Property and Equity

By Prof Brian Child

Economic efficiency results from clearly defined property rights and exchange in free markets and is independent of who owns the resources. Nonetheless, Coase (1960) and others acknowledge that the question of who owns the resources is also important.

Ignoring these distributional issues gives free market economics a bad name, especially as property regimes and markets are often defined by the rich and powerful to benefit themselves (Stiglitz, 2002).

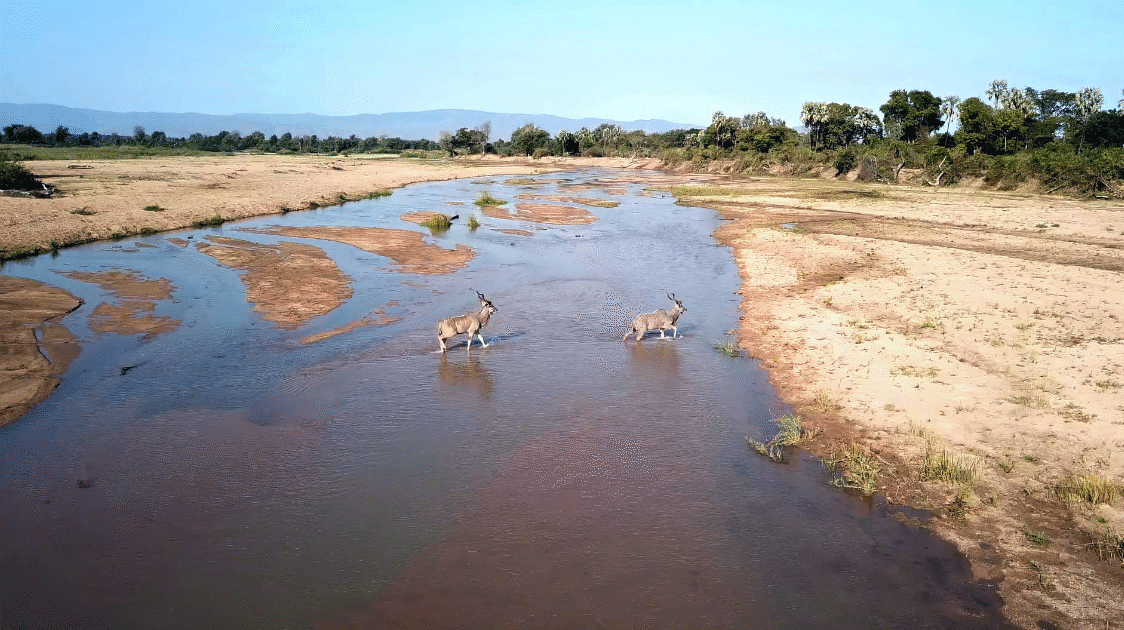

Thus, CBNRM seeks stronger property rights (1) to create wealth through the efficient allocation of wild resources, but also (2) to ensure that wildlife and the wealth it generates are owned by the communities who live with it.

Property rights also empower communities by providing legal protection against resource extraction and give communities the same incentives to protect ‘their’ wild resources as they have for domestic crops and animals.

Property, security, and inclusive governance

Property rights are usually discussed in the context of economic efficiency, where there is a broad consensus about their importance. However, an equally fundamental (and political) purpose of property is its guaranty of freedom (Hayek, 1944).

Security of person and property is a necessary condition for inclusive governance, allowing ordinary people to engage politically without fear of retribution.

In feudal systems, it is difficult for ordinary people, or ‘subjects’, to challenge the power of lords or chiefs without putting at risk their property or freedom.

Property rights are particularly important for the poor and disenfranchised (Bethell, 1998).

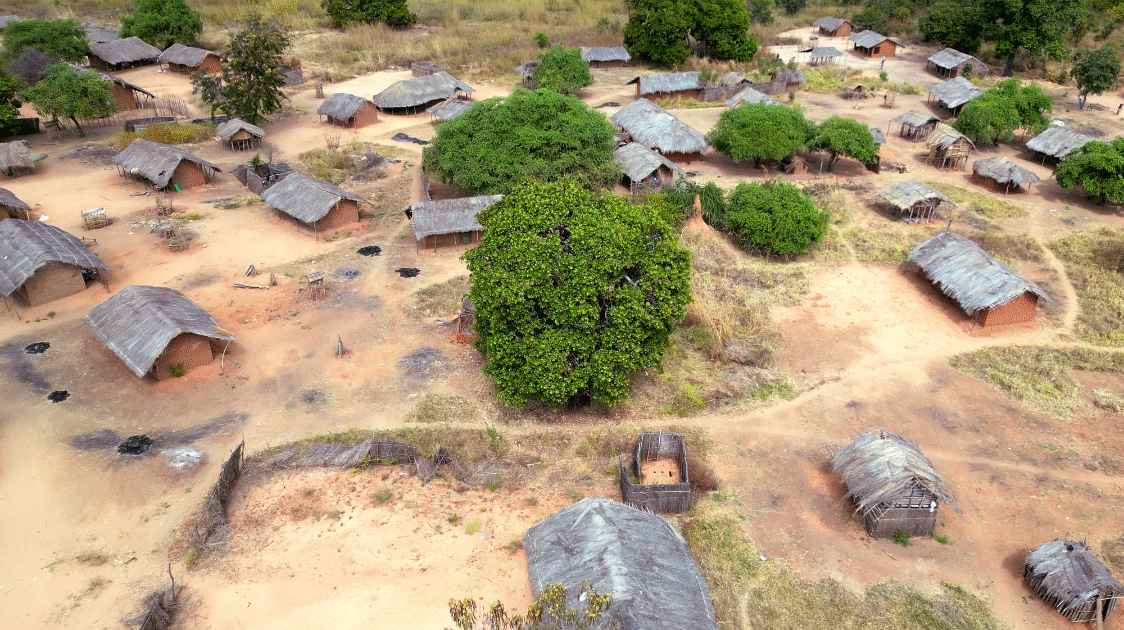

In the context of CBNRM, proprietorship promotes economic justice by empowering marginalized communities to make real choices about their own lives.

As Murphree describes in Masoka Village, Zimbabwe (Jones & Murphree, 2001; Taylor & Murphree, 2007), the psychological or attitudinal component of proprietorship is powerful – ‘this resource is ours’ awakened a sense of nurturing for wild resources that had long lain dormant under a centralized wildlife regime. ‘We see now,’ said one elder, ‘that these buffalo are our cattle’ (Murphree, 1991).

Thus, proprietorship enhances social and collective processes of reciprocity, fairness, and control, beyond the cold individualistic calculus of cost, benefit, and maximization.

We should also not presume that these advantages are linked only to individual private property (Hess & Ostrom, 2007) because, in certain circumstances, collective property has significant advantages.

Individuals gain pride and identity from being members of sports teams, clubs, and even public limited companies. Why would they not also gain pride and identify as members of private-community management regimes in CBNRM?

Property as capital

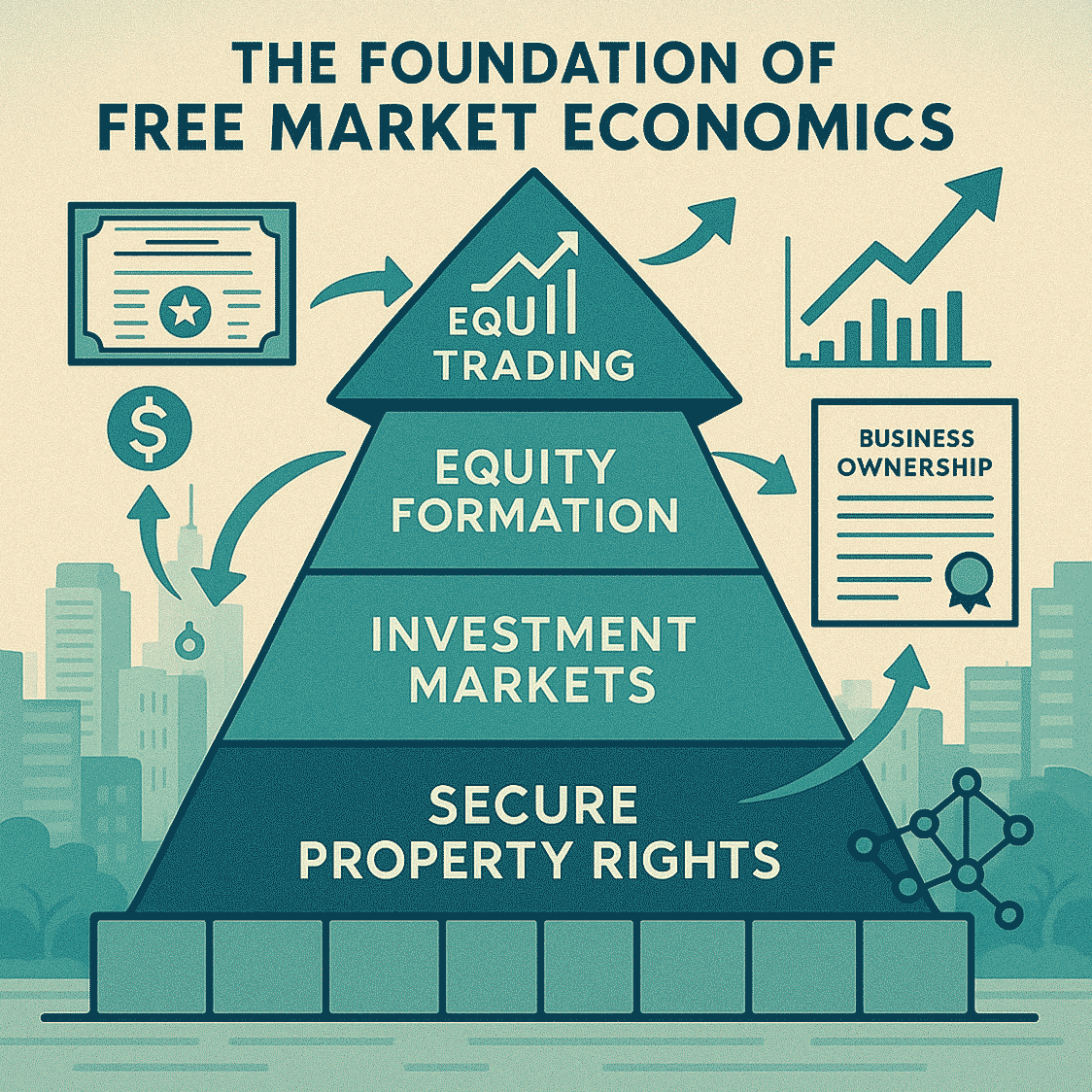

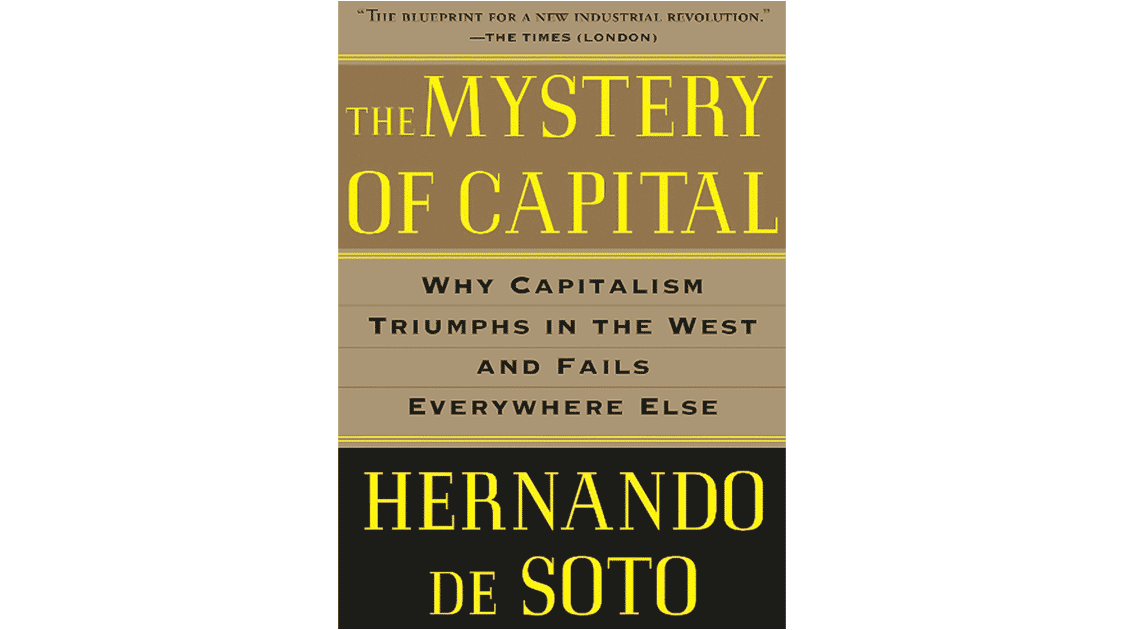

In his thought-provoking book, The Mystery of Capital, Hernando de Soto (2000) suggests that poor people own large amounts of capital, but that this capital is effectively dead because it cannot be put to good use due to the legal haziness surrounding informal property rights.

Formalizing informal property rights, he argues, enables poor people to convert their dormant assets into capital and increase their wealth.

Simply knowing who owns the resource is important because it is difficult to do business where property rights are unclear or contested.

Legal clarity is the foundation for community-private partnerships and the recapitalization of many community wildlife areas in southern Africa (NACSO, 2015).

De Soto also emphasized the importance of property as a form of equity, for instance, in developing wildlife businesses in partnership with the private sector.

However, outright mortgaging of land rights is risky, and CBNRM can be highly effective with non-transferable property rights and title.

In transitional economies, the definition of property rights is further weakened by the ambiguous co-existence of modern and traditional systems.

Thus legislated de jure rights, granted and enforced by governments, overlap and compete with, and have ultimately displaced, de facto local rights (Pomeroy, 1995; Ostrom, 2000; Arnold, 2001) that have evolved over many generations and have considerable local legitimacy even where they are not entrenched in the formal system of laws and legislation.

It is difficult to do business where there is confusion over rights and responsibilities.

Moreover, mechanisms of exclusion and control break down in ill-defined dual systems so that wild resources are overexploited as non-property.

Understanding property

Types of ownership

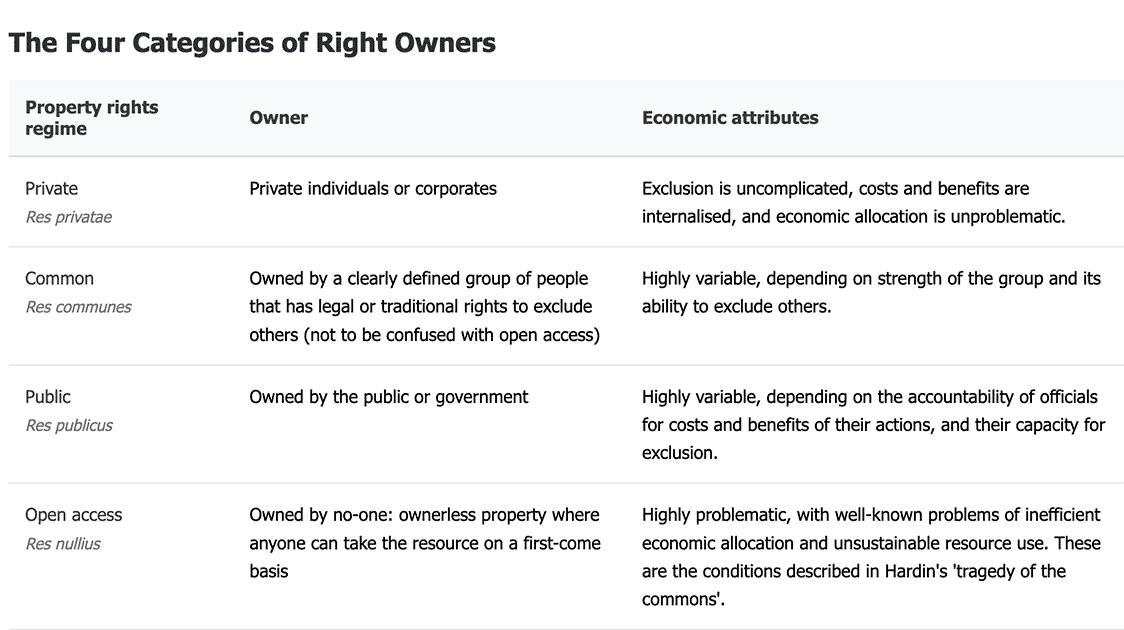

Most people are familiar with the four types of property rights defined in the table below.

• Individual private property (res privatae): Private or freehold property is when an individual, or an individual entity such as a firm, owns the resources.

Theoretically, the owners are fully accountable for the costs and benefits of actions, leading to economically optimal solutions.

• State property (res publicus): Where the rights of ownership and management of land and wild resources are vested in the state.

Where states are publicly accountable for costs and benefits, this can lead to economically sound outcomes; however, this is often not the case.

• Common property (res communes): Common property is often confused with open-access property regimes.

However, common property is characterized by rights that are held and exercised in common by a group with clearly demarcated membership, possessing the legal right and capacity to exclude non-members from using the resource without permission or payment (Ostrom & Hess, 2007).

I avoid the term ‘common property’ because, outside of a small number of academics, it is widely misinterpreted as common to all, rather than common to a small, defined group.

Academics defining common property as rights ‘vested in some form of collective’ (Randall, 1983) or as being held by ‘an identifiable community of interdependent users (Feeny et al., 1990) leave open the scale, character, and function of the collective.

Moreover, until recently, common property was viewed as primitive or archaic, counter-economic, and a relic of less developed times, particularly the period preceding the enclosure of the commons in 18th-century Europe.

• Open access (res nullius) or non-property: These regimes are where rights are not well defined, so that resources are open for anyone to use, resulting in over-exploitation (Hess & Ostrom, 2007). This is unowned property, but it is free to be claimed and belongs to the first taker.

Exclusion

These four categories of property rights are not always helpful in predicting resource outcomes.

A much stronger predictor of outcomes is the concept of exclusion.

Functionally, this suggests two extremes of property: property where there is effective exclusion (by the state, individual, or communities) and non-property where exclusion is ineffective.

Non-property includes weakly implemented state ownership, weakened forms of common or community property, and res nullius and open access property regimes.

Exclusion is a critical concept, implying that anyone wishing to use the resource must negotiate with the owner, who can be a state or a non-state actor.

Well-protected national parks are a good example of exclusion achieved through effective public management.

However, poorly protected parks, where the state claims ownership but lacks the capacity to enforce exclusion, quickly degrade into de facto open-access or non-property.

The decline of wild resources is correlated with weak exclusion.

Public ownership of wildlife may have been crudely adequate in an empty world.

Still, it often degenerates into non-ownership in a full world where the value of resources increases without a concomitant improvement in the capacity for exclusion.

Exclusion is commonly associated with private property applied by individuals, groups, companies, and corporate bodies.

An important, but neglected, form of ownership is ‘private-community property’.

It is a fallacy that wild resources cannot be owned as a community’s private property.

Indeed, the core purpose of CBNRM is to create community-private resource regimes with strong rights and the capacity for exclusion, thereby overcoming the problems of open-access or non-property.

Some academics would argue that the term ‘common property’ implies a distinction between private and community property, but in the real world, the term ‘common property’ is too ambiguous and often confused with non-property, concealing the importance of private community ownership in CBNRM.

I prefer explicit terms like ‘private-community ownership’ and see the goal of CBNRM as incorporating a Village Company.

I use the term ‘Village Company’ to emphasize the need to grant communities legal rights and personality, as well as a structure akin to that of a business and shareholder ownership.

This structure protects the rights of members because they are legal shareholders of the CBNRM business.

It also defines the roles and rights of members and officers, and the procedures to be followed for making decisions (especially about money).

Moreover, it differentiates CBNRM communities from the somewhat nebulous administrative committees of project interventions and the problems commonly associated with them.

Internally, members of a Village Company have legal status as shareholders and can hold their leaders to account through commercial legal mechanisms when local social processes fail—externally, giving communities legal personality as a Village Company provides more protection than administrative or policy arrangements.

(Prof Brian Child is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida and the Life Through Wildlife Project director. His book, “Sustainable Governance of Wildlife and Community-Based Natural Resource Management”, is available on Amazon.)