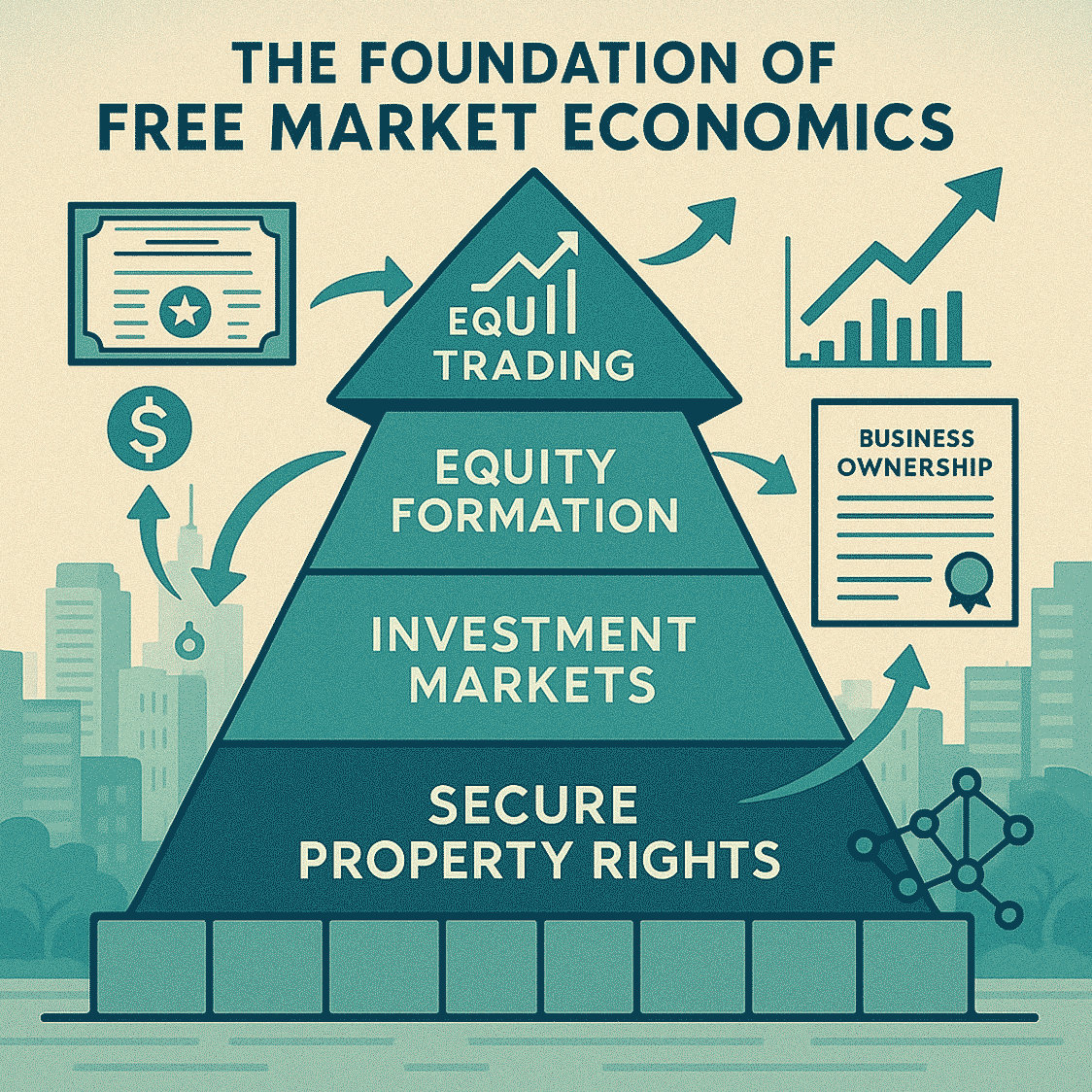

Private property is the basis of economic efficiency.

The classical economic argument is that clearly delineated property rights internalize the costs and benefits of land use to the owner, creating full accountability for action, which (combined with open, competitive, free markets) allocates resources to their highest valued uses.

Harold Demsetz (1967) argued that ‘a primary function of property rights is that of guiding incentives to achieve a greater internalization of externalities’ and that such property rights were primarily concerned with holding the owner fully accountable for his or her actions by controlling externalities.

Where property rights are clearly delineated, the costs and benefits of resource use are internalized to the decision-maker, resulting in the optimal allocation of resources (Coase, 1960).

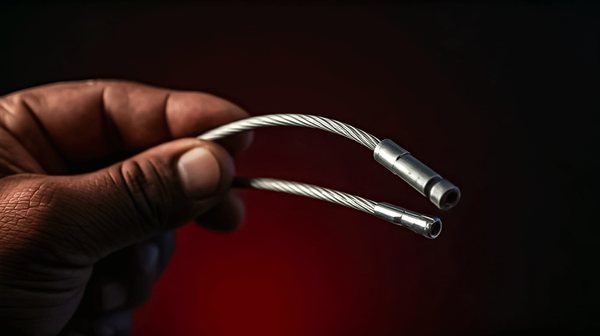

An important attribute of property is the right of exclusion.

This empowers the owner to exclude others from extracting resources without permission or payment, and prevents people who have not contributed from free-riding and reaping the rewards of the owner’s efforts.

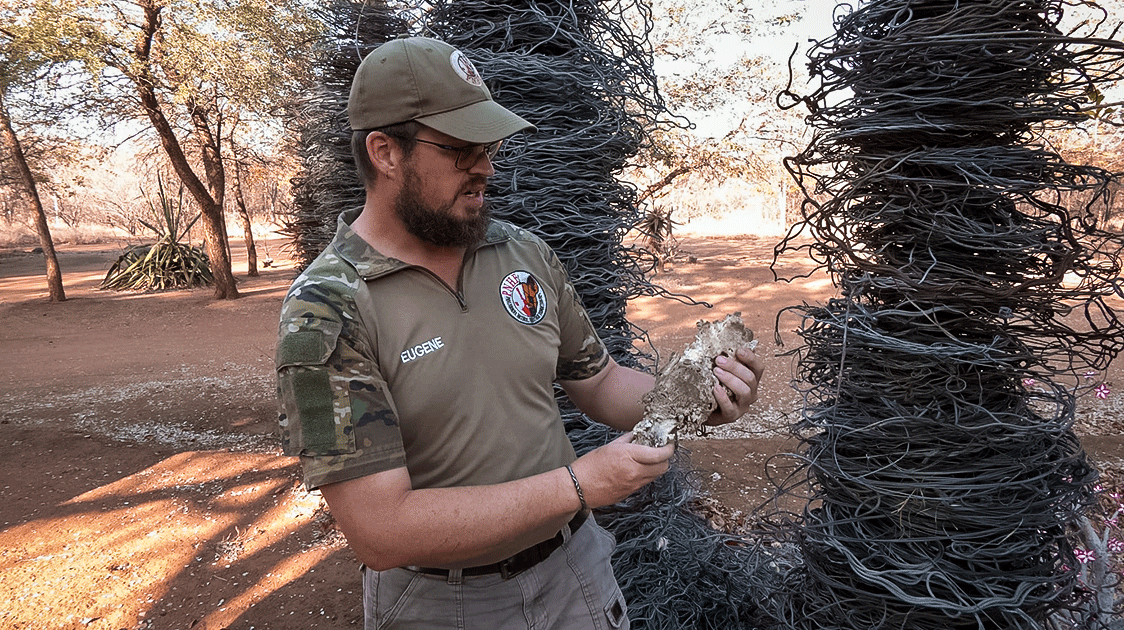

In the imperfect real world, we nonetheless need to design new forms of property rights for fugitive and complex natural resources that internalize costs and benefits, and exclude free-riding to replace the current institutions that are crude, entrenched, and inadequate.

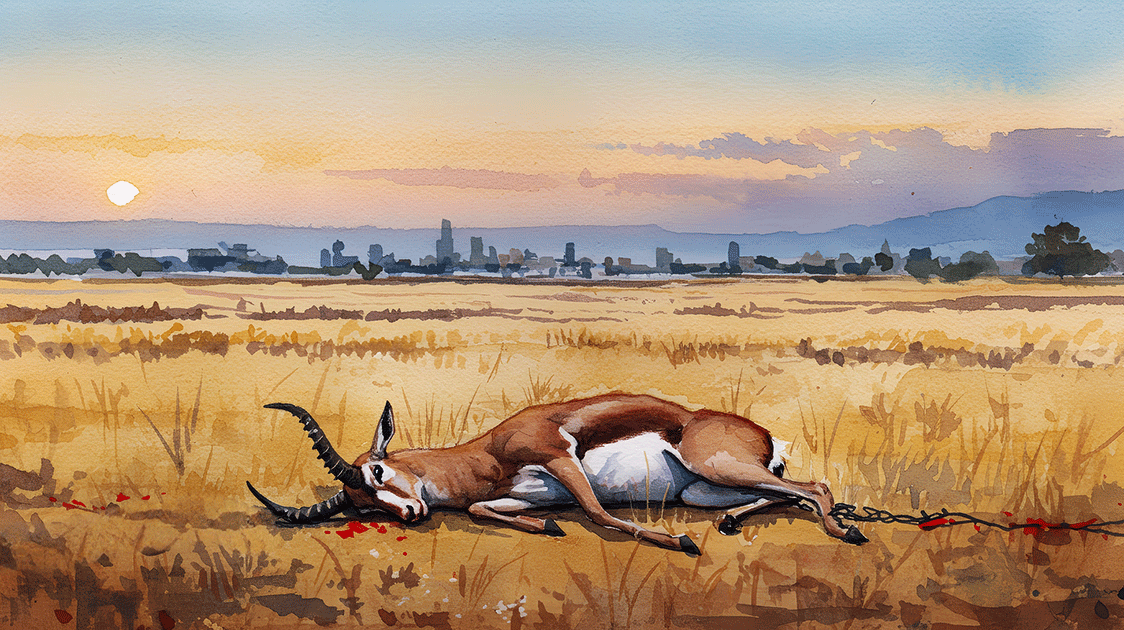

Incomplete property rights and the tragedy of the commons

The importance of property for resource allocation is best illustrated by observing what happens where property rights are absent or incomplete.

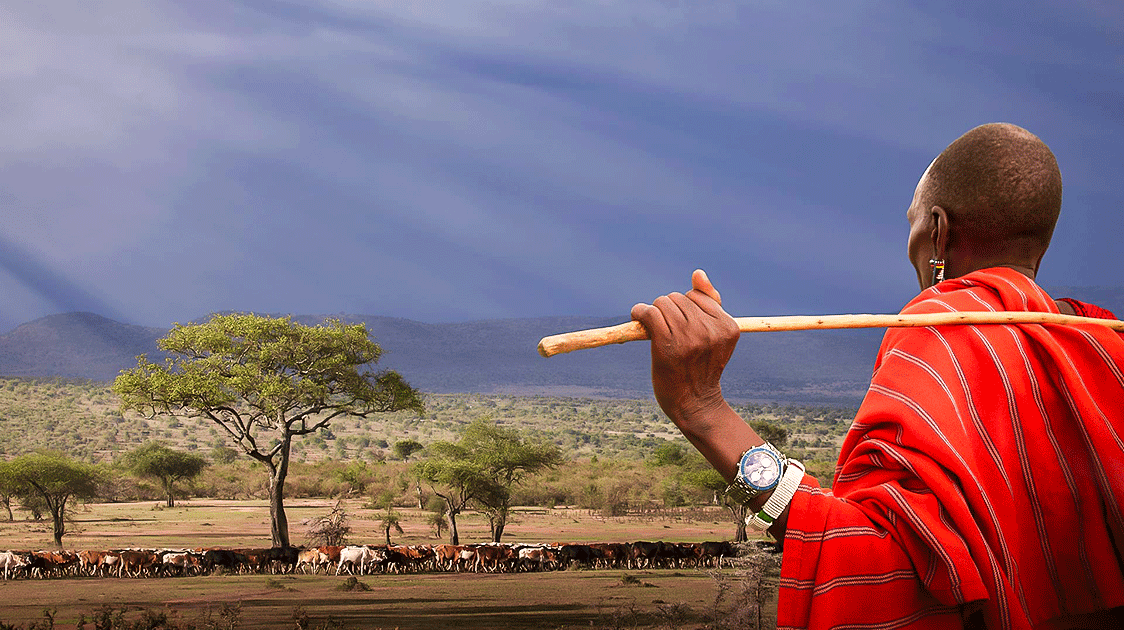

The classic example is Garrett Hardin’s tragedy of the commons, where the individual cattle herder reaps the benefits of his livestock but externalizes the costs of over-grazing to the rest of society: the rational herdsman concludes that the only sensible course for him to pursue is to add another animal to his herd.

And another; and another …

But this is the conclusion reached by each and every rational herdsman sharing a commons.

Therein is the tragedy.

Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit – in a world that is limited.

Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons.

Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.

The economic logic of Hardin’s tragedy of the commons applies widely to the problem of ungoverned spaces.

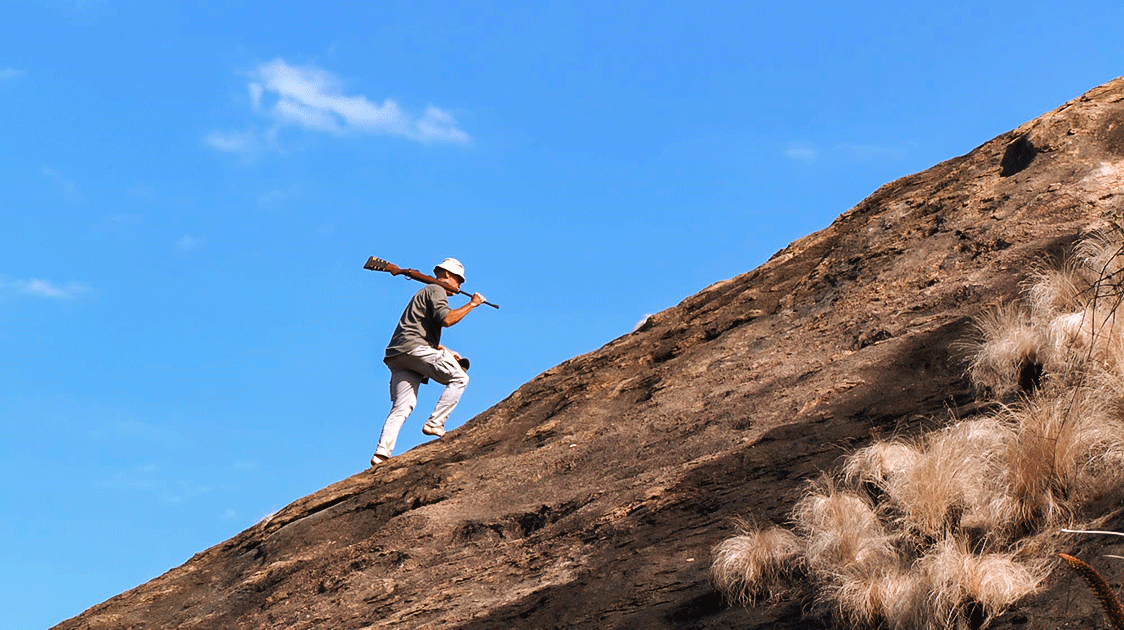

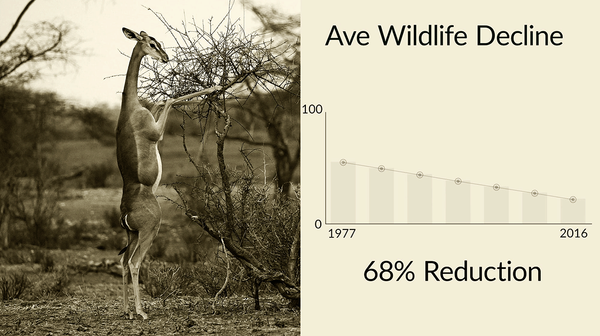

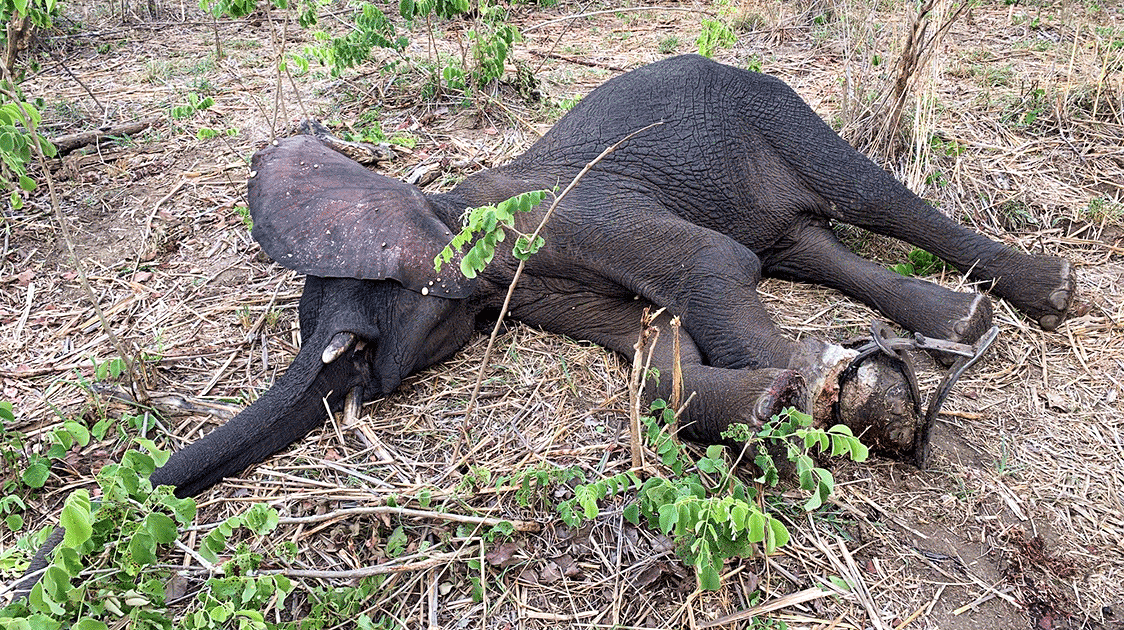

Each rational individual maximizes his or her private gain by adding one more animal, cutting one more tree, or hunting more bushmeat, one of the poaching threats.

The same conclusion is reached by all the people sharing the land, who privatize benefits while ignoring the social costs of their actions, inexorably degrading resources to the detriment of all.

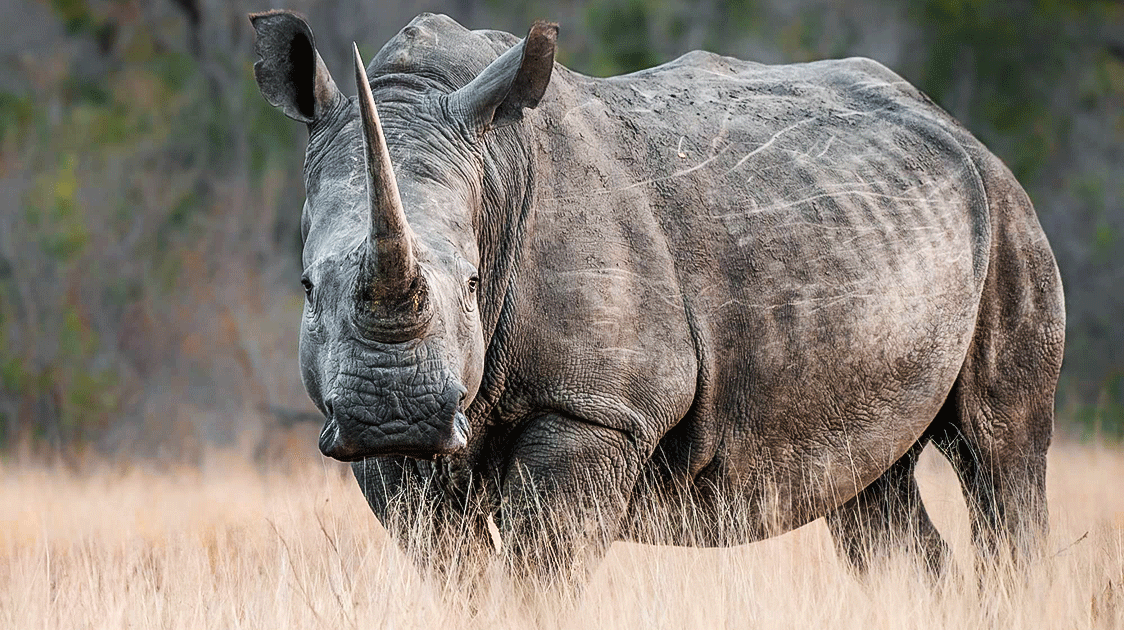

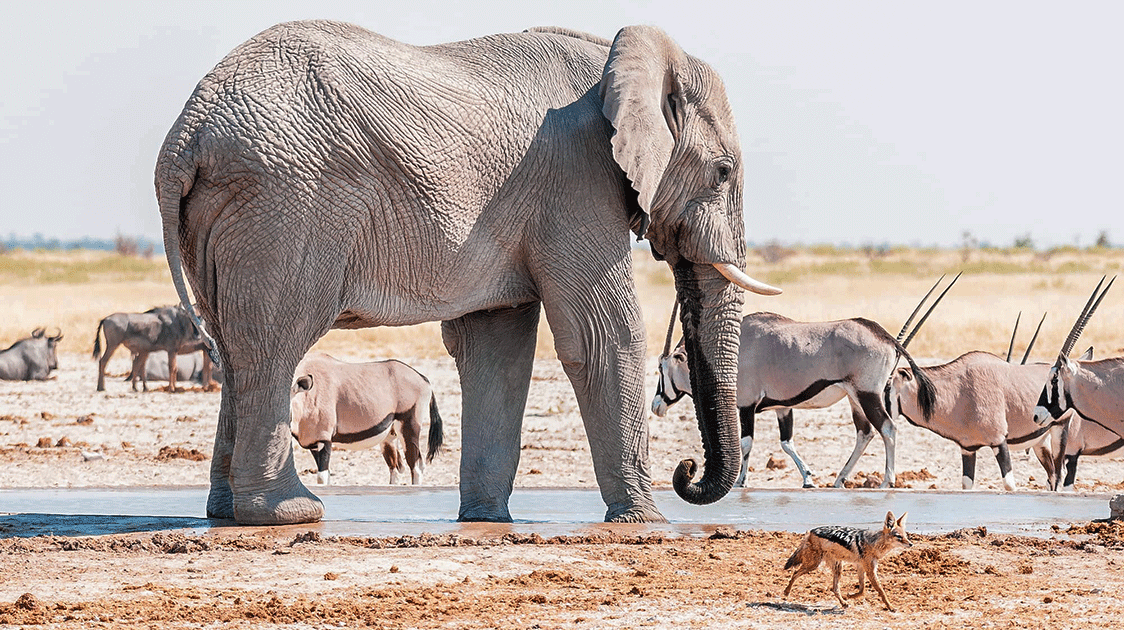

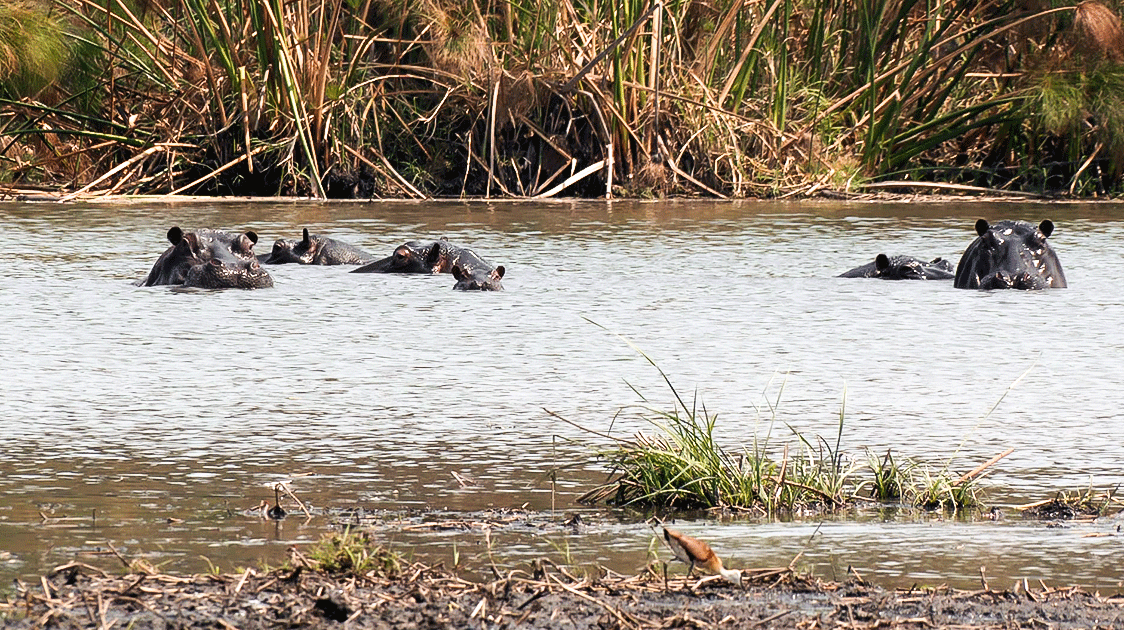

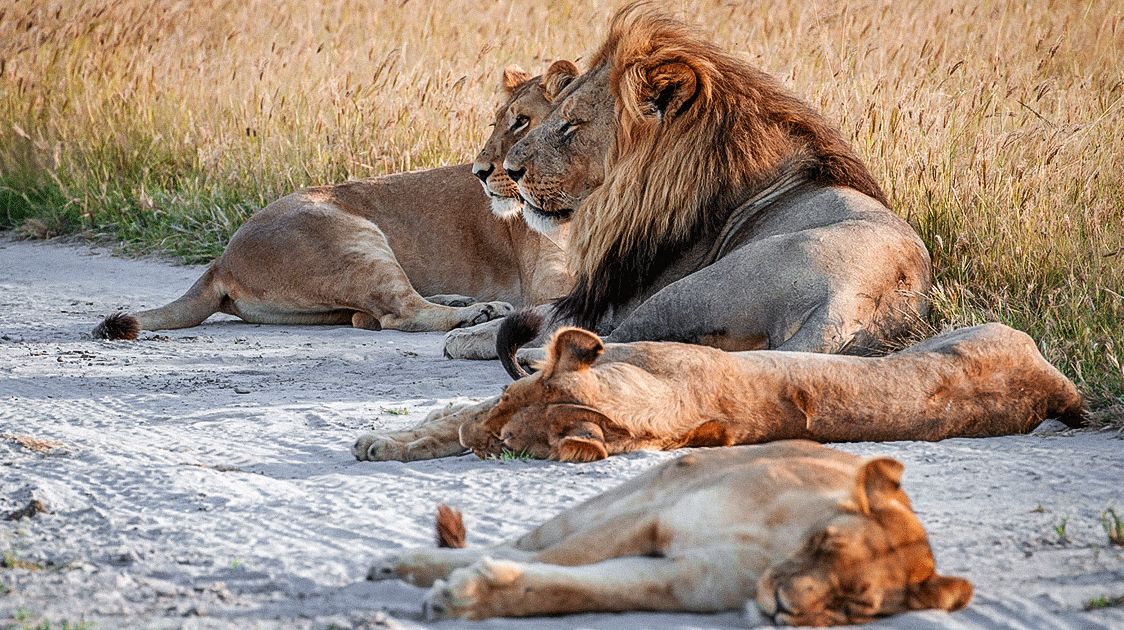

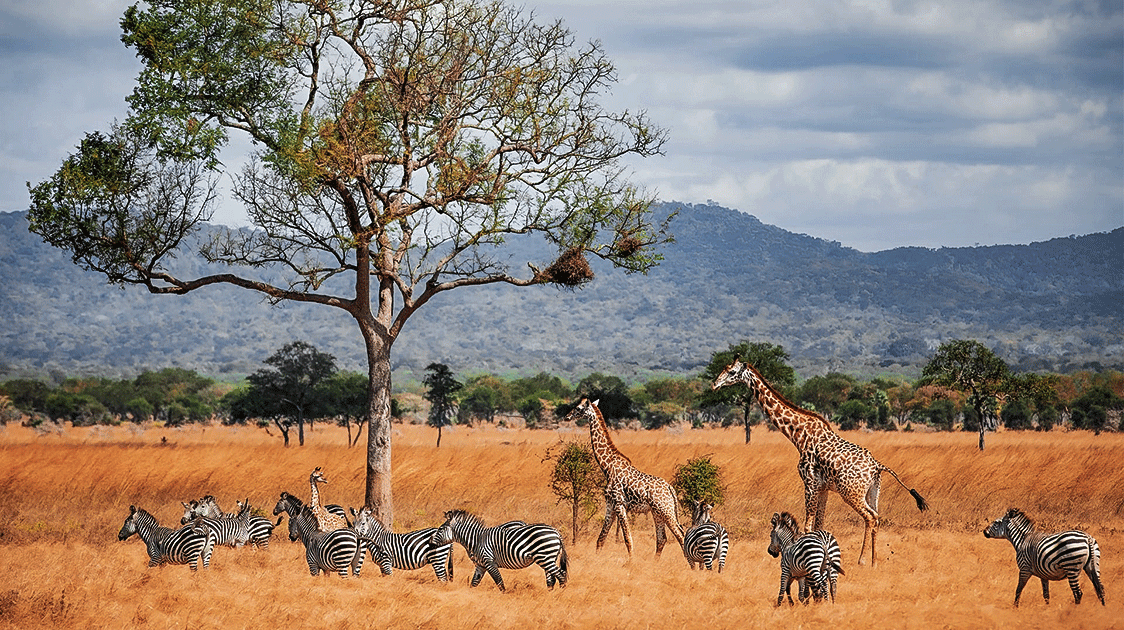

A similar argument applies to land use trade-offs between wild and domestic species.

If a person owns their livestock but does not own wildlife, endangered species (which is the property of all), they will increase their livestock until the wildlife has been wholly replaced.

The differential ownership of wild and domestic species means that the decisions made by individuals diverge from the best interests of society.

These are market failures, caused by incomplete or differential property regimes.

In these examples, individuals privatize the benefits of the cattle they own, but externalize the costs of unowned resources to society, be these overgrazed rangelands or the replacement of wildlife.

Economic efficiency is most likely where private goods are bought and sold in free markets, and where complete property rights internalize all costs and benefits.

In imperfect markets, however, prices are distorted by several factors, including incomplete property rights, externalities, asymmetric or incomplete information, noncompetitive or rigged markets, and other factors, resulting in resources being allocated inefficiently.

Fugitive, complex wild resources are particularly vulnerable to these imperfections, so private action does not contribute to the social good in the way Adam Smith anticipated, resulting in widespread overuse or under-supply of environmental goods.

Under-supply is associated with public goods, such as clean air, national radio, or national parks, which are consumed without contributing to their costs, resulting in ‘free-riding’ and less of these goods than we would ideally want.

Partial or asymmetric property rights are also highly problematic.

For example, weak institutions enabled colonial and later regimes to plunder raw materials, obtain cheap labour, and maintain political control at a low cost through indirect rule (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012).

Likewise, rural areas and wild resources are still exploited by the modern urban or global economy because weak property rights allow the latter to acquire these resources (i.e., privatize them) cheaply, with few requirements for reinvestment.

This allows for excessive rents, profits, or power that encourages the winners to maintain the status quo.

(Prof Brian Child is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida and the Life Through Wildlife Project director. His book, “Sustainable Governance of Wildlife and Community-Based Natural Resource Management”, is available on Amazon.)