Mutualism and Murder: The Evolutionary Logic of Honeyguides and Why it Matters

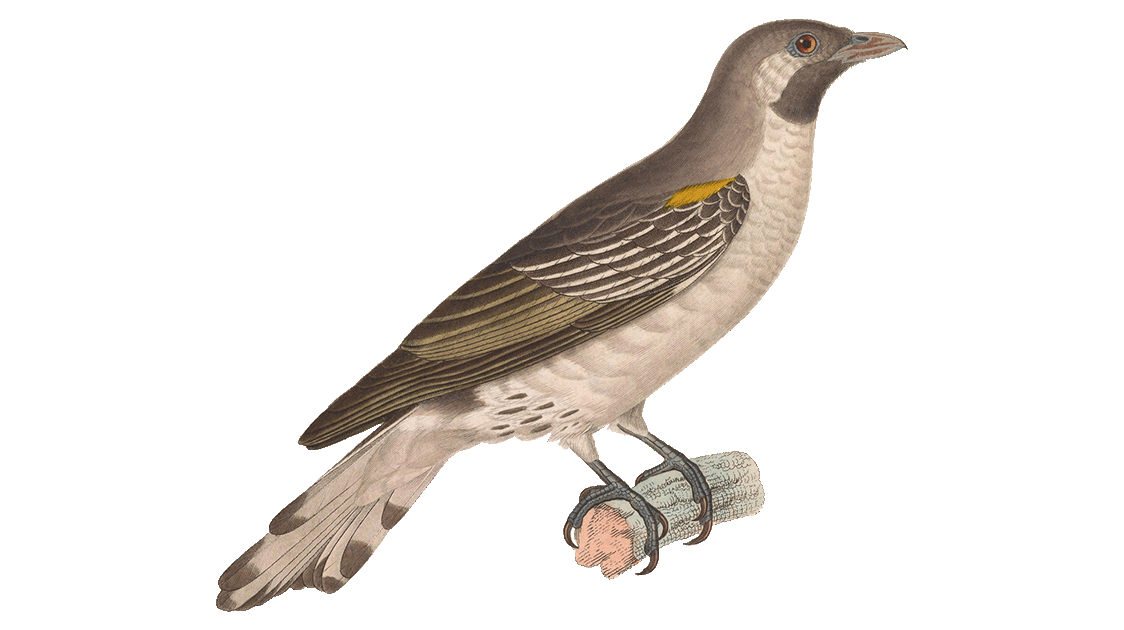

The honeyguide family, Indicatoridae, contains 17 species across four genera, distributed through sub-Saharan Africa and into parts of Asia.

All are obligate brood parasites.

Most eat beeswax.

But the behavior that gives the family its common name, guiding humans to bee colonies, is only documented in one species: the greater honeyguide (Indicator indicator).

Some older literature claims the scaly-throated honeyguide (Indicator variegatus) also guides, though this is disputed.

The remaining 15 species are named by taxonomic association only.

The greater honeyguide presents one of the more unusual behavioral profiles in African ornithology. The same species that maintains a documented symbiotic relationship with human honey gatherers also reproduces exclusively through brood parasitism (laying eggs in the nests of other birds and leaving host species to raise its young).

Reproductive Strategy

Female honeyguides target cavity-nesting species, including bee-eaters, hoopoes, kingfishers, and scimitar bills.

The newly hatched chick, still blind and featherless, possesses temporary bill hooks that it uses to kill host chicks and destroy remaining eggs.

This ensures the honeyguide monopolizes parental care from the foster parents.

Research published in Biology Letters documented this behavior for the first time using infrared cameras in underground nest chambers, confirming that one to five minutes of active biting sufficed to kill host young.

The hooks are retained for at least 14 days, which is sufficient to address late-hatching host chicks in asynchronous clutches, and they gradually grow into the developing bill rather than being shed.

By the time the honeyguide fledges at around 30 days, there's no visible trace of the weaponry it used as a hatchling.

What makes this system particularly interesting from an evolutionary standpoint is the source of the selective pressure.

In many brood-parasite systems, cuckoos being the textbook example, hosts evolve egg-recognition and rejection behaviors, driving parasites toward increasingly sophisticated mimicry.

The honeyguide's primary hosts, particularly the little bee-eater, show no such discrimination. Experimental research found that bee-eaters accepted eggs even much larger than their own.

Instead, the evolutionary pressure comes from conspecific competition. When a female honeyguide finds a nest already containing another honeyguide's egg, she punctures it before depositing her own.

Research has documented superparasitism in 35% of parasitized nests in one Zambian study population.

The honeyguide's egg characteristics appear shaped more by interference competition among honeyguides than by host rejection.

The Human Partnership

Honeyguides lead human hunters to wild bee colonies, then feed on wax and larvae after the nest is opened. This represents one of the few confirmed mutualistic relationships between humans and a wild, undomesticated animal.

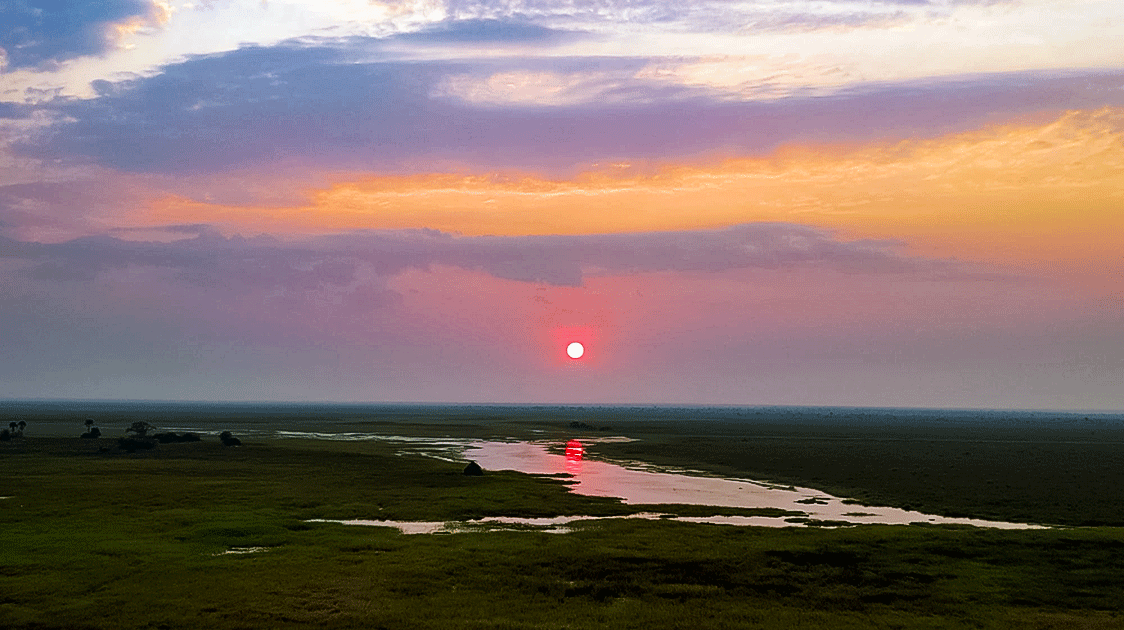

Following a greater honeyguide in the African bush can be an interesting experience

The communication system shows cultural specificity on both sides.

Yao honey gatherers in Mozambique use a distinctive "brrr-hm" trill and grunt.

Hadza hunters in Tanzania use a different whistle.

Research published in Science in December 2023 demonstrated that honeyguides respond preferentially to local signals.

Tanzanian birds were over three times more likely to cooperate when hearing the Hadza call versus the Yao call, and Mozambican birds were almost twice as likely to respond to the local Yao call versus foreign Hadza whistles.

This variation operates at a more granular, localized level than previously appreciated.

A 2026 study in People and Nature recorded calls from 131 honey gatherers across 13 villages in Niassa and found that even neighboring communities use distinct "dialects", with call similarity decreasing with increasing distance between villages, much like human linguistic variation.

Environmental factors such as habitat acoustics didn't explain these differences.

Honey gatherers who moved villages appeared to adopt the calls used in their new community. Both recruitment calls (used to attract a honeyguide over long distances) and coordination calls (used while following a guiding bird) showed this regional patterning.

This suggests learned behavior rather than an innate response, with birds adapting to regional human communication patterns and humans, in turn, conforming to local traditions.

The calls are culturally transmitted, passed between generations of hunters.

What Is Not Known

The popular account of honeyguides leading honey badgers to bee nests lacks solid documentation.

A 2023 study in the Journal of Zoology conducted nearly 400 interviews with honey gatherers across 11 African communities.

Most respondents were doubtful that honeyguides and honey badgers work together, and 80% had never seen the two species interact.

The exception was Tanzania, where 61% of Hadza hunters reported witnessing interactions, but, as the researchers noted, establishing whether the honeyguide actively guides the badger or simply remains near it remains methodologically difficult.

A 1990 paper by Dean, Siegfried and Macdonald explicitly called the relationship a "fallacy," noting that in over 200 years of naturalist activity in Africa, no biologist had observed a honeyguide leading a honey badger to a beehive.

The antiquity of the human-honeyguide relationship is also speculative.

Some researchers have proposed origins dating back 1.5 to 1.9 million years to Homo erectus, coinciding with the earliest evidence of controlled fire, but this remains a hypothesis.

Current evidence confirms the relationship is ancient, possibly hundreds of thousands of years old, but precise dating is impossible given the absence of archaeological evidence for the soft tissue and behavioral elements involved.

Conservation Relevance

The African Honeyguides Research Project is currently tracking these dynamics across southeastern Africa.

There's also a growing body of work examining how honey gathering shapes the ecosystems where it occurs.

Critics have accused honey gatherers of destructive practices, felling trees, starting wildfires, and providing cover for poaching.

But recent research from the Niassa Special Reserve complicates this picture.

Work by Rion Cuthill, Claire Spottiswoode, Sally Archibald, David Lloyd-Jones and a team of honey gatherer collaborators found that while honey gathering does sometimes ignite wildfires, these fires tend to occur during seasons when prescribed burning would be recommended anyway.

Tree harvesting affects only a small proportion of the total population, and recovery rates make the practice sustainable.

The research challenges the "fortress conservation" model, which assumes that protected areas can function only by excluding people, and suggests that, in places such as Niassa, honey gatherers might serve as conservation allies rather than threats, given their intimate knowledge of the landscape and their capacity to detect illegal activity.

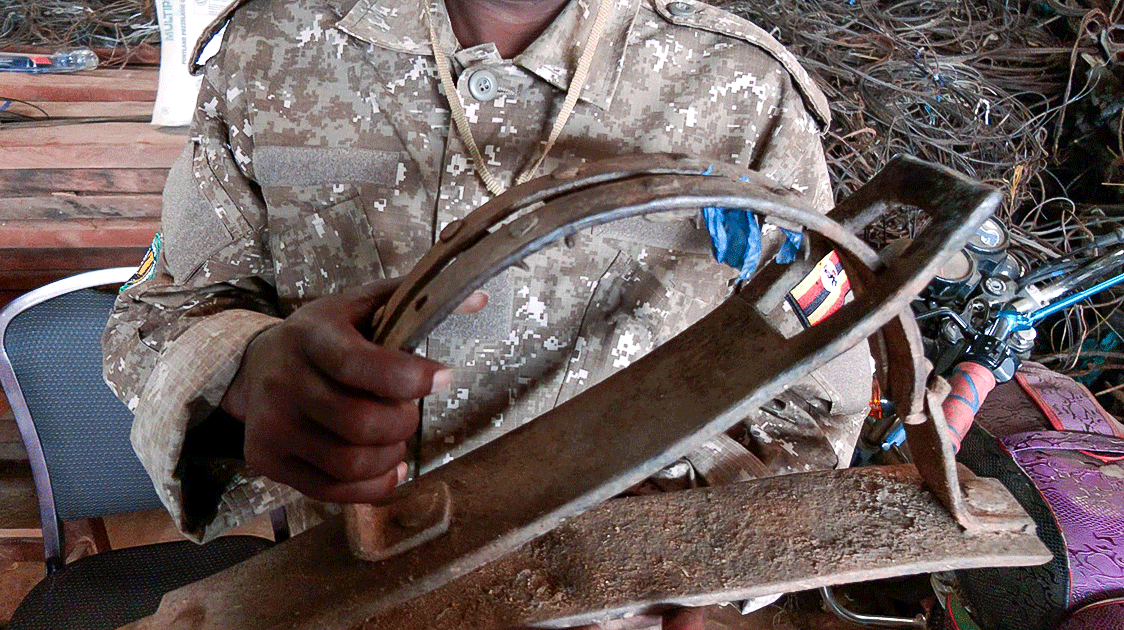

Derek Littleton from LUWIRE in the Niassa Special Reserve, Northern Mozambique, talks about incorporating artisanal beekeepers into the reserve's security system.

Beyond a Novelty

The honeyguide system matters beyond its novelty. As traditional honey gathering practices decline across Africa, so does the mutualistic relationship.

Young people in many communities no longer learn the traditional calls.

Whether honeyguide populations will maintain guiding behavior without regular reinforcement from human partners is an open question with implications for understanding how cultural knowledge, both human and avian, persists or disappears.