Editorial

Paradise Dreaming

By Zig Mackintosh

The 30/30 Biodiversity Plan

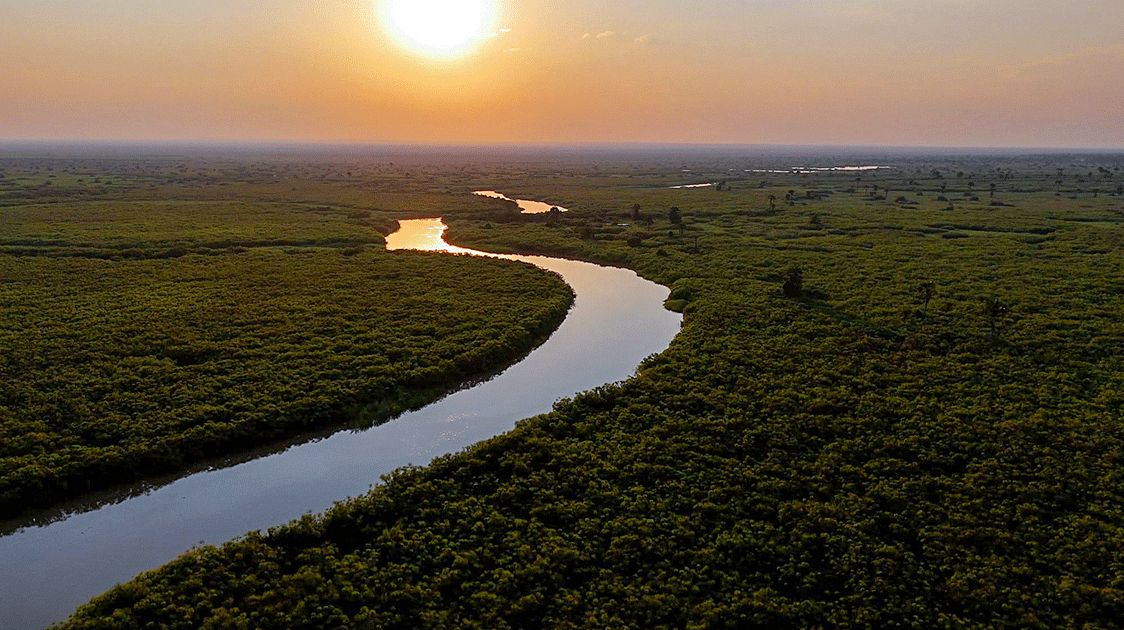

The 30/30 Biodiversity Plan, first proposed by the Campaign for Nature, is a global response to the alarming decline in biodiversity that threatens both wildlife and human communities. Currently, about 17% of the planet’s land and roughly 8% of its oceans are protected.

The initiative sets an ambitious goal: to conserve 30% of Earth’s land and water by 2030. This global conservation effort aims to safeguard natural resources, mitigate the impacts of climate change, and preserve the habitats and ecosystems that sustain biodiversity.

Goals of the 30/30 Initiative

The plan seeks to:

- Redefine “conserved” land, making it distinct from “protected” land.

- Transfer ownership and control of natural resources to indigenous and local communities.

- Combat invasive species that threaten ecosystems.

- Reduce nutrient and plastic pollution by at least 50%.

These are lofty ideals and worth striving for, but one must wonder how they intend to implement the plan and if they are overlooking strategies already in place and working.

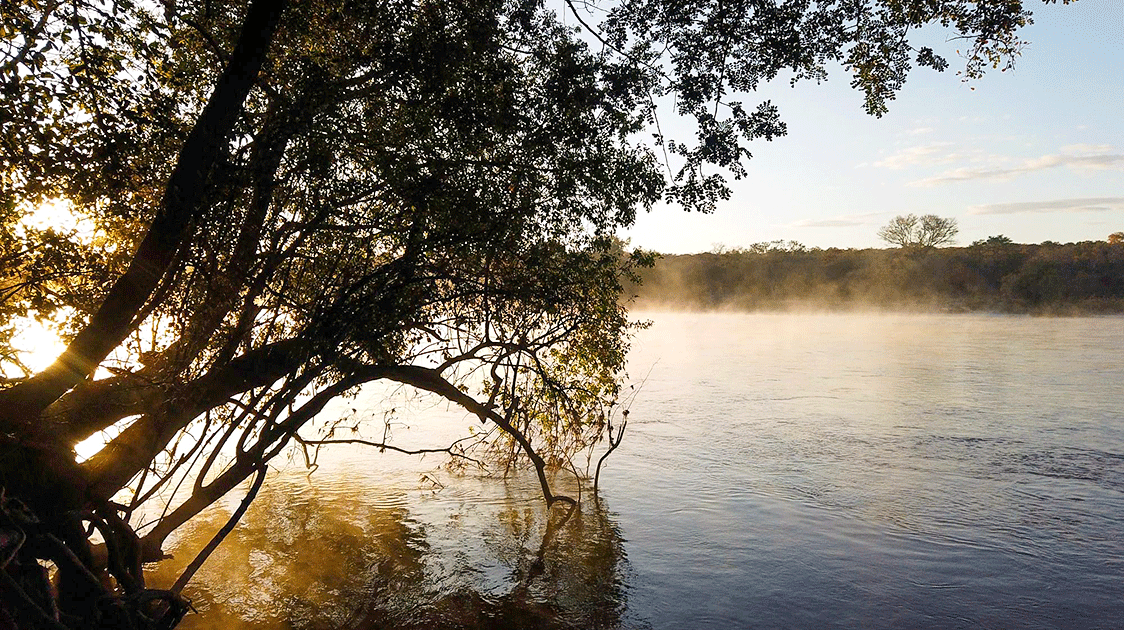

Lessons from Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM)

Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM), first launched in Zimbabwe during the 1980s under the CAMPFIRE program, offers a practical model for balancing conservation and livelihoods. Its core principle mirrors the 30/30 Biodiversity Plan: granting indigenous communities ownership of natural resources.

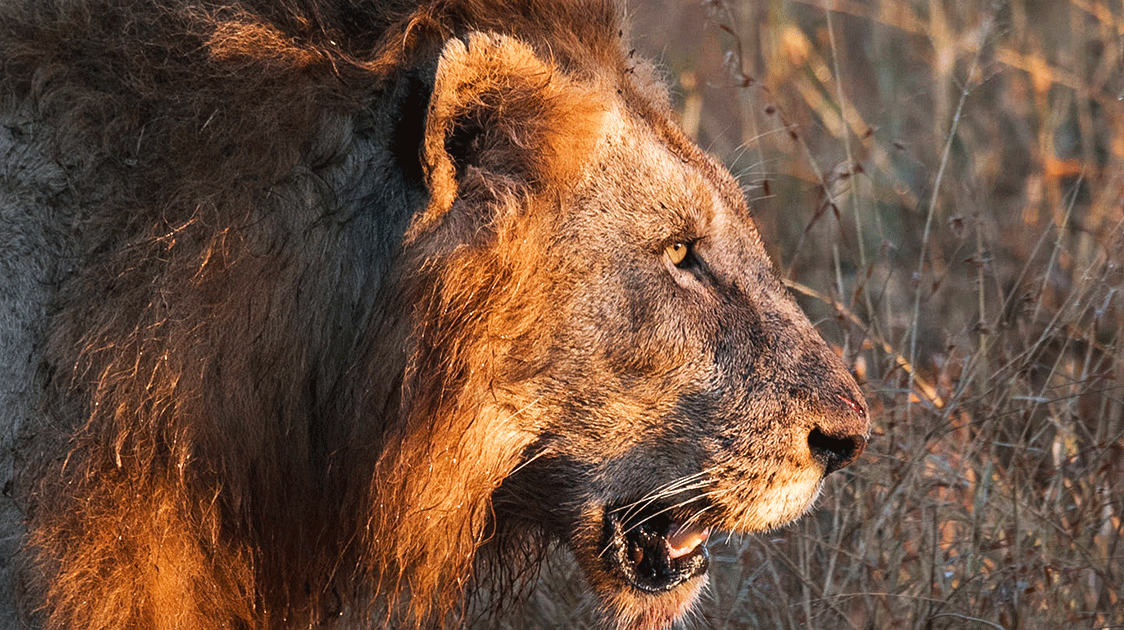

At the heart of CBNRM is safari hunting. While effective in giving wildlife a tangible economic value, safari hunting often clashes with the Western view of wildlife, which has been described as a “Disneyfied” perspective that rejects hunting. This clash is visible in the rising tide of Western anti-hunting legislation, including actions by agencies like the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Critics argue these measures lack common sense and fail to account for realities on the ground in Africa.

The Role of Livestock vs. Wildlife

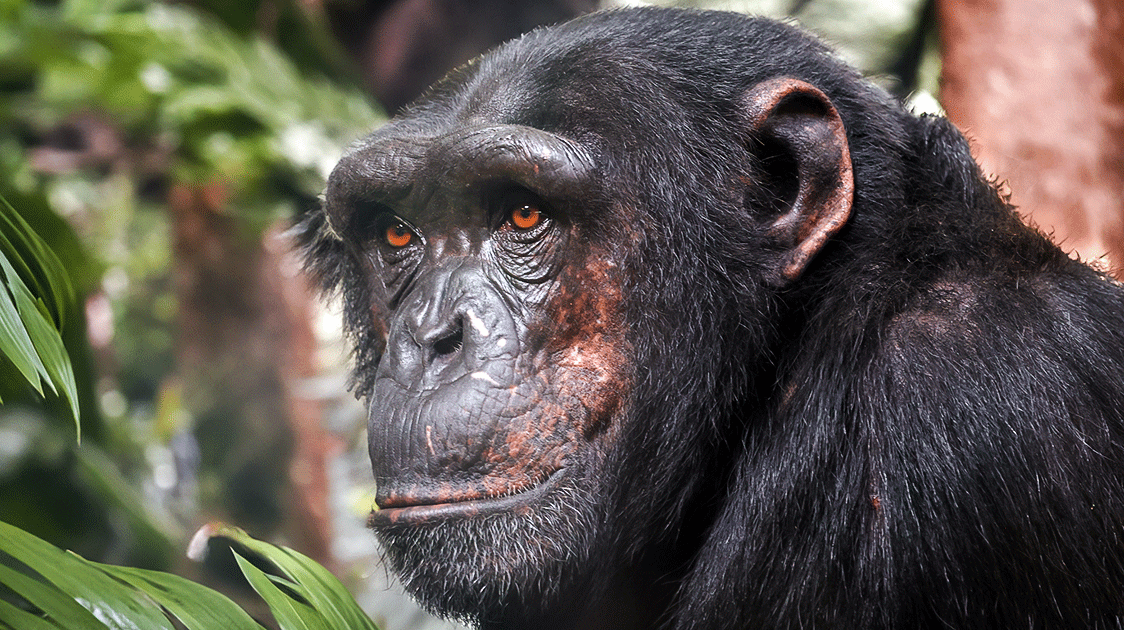

A PNAS study revealed that the total biomass of domesticated animals (livestock) and humans now far exceeds that of wild mammals. According to Greenpeace, humans and their livestock make up 96% of mammal biomass on Earth, leaving wild mammals at just 4%.

Why the imbalance? Because livestock can be owned, used, and monetized, while wild animals without economic value are often seen as a threat. Goats won’t eat children on the way to school or destroy a season’s crops overnight, but lions and elephants can.

If you want more wildlife, you must make it more appealing to indigenous people than livestock.

It is that simple.

Why Safari Hunting Matters for Conservation

Wildlife outside of protected areas in Africa risks becoming worthless if it cannot be sustainably utilized. Safari hunting provides both conservation incentives and vital revenue for community development and anti-poaching operations.

So, whose view should hold more weight, those who live with wildlife or foreign legislators and animal rights activists who think they know best?

The 30/30 Biodiversity Plan will remain a pipe dream; another expensive but ineffective eco-treaty, unless common sense prevails and proven African strategies like CBNRM are embraced.

FAQs

Q1: What is the 30/30 Biodiversity Plan?

The 30/30 Biodiversity Plan, launched by the Campaign for Nature, aims to protect 30% of Earth’s land and oceans by 2030 to safeguard biodiversity and fight climate change.

Q2: How does the 30/30 Plan involve local communities?

The initiative calls for ceding ownership and control of natural resources to indigenous and local communities, aligning with proven models like CBNRM in Zimbabwe.

Q3: What is CBNRM and why is it important?

Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM), pioneered in Zimbabwe in the 1980s through the CAMPFIRE program, gives communities a stake in wildlife, using safari hunting revenues to fund conservation and community projects.

Q4: What challenges does African wildlife face beyond poaching?

Major threats include illegal bushmeat trade, illicit logging, fish poaching, slash-and-burn agriculture, livestock grazing, and human encroachment. These pressures often harm ecosystems more than poaching alone.