Simon Says – A Reversal of The Game: Pay Close Attention to What Those Who Wish to Ban Trophy Hunting Say

By Hank's Voice

Hunting season is year-round, with no limits. The online and press version, that is, wherein very vocal, hateful people, brimming with bloodlust, hunt those on hunting safaris in Africa.

These online predators typically hunt in packs, often reaching frenzied levels, in lynch mob, psychologically disturbing proportions, doom scrolling, and lashing out at any legal hunter they can find.

Using a clickbait tactic, they lure ever-increasing haters to their persecutory online pursuits, while donation-seeking scavengers circle greedily, enticed by the possibilities of capitalizing on monetary "meals".

No regulations or restrictions effectively govern their actions. Nor must they prove any proficiency in the subjects they are criticizing or direct investments in the areas and programs they are condemning.

And all the while, they desperately try to convince others that their actions will – SAVE THE ANIMALS!!!

Many of them are simply ignorant, bored, and seeking attention. Many may be well-intentioned but misinformed.

But tragically, some have firsthand experience in Africa that not only should know better, but surely should realize that their intent to eliminate legal hunting will have rippling negative impacts on their own non-hunting uses of wildlife.

This last category features people, primarily in the photo tourism industry, who prey upon gullible minds, easily misled into thinking that taking only photos is non-consumptive and that all of Africa is reminiscent of an artistically filmed nature documentary.

Hakuna matata!

Remember the children's game Simon Says? The one for three or more players, where the leader (Simon) gives commands that everyone else must obey when the action is preceded by "Simon Says"?

Players are eliminated if they don't, or if they perform an action Simon didn't authorize. That's sadly like how these dangerous games of publicly vitriolic condemnations of legal hunting are operating.

Ironically, but fittingly, the one leading these online persecutions is indeed named Simon. The CEO of Africa Geographic – Simon Espley.

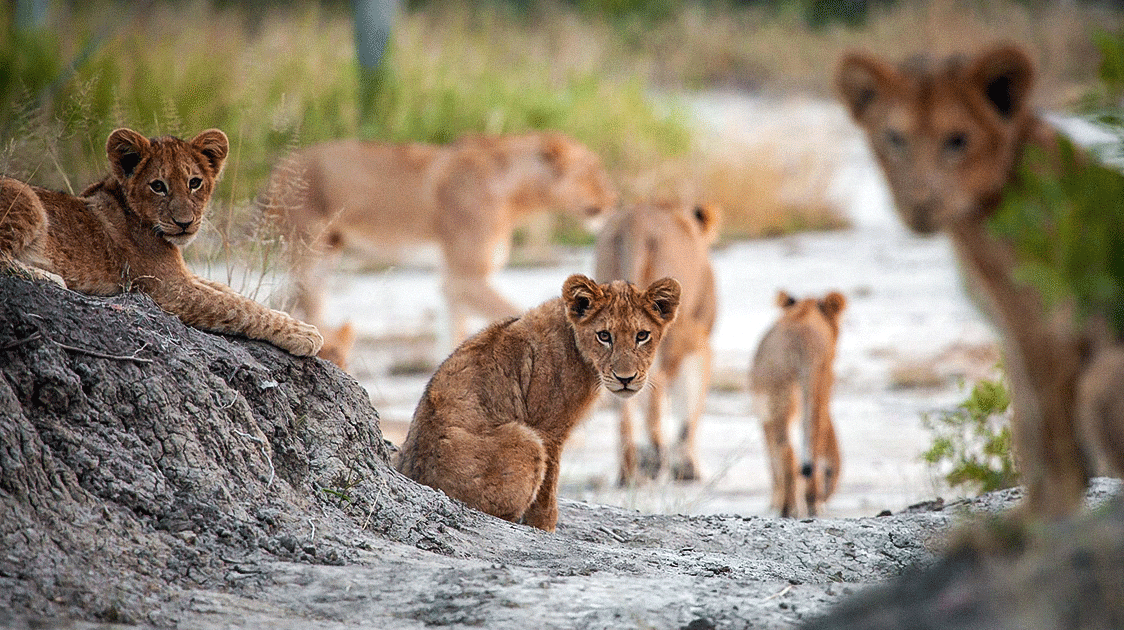

Last year, commands given by him and his cronies pertained to elephants in northern Tanzania. This year, the focus is on lions in Zimbabwe's Hwange region.

Simon Says: GET TROPHY HUNTING STOPPED OR LIONS ARE DOOMED!!! THEY SHOULD ONLY BE PHOTOGRAPHED!!!

But, just as with the elephants, the complexities involved in lion conservation for these endangered species are definitely not that simple.

To quote Yogi Berra: "It's déjà vu all over again."

As before, claims about a lack of transparency from the hunting industry abound.

Yet this time, Africa Geographic not only wouldn't answer legitimate inquiries but also limited commenting and even blocked people who disagreed with their narrative, claiming they did so because they had more important things to do.

Even researchers from Oxford's WildCRU and those at the SATIB Trust declined to respond. All of whom were involved in collaring the lion in question.

Andrew Loveridge, University of Oxford Research Fellow in WildCRU, wrote a book called Lion Hearted: The Life and Death of Cecil & The Future of Africa's Iconic Cats.

Information for this article was gathered from the book, along with the Conservation and Wildlife Fund's annual reports, and various social media posts to gain a more comprehensive perspective.

Similarities (both real and perceived) between the Amboseli elephants and Hwange lions include:

- long-term research projects involving radio-collared animals,

- claims that only photo tourism should earn money from them, but all are expected to bear the costs of supporting them,

- individual animals are well-known publicly, their populations are confined to parks or countries,

- they are the most important animals in their ecosystems,

- trophy hunting is the most concerning cause of death ecologically,

- and genetics are being jeopardized

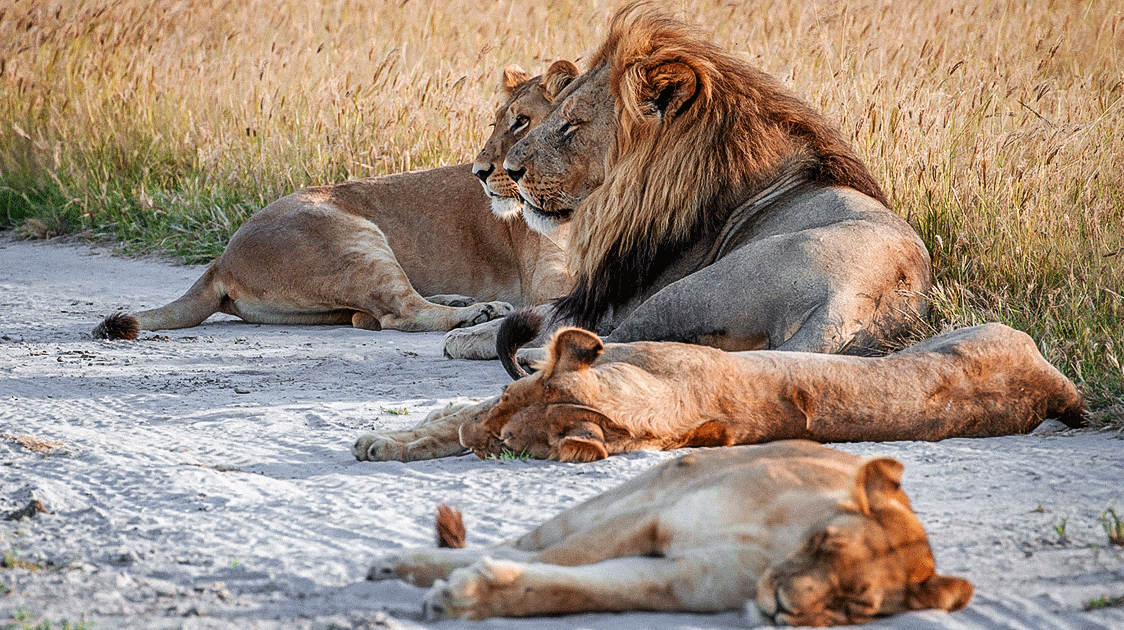

Hwange's lions have been intensely monitored since 1998. By 2018, more than 160 had been collared.

Since only about 5% of Hwange is open savanna, collars are necessary to keep tabs on lions effectively. They should not be viewed as claiming possession of an animal, making them sacrosanct.

That skews data and biases research. Cecil was the 42nd collared animal to be shot since the lion project started, but the first to incite international interest.

Spin-off articles about Blondie claim he was legendary and photographed by many awestruck tourists from all over the world.

If true, they must be greedy and don't like to share, as even by scouring the internet, only a handful of photos and videos are publicly available.

Even Cecil was really only known by researchers and some tour operators before the media scat storm after he was hunted.

It is claimed that Blondie earned a substantial amount of money for photo lodges.

However, he had only been seen occasionally for a period of perhaps two years, and most tourists enjoy seeing any lions, really.

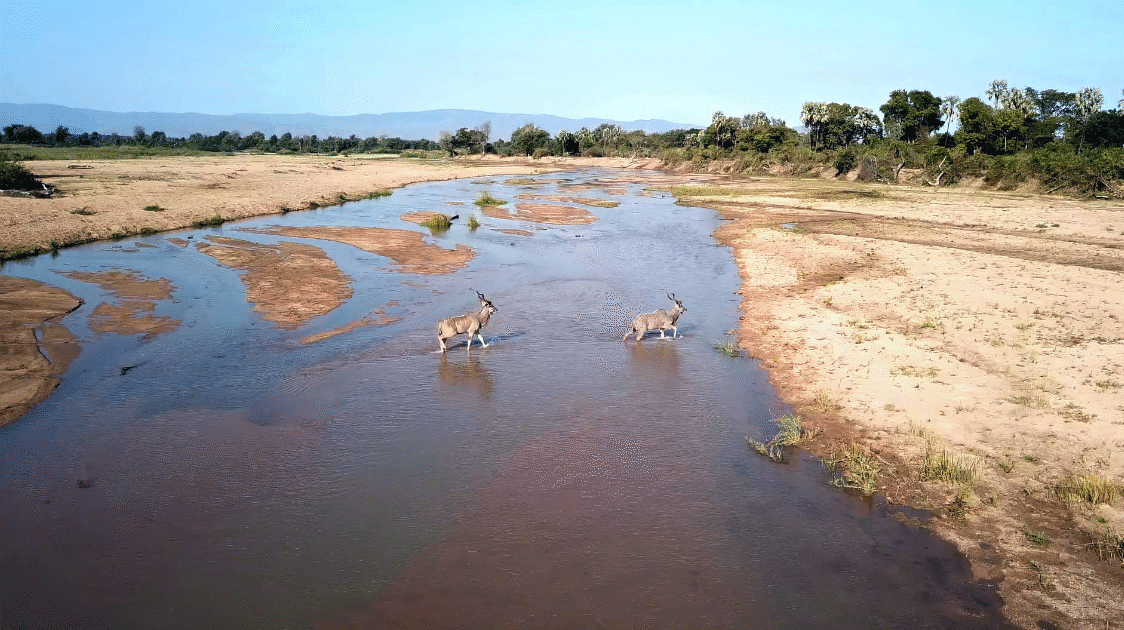

Hwange lions, just like Amboseli elephants, move in and out of the park boundaries regularly as the parks aren't large enough to fulfil all their needs.

Whilst the average lion home range size in Hwange is 500 sq km, some males cover ranges greater than 1000 sq km, traversing 60km in one night.

This inevitably leads them to navigate an array of land ownership and use types, territorial occupancy, and a prey density gradient, with the highest prey density within the park and the lowest in the communal lands.

Home range sizes are based upon prey availability, which is determined in part by the density of waterholes. A high percentage of kills occur within 2km of water sources.

Lions eat a lot, and they are not the only predators living in this region. Packs of over 20 wild dogs, leopards, hyenas, and other predators are also hungry.

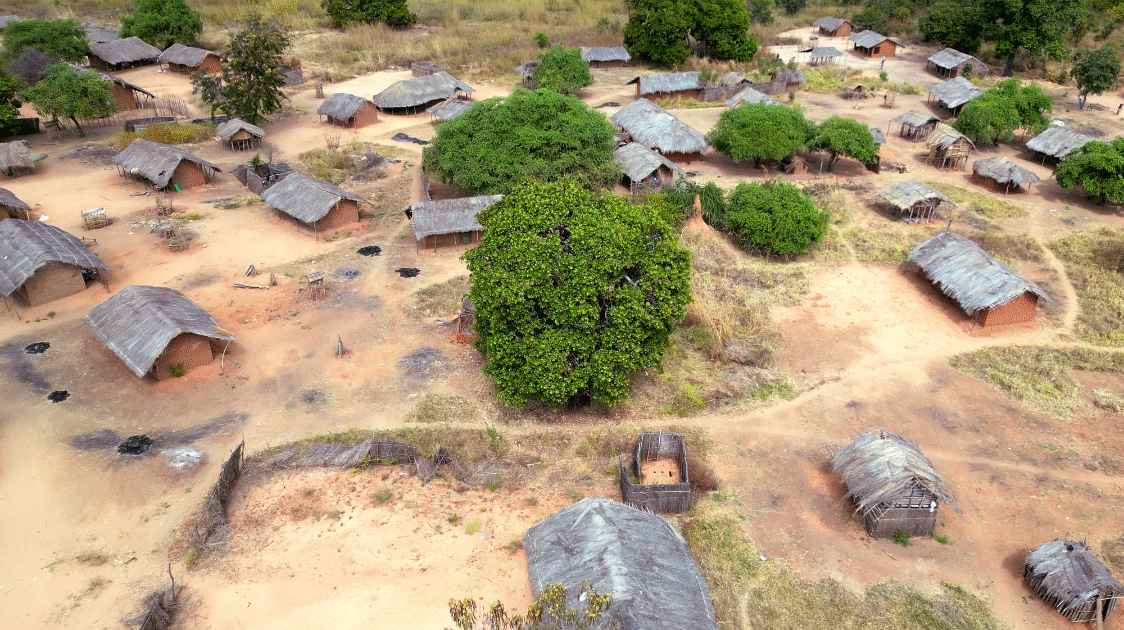

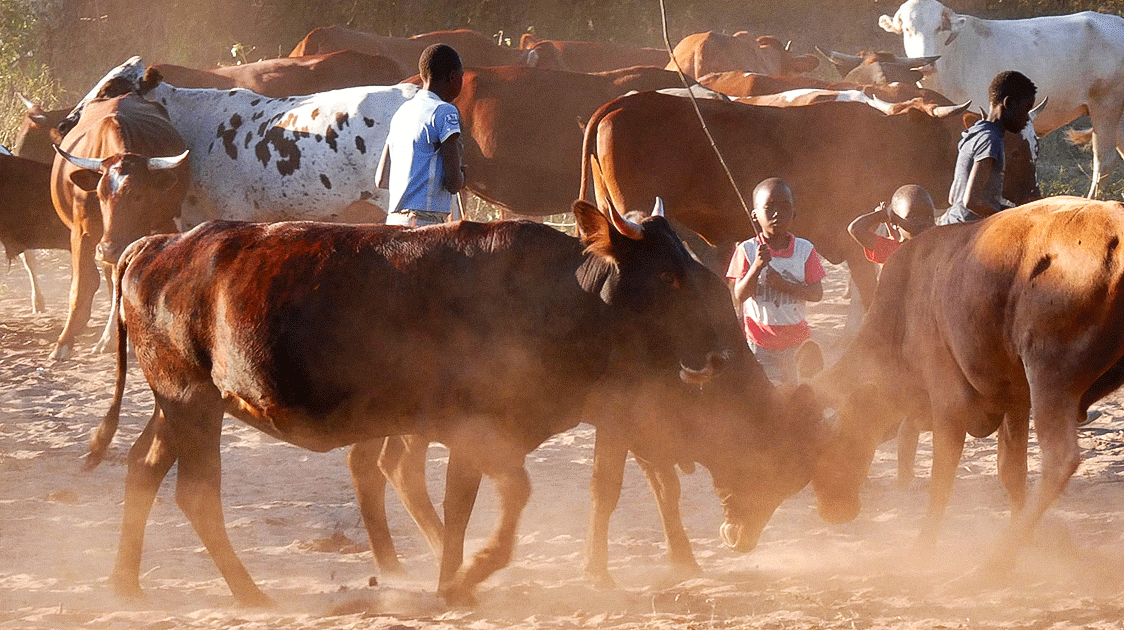

Additionally, prey species are continuously impacted and limited by the increasing numbers of livestock required to support growing human populations.

The habitat that supports prey species has been significantly negatively affected by the rising numbers of elephants. In 2018, when Loveridge's book was published, there were 30,000 elephants in Hwange. Currently, there are 45,000.

Photo tourist exclusivists have a Simon Says command of: LEAVE THESE ANIMALS FOR US TO ENJOY!!! But why should the desires of tourists who only visit for a few days take priority over the concerns of people resident in the area?

Loveridge's book discusses this grave issue in detail.

Whilst tourists view park duties as providing animal sightings and photo opportunities for them, parks acknowledge that part of their role is to protect people and their livelihoods from wild animals; thus, the usual response to livestock raiders is to shoot them.

From 2000 to 2018, Loveridge noted that over 50 lions were known to have been killed for depredation. Some by livestock PAC (Problem Animal Control) teams sent by parks, which is how it's supposed to be handled.

But they are often poorly provisioned, lacking vehicles and ammunition, or are too far away to respond quickly enough.

Inevitably and understandably, irate locals then resort to using brutal gin traps, snares, or poison.

Numbers killed like this are likely significantly underestimated due to the illicit nature of the killings. Still, almost equal numbers of both sexes are affected, with many more adult females and young males killed than mature males and young females.

Lions are also poached within Hwange National Park itself. In one WildCRU study, 77% of lion deaths were caused by people.

Of these, 30% were legally hunted, 19% were snares, 23% were retaliatory killings, and 5% were hit by trains or cars.

Sociological changes and environmental conditions exacerbate the threats to local people's lives and livelihoods posed by lions.

Young Ndebele boys, who would traditionally have been herdsmen, now attend school and hope for good jobs in the city, as there is not enough salaried work for them to remain in remote areas.

This leaves the strenuous agricultural labor to older generations, which is especially stressful during the crop-growing season.

Predation on cattle peaks in this wet season, as waterholes fill up, wild prey disperses, and hunting becomes more difficult for lions.

People also then herd their cows away from the villages, towards park boundaries, so their crops don't get eaten or trampled. However, more lions also live there, and they relish this easier prey source.

A WildCRU study in the early 2000s recorded predation on livestock in the Hwange region, wherein a high proportion of cattle killed by lions or hyenas wore bells.

Researchers, upon noting this, capitalized on this dinner bell concept and actually called livestock killers in by ringing bells. In the Tsholotsho Community Area east of the park, over 700 predator attacks were recorded in a 5-year period.

It's therefore easy to understand why communities are often hostile to parks, as dispersers and travelers from these core populations can be problematic for them.

Local attitudes typically reflect a desire for parks to keep lions in check. They suggest fencing the park.

However, the cost is prohibitive, as it would also need to be elephant-proofed. Once fences are erected, intensive management is necessary within.

Fencing (and abandoned telephone lines) also gets stolen to make snares. A prime example is the 285km of galvanized steel wire stolen from the Foot and Mouth Fence in the Hwange area—an amount that has the potential to produce 71,000 snares.

The majority of lions are also within the core population, centred in the park. As a highly territorial species, dispersal is essential.

As usual, much ado is made of breeding age, genetics, and infanticide.

But was one of Hwange's most prominent pride holders actually a result of trophy hunting impacting the population?

"Mpofu" was reproductively dominant for just over 9 years, an unusually long tenure for a pride male. He sired over 50 cubs in 6 different prides, with 20 of them reaching adulthood.

During that era, trophy hunting quotas were significantly higher than they are currently, and included females, resulting in fewer large males and subadults, which seriously reduced territorial competition.

A similar paucity of breeding-age rivals also occurs in the Amboseli elephants, due to deaths from drought, poaching, and human-wildlife conflict (HWC).

In the early 2000s, lion hunting was suspended in the Hwange area due to concerns about declining lion populations.

During this period, male survival increased to greater than 80%. More coalitions formed, and smaller territories developed.

In the core study site, which spans 3,000 sq km, there were seven territories, whereas previously there had been only two.

However, male lions typically leave their maternal territories by about 3 to 4 years of age.

More territories mean more potential conflicts with their holders during dispersal, more potential takeovers, and a greater number of prey animals required.

Infanticide, although a natural part of lion biology, is not inevitable. Nine cubs of Cecil's last litter were spared when his pride was taken over after he was killed.

Cecil himself had both killed cubs and had his cubs killed at various times during his lifespan. Male lions are described by Loveridge as "murderers turned into family men".

Lionesses are not entirely helpless when it comes to protecting their cubs. But, considering the problems dispersing lions face, particularly in the communal lands, it's possibly a good thing that more cubs don't survive to that stage?

Africa Geographic enlisted another Simon Says commander in the Hwange lions game—Beks Ndlovu, cofounder of the Conservation and Wildlife Fund, dedicated to the Hwange Landscape Conservation Initiative.

In 2015, in reaction to Cecil's death, he proclaimed: "In my personal capacity….I strongly object and vehemently disagree with the legalization and practice of hunting lions in any given area. I will personally be encouraging Zimbabwe National Parks and engaging with the Government Officials to stop the killing of lions with immediate effect."

It didn't happen then, nor has it happened ten years later.

His own organization even claims to collaborate with the Zimbabwe Professional Guides Association (ZPGA) in conservation efforts, as noted in its 2022 annual report.

And, quite notably, lists serious problems faced. Snares (3,474 removed from 2017-2023), cyanide stations for poisoning wildlife, timber poaching (one use of which is to create souvenir carvings for tourists), and bushmeat poaching.

These are only a few of the "rest of the story" important considerations that anti-hunting advocates conveniently overlook in their crusades.

Simon Says, both the game and the real-life analogy forms of it, are run by dictators from whom no questioning by the players is allowed.

They simply must obey what Simon says.

The goal of the game is to eliminate as many players as quickly as possible, thus allowing for no variation, diversity, assumption of different roles, or contributions in ways that they can.

It's simply my way or the highway.

Is that what we want? Is that what conservation needs? Hunting doesn't feel that way. Communities don't feel that way. However, many in the photo tourism sector and on social media appear to do so.

Simon Says, people should only photograph lions. But hunters want to hunt them. And communities want protection from them and compensation for their losses.

Mixed land uses and increasing human populations will require more animals to be killed. Simon Says, hunting's a relic activity that should be relegated to the past, but reality dictates that it will become increasingly more essential in the future.

In a February 27, 2024, op-ed piece, Simon Espley stated that, "Blaming others will not win any battles against the many threats faced by the wildlife industries - habitat loss, poaching, human-wildlife conflict, and climate change, to name a few."

Yet his Simon Says commands urge persecution and elimination of trophy hunting.

In his book, Loveridge says: "Safeguarding the last wilderness strongholds of the species, and preserving the fragile habitat links that join them, is the most critical action conservationists can take to halt declines in lion populations."

Former USFWS Director Dan Ashe adds, "Banning lion trophy hunting will not halt the decline of Africa's lion populations. Loss of habitat and conflicts with livestock owners are the most important causes of lion population declines. The threat of habitat loss may actually be exacerbated if hunting areas are no longer protected."

Africa is struggling to fund what habitat remains and cannot afford more habitat loss. Trophy hunting helps protect the majority of wildlife habitats in many countries.

Mostly on lands that are not suitable for photo tourism.

Remove hunting as a conservation tool, and human settlements, livestock, and agriculture will readily consume those vacant lands.

The purpose of the original Simon Says game was to develop listening skills and distinguish between genuine and fake commands.

Anyone questioning Simon or not obeying gets eliminated.

However, this is not a practical approach to conservation strategies.

Nature's future, in Africa or anywhere else, requires diverse approaches to addressing the challenges it faces.

Simon Says-style dictatorship might be fun child's play, but it is a game currently being played in the conservation community that will lead to catastrophic declines in game animals.