Mayo Oldiri, Anti-poaching Operations in Cameroon

By Raquel Reguera

The safari hunting industry is changing. I recently had dinner with an old friend, a big outfitter today, and we joked about it. When we both started (almost at the same time, more than 25 years ago), we mostly showed photos of the big trophies taken; now, we mainly show pictures of live animals. In these times, hunters must validate their passion.

We have carried out anti-poaching from the beginning and continue to do so, but now people want to know about it, and the outfitters must show what they do. Any respectable outfitter should become involved in conservation and anti-poaching forums.

Participating in these groups is an opportunity to exchange different approaches and share experiences while raising awareness amongst participants.

These platforms show the uninformed people that hunters are part of the solution, not the problem.

With the money raised through trophy fees, the hunting companies, especially the African ones, can afford to run anti-poaching units: to have permanent patrols 24/7.

Mayo Oldiri runs four hunting concessions in the savannah regions of Northern Cameroon, two of which border the Boubandjida National Park.

The biggest threats to wildlife in the region include the following:

- Illegal logging and crop farming which has a seriously detrimental effect on vegetation.

- Encroachment of cattle herders. Their livestock not only compete with wildlife for forage, but they also see lions as a threat and kill them wherever possible.

- Gold prospectors set up settlements in the concession areas and national parks and not only cause ecological damage with their mining activities but also actively poach.

- Fishermen often poison the water to catch fish. The local clerics and doctors are trying to educate the villagers about the dangerous consequences of this practice, including the secondary poisoning of scavengers feeding on poisoned animals and the threat to humans of eating poisoned fish and meat.

- Commercial poaching by these groups of people to supply the local and regional demand for bushmeat is a severe problem.

Tackling these problems can only be carried out effectively if there is close teamwork and collaboration between the different safari operators and local wildlife authorities.

Two main strategies have been developed over the years, awareness and incentives (particularly health and education) and strict law enforcement.

To create awareness of the importance of sustainable-use hunting, Mayo Oldiri managers visit villages around the National Park and hunting areas and meet the village chiefs, tribal leaders and police forces.

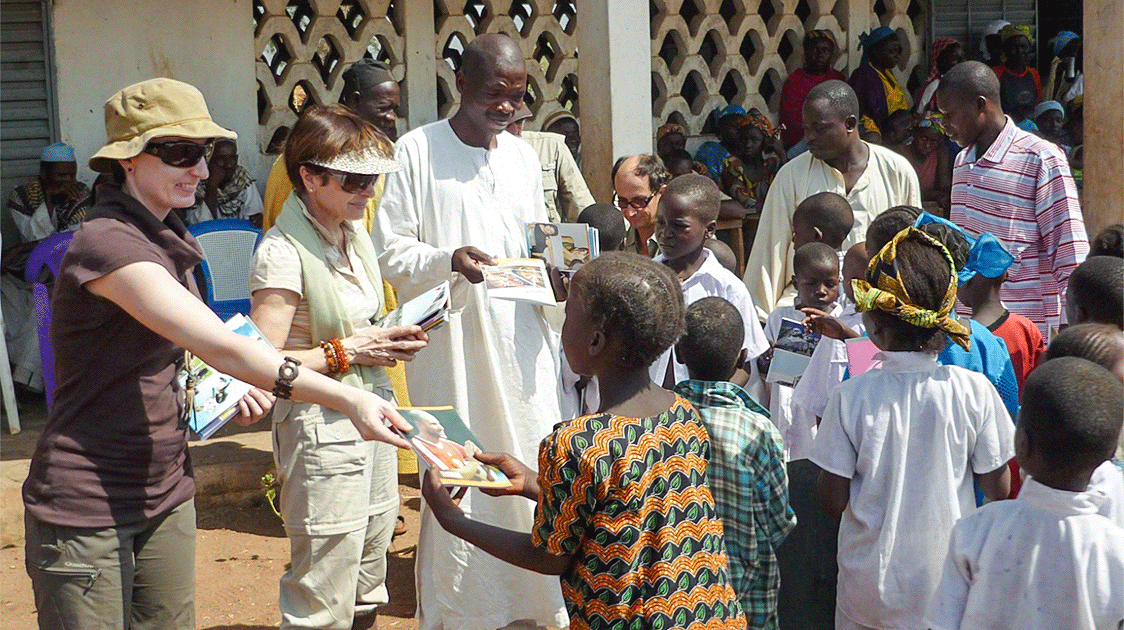

They inform the villagers about the damages caused by poachers and ask for their collaboration in anti-poaching efforts. The local anti-poaching team members give presentations at the schools in the local languages about wildlife to increase awareness and the threats of wire snares and traps.

Education is essential, and Mayo Oldiri regularly provides educational material to the local schools. Many local people are unfamiliar with the wildlife living near them.

Presentations are given in schools about the different species, behaviors and the habitat and materials such as calendars are distributed with clear information about each species to foster appreciation.

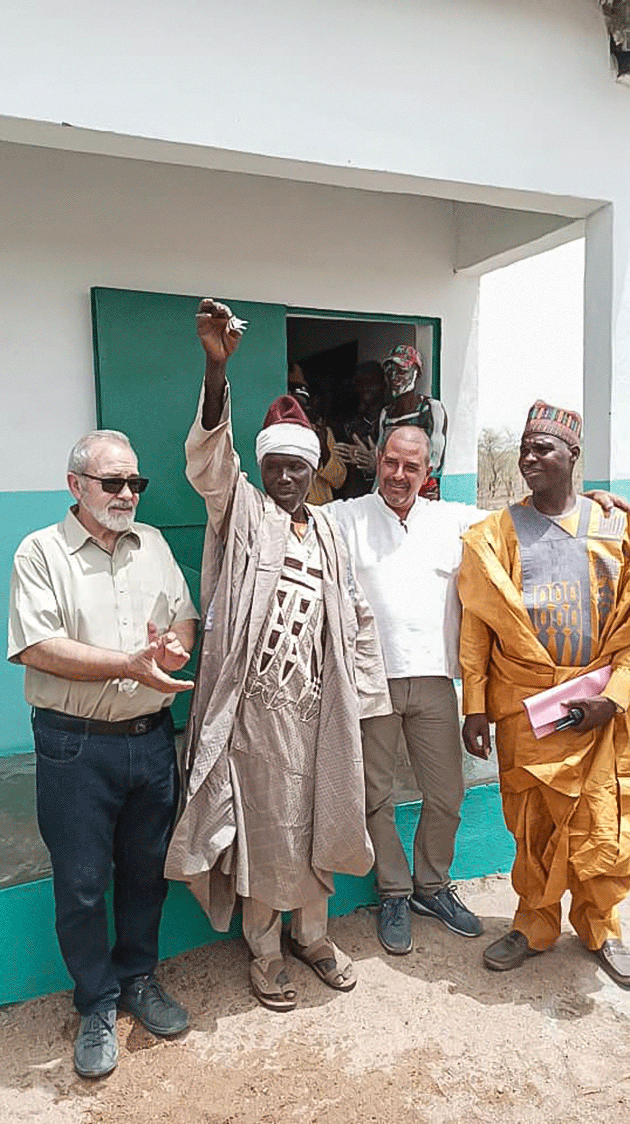

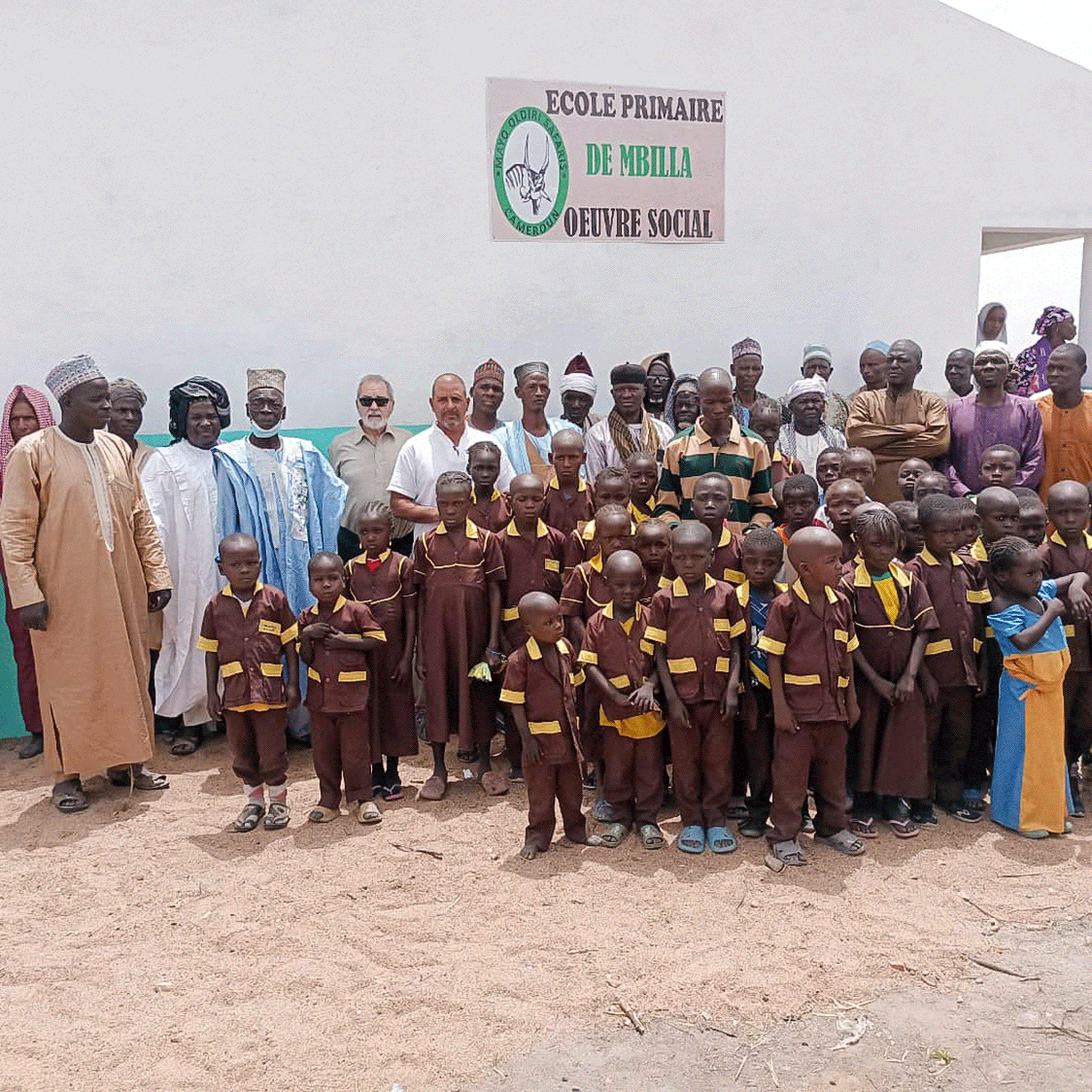

In the village of Mbila, at the entrance of one of our hunting areas, we built a new school building, and Antonio Reguera was there for the inauguration on April 1, 2023.

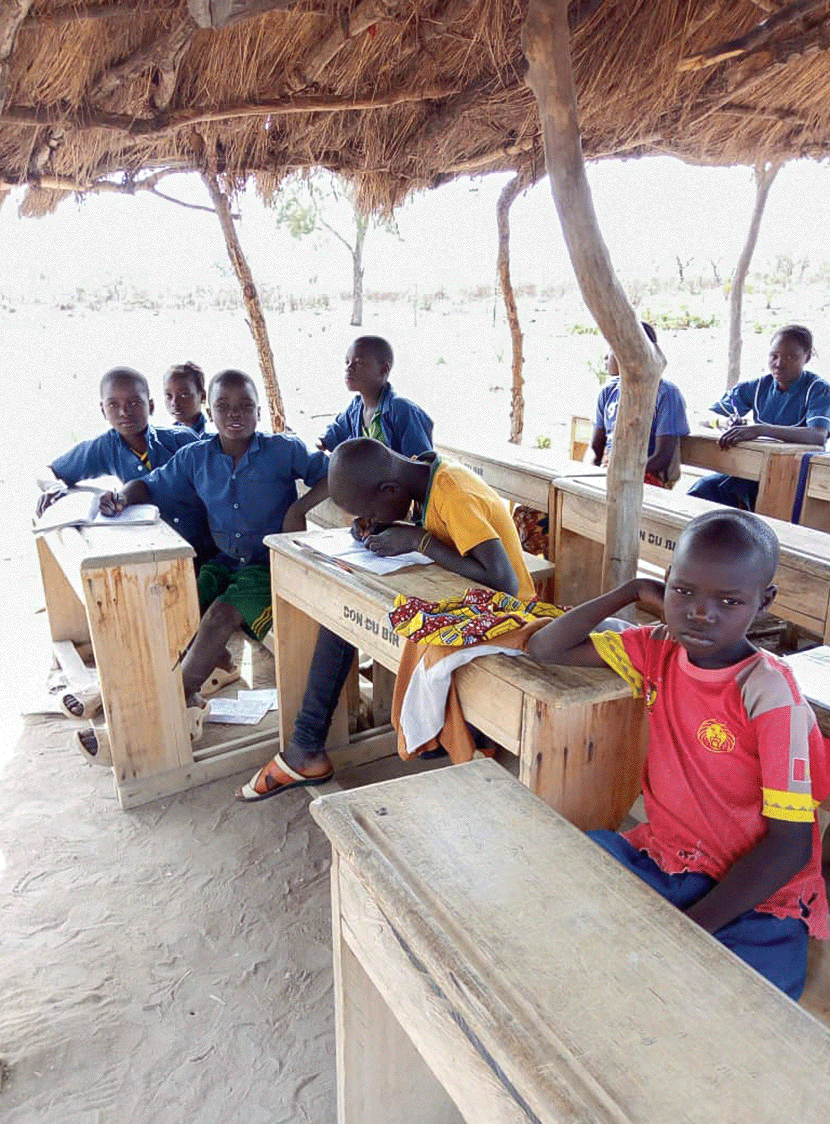

Lessons are now taken inside a modern building instead of a dilapidated thatched structure.

In 2007, the Foundation Mayo Rey (Fundación Mayo Rey, www.fundacionmayorey.org) was created with the assistance of Dr Emilio Sastre, a Spanish doctor friend of ours.

He frequently visited the Rey Bouba region during his holidays and provided free treatment for the area's people with the few medicines he could bring in his luggage.

With the help of the Spanish Embassy and the Lamido, the Foundation built a hospital to allow the population of the Mayo Rey region, of which the capital is Rey Bouba, primary access to health care.

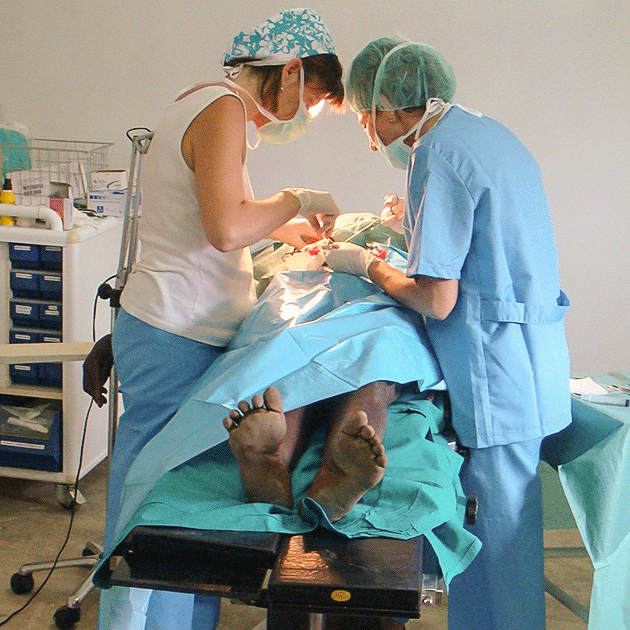

Mayo Oldiri collaborated from the start, helping transport beds, materials and equipment. The hospital opened in February 2010 and specializes in general surgery, pediatric, gynaecology, ophthalmology, deontology, and traumatology.

The hospital is open for several months during the dry season but closed during the rainy season as access is extremely difficult. The medical doctors work for free, and all the materials and equipment are donated from Spanish hospitals or bought with funds from individual donations.

We have established a good relationship with the communities near our hunting areas by providing much-needed employment (we often hire former poachers to work in our anti-poaching teams), medicine, school materials and the meat from the hunted animals for free.

This helps them realize that legal safari hunting brings far more benefits than poaching and that we can be friends and collaborators, not enemies trying to steal their wildlife.

This collaboration works to alert us when foreign poachers appear in the area.

Many visiting hunting clients get personally involved with community projects helping with donations.

The less palatable but vital part of conservation is strict law enforcement.

The poaching activity is not subsistence but a coordinated group of commercial poachers pulling out tons of meat and selling it.

The Mayo Oldiri anti-poaching team enjoys a close cooperation with His Majesty Abdoulaye Aboubakary, Lamido of Rey Bouba and the Director of Boubandjida National, Mr Patrick Tadjo.

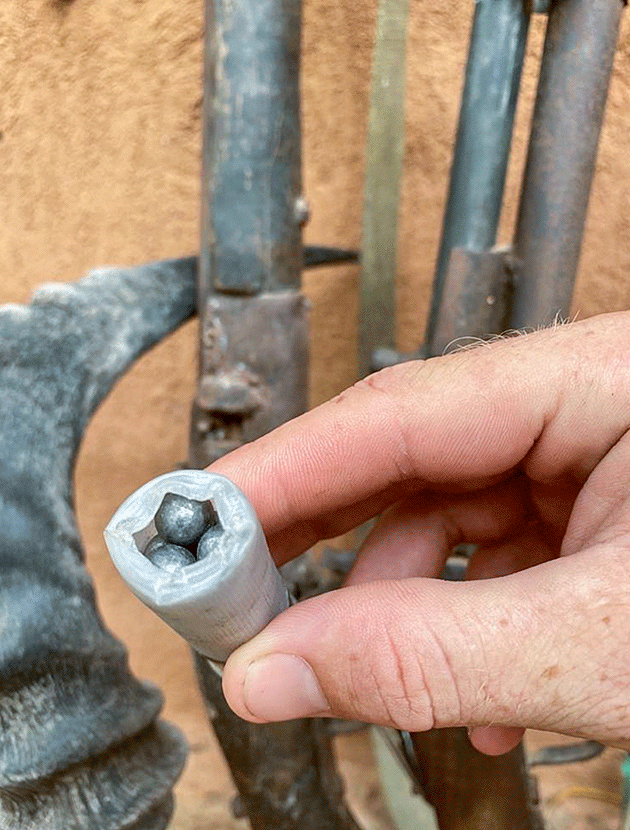

The anti-poaching work involves removing snares and traps, destroying poacher camps and arresting and handing poachers to law enforcement agencies. Depending on the situation, we can enlist help from military special forces.

The teams are well equipped and proficient in fighting the local commercial meat poachers but foreign poaching gangs infiltrating Cameroon from Chad, CAR, Sudan, and Nigeria are a different story.

Animals and poachers don't respect borders, so the cooperation between National Parks, local authorities and hunting companies created a team to fight this poaching scourge.

Even today, sport hunters will see gorillas at least five times during a two-week hunt in the forest. I sometimes wonder if this will be the same in 20 years.

We sadly catch poachers with gorilla parts occasionally; we must stop the killing in this daily war.

Without a shadow of a doubt, we can state that there are more animals in our hunting areas than in many of the National Parks. We fight hard against poachers, and sport hunters provide the finances to do it.

I had the opportunity to travel to Angola the year after the end of the long civil war. Everything was devastated; the mines had pushed the animals to the beach. I will never forget the gazelles running free along the coast and enjoying the waves.

I often contemplate that nature somehow manages to survive, but being able to contribute and partake in the cause makes me feel like I am part of something bigger than myself and part of the solution.

It may sound contradictory to the uninformed, but legal safari hunters are the most proactive group in protecting wildlife.

Non-hunting conservation organizations need to be very careful in spreading misleading propaganda about hunting operators or comparing hunters with poachers.

Actual conservation hunting is not part of the problem – it is part of the solution! Without the permanent presence of safari hunting operations in these wilderness areas, there would be no meaningful control of wildlife poaching.

Sustainable hunting is all about combining biological, economic and also socio-cultural benefits for people and wildlife.