Global Biodiversity Loss, Ecosystem Collapse and National Security

By Dr Daniel Stiles

On 20 January 2026, the UK government released a report entitled Global biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse and national security. While aimed at raising awareness about threats to UK national security posed by biodiversity loss and cascading ecosystem impacts, the report is relevant to all nations.

The report states that this assessment was developed by analysts and experts across the UK Government, but The Times reports that “it was put together with the help of the Joint Intelligence Committee, which oversees MI5 and MI6.”

A longer version of this report was originally scheduled for release last October, but the Starmer government deemed it too alarming and ordered that it be toned down, resulting in a delay.

An “abridged version” has been published following a freedom of information request.

The report nevertheless shows how environmental degradation can disrupt food, water, and health supply chains and trigger wider geopolitical instability.

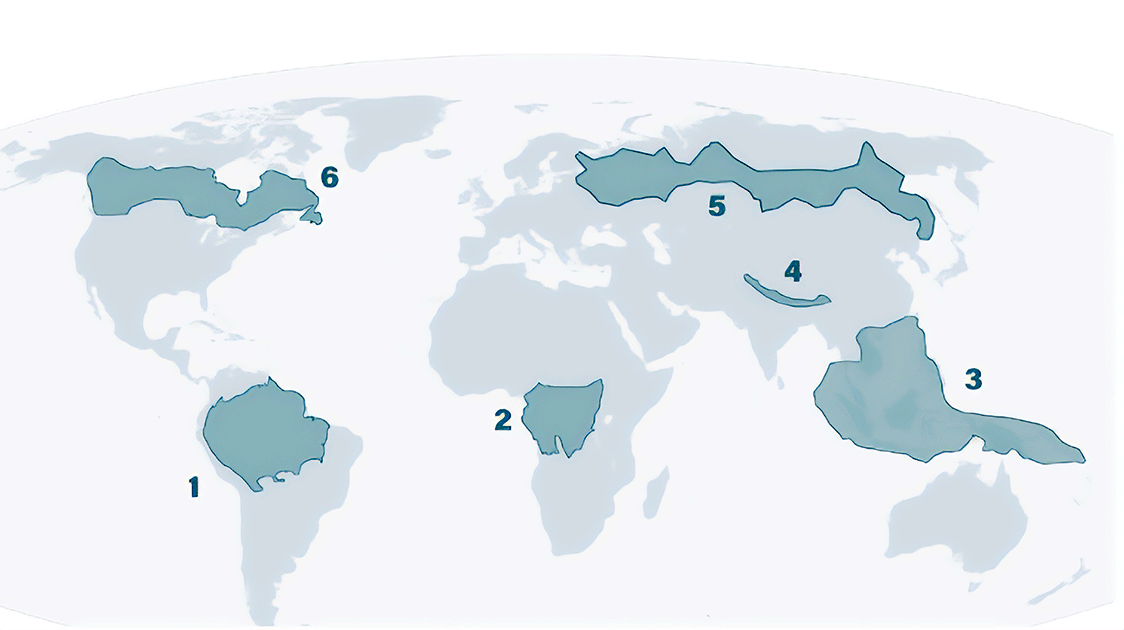

It identifies six ecosystems of strategic importance for the UK and explores how their decline could drive cascading global impacts:

1. Amazon rainforest

2. Congo Basin

3. South East Asia coral reefs and mangroves

4. Himalayas

5. Boreal forests of Russia

6. Boreal forests of Canada

The assessment concludes that excessive biodiversity loss will lead to the collapse of the functioning of these ecosystems, which will lead to:

Migration: rising as development gains begin to reverse, and more people are pushed into poverty and food and water insecurity. A one percentage increase in food insecurity in a population compels 1.9 percent more people to migrate.

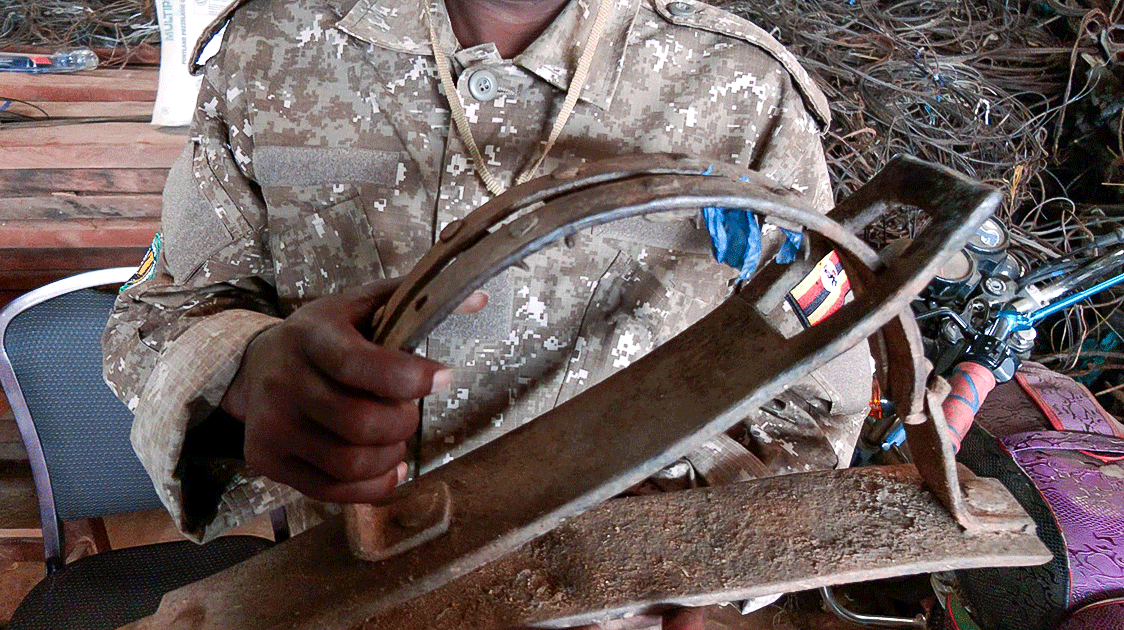

Serious and Organized Crime (SOC): looking to exploit and gain control over scarce resources.

More people pushed into poverty will mean more opportunities for SOC to exploit (e.g., wildlife and people trafficking and black markets in scarce food, pharmaceuticals, and critical minerals).

Non-state actors: including terrorist groups having more opportunities resulting from political instability - e.g., acting as mercenaries or pseudo-governments. They may gain control over scarce resources.

State-level threats: becoming more severe as some states become more exposed than others to risks of food and water insecurity.

Pandemic risk: increasing as biodiversity degrades, people move between countries, and the transfer of novel diseases between species becomes more likely.

Economic insecurity: becoming more likely. Nature is a finite asset that underpins the global economy.

It would take resources of 1.6 Earths to sustain the world’s current levels of consumption. The total annual value of ecosystem services to the UK was £87 billion in 2022 (3% of GDP).

Geopolitical competition: increasing as countries compete for scarce resources, including arable land, productive waters, safe transit routes, and critical minerals.

Political polarization: instability is growing in food and water-insecure areas, and as populations become more vulnerable to natural disasters. Disinformation will increase.

Conflict and military escalation: becoming more likely, both within and between states, as groups compete for arable land and food and water resources.

Existing conflicts will be exacerbated.

As an example of the last one, the original report stated that the decline of Himalayan rivers will “almost certainly escalate tensions” between China, India, and Pakistan, potentially leading to nuclear war.

This was excised.

The assessment concludes that:

- The world is already experiencing the impacts of biodiversity loss, including crop failures, intensified natural disasters, and infectious disease outbreaks.

- Ecosystem degradation is occurring across all regions and ecosystems. The average size of monitored wildlife populations declined by 73% between 1970 and 2020.

Populations of vertebrate species have declined by an average of 68% since 1970. Freshwater ecosystem species populations have shown the largest losses, declining by 84% during the same period.

- The rate of extinction is tens to hundreds of times higher than the average over the past 10 million years. It suggests that a sixth mass extinction may be underway.

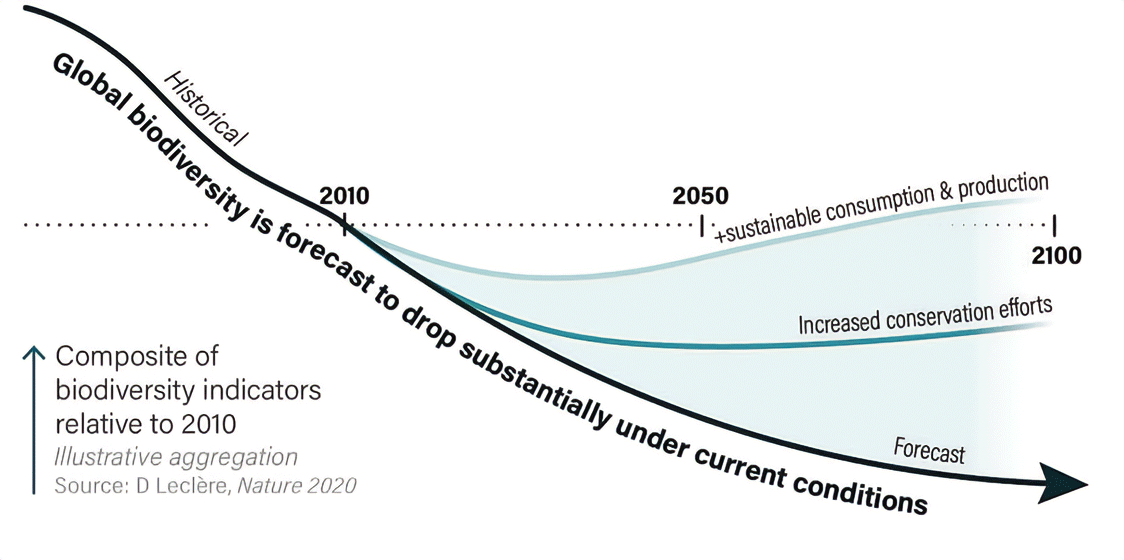

- With current trends, global ecosystem degradation is highly likely to continue to 2050 and beyond.

There is considerable uncertainty regarding the timing and pathways of ecosystem degradation, given the number and complexity of the drivers involved.

- Food production is the most significant cause of terrestrial biodiversity loss. As the global population grows to 9.7 billion by 2050, the impact of food production on natural systems will intensify, making it even more challenging to produce sufficient food sustainably.

To some, the conclusions may seem overly alarmist, but Anne-Marie Weeden, an environmental and climate security expert at the Royal United Services Institute, stated, “Don't let certain actors dismiss it as green scaremongering. This is a report prepared by the most sober and serious security analysts and intelligence experts across government.”

Weeden went on to say, “And the language and findings within the report may sound extreme, but that's just because we're just not used to having honest, grown-up conversations about what it means when we lose the very systems we depend upon for all human and economic life. “

Proposed solutions

The UK experts proposed several things that needed to be done to change the current forecast, mainly those proposed back in 2022 in the UN Convention on Biological Diversity’s Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework:

- Protecting 30% of global land and ocean by 2030;

- 30% of global nature to be under restoration by 2030;

- Mobilizing finance to close the funding gap of $700bn;

- Reducing risks from pesticide usage by 50% by 2050;

- Eliminating or reforming harmful subsidies by $500bn per year.

It would also be necessary to meet the Paris climate agreement target of limiting warming to 1.5 °C.

The 1.5 °C target refers to the long-term global average temperature rise above pre-industrial levels (1850-1900) by the end of the century, not a single year.

We've already warmed by about 1.36 °C due to human activity (as of recent data) and may see an average warming of 1.5 °C within the next few years, given the current trend.

Although often cited as a desirable goal, known as the 30x30 initiative, no one has ever put on a map the 30% of land and ocean that is supposed to be “protected”.

Only about 17% of land and 8% of marine areas are currently under some form of protection. Even then, in many cases, the effectiveness of that protection is in doubt.

Based on experiences of land grabs, loss of livelihoods, and human rights violations, some groups argue that the 30x30 target endangers the livelihoods, tenure, and customary access of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) to land and resources.

The term “fortress conservation” has been used to describe nature-centric conservation initiatives that have closed off access to the traditional territories and livelihoods of IPLCs, when they have been stewarding nature through generations.

Research also points to equal or higher levels of biodiversity in Indigenous-managed lands compared to protected areas in some regions.

Other critics describe the 30x30 target as a dangerous distraction from the underlying causes of biodiversity loss, which include rampant overconsumption.

In addition, early on in President Trump’s second presidential term in 2025, he pulled the US out of the 30x30 initiative.

Without U.S. cooperation and funding, achieving the goals outlined above will be challenging.

It looks highly unlikely that any of the solutions proposed by the UK government assessment will be implemented, so we can look forward to a world characterized by increasing instability and hardship.

Dr Stiles started in anthropology and archaeology, researching past and present natural resource use among hunter-gatherers and pastoralists, and later moved to the UN system, working on desertification control. In 1999, he began investigating wildlife trade, producing reports and publications for UN agencies, the IUCN, TRAFFIC, and various NGOs.