Re-wilding a Wilderness: Coutada 9, Mozambique

By Neil Duckworth and Ed Rosenfels

In Mozambique, coutadas are officially National Conservation Areas specifically established for protecting fauna and flora through safari hunting and ecotourism. They are governed by the National Administration for Conservation Areas (ANAC). The coutadas are leased to private safari operators who manage the areas.

Coutada 9 is one of the original 15 coutadas established in 1959 and situated in Mozambique's Manica province, bordered by Coutada 13 to the South and East and Coutada 7 to the North.

Coutada 9 covers an area of 4 333 sq km (953 260 acres) and was initially leased to the Beira Tourism Agency, owned by the Pires family. Adelino Serra Pires documents the safaris of this era in his book "The Winds of Havoc".

In 1964 Coutada 9, along with eight other coutadas, were taken over by the Banco Nacional Ultramarino (Portugal's Overseas National Bank) and Safari Safrique company formed. Safrique was one the largest Safari companies in the world during the 60s and 70s, boasting some of the finest hunting Africa had ever known.

These glory years ended abruptly in 1973 with the start of the independence war. The country attained independence in 1975, but the outbreak of civil war in 1977 dashed any hope of the industry's revival. During the civil unrest, 1977-1992, Mozambique's National Parks and coutadas were decimated, with both sides killing wildlife for rations.

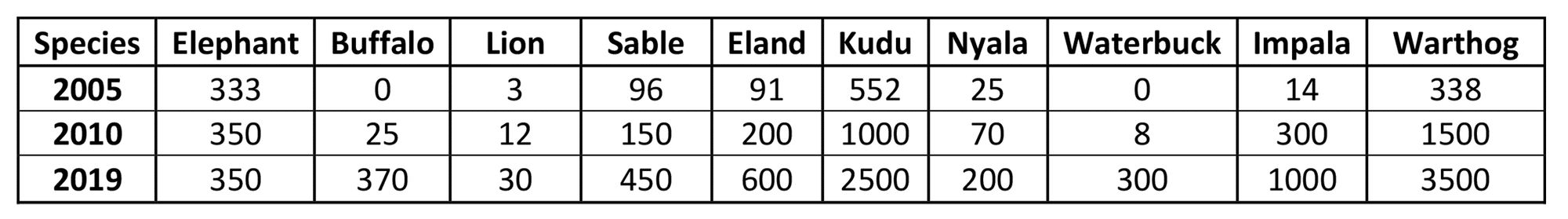

Safari hunting re-opened at the war's end, and Rio Save Safaris (RSS) began managing Coutada 9 in 2002. There were remnant populations of buffalo, kudu, zebra, eland, lion, leopard, and impala, but the jackal, hyena, wildebeest, and waterbuck had been eradicated.

The shareholders of RSS realized that a major rehabilitation of the area would be required if safari hunting were to become viable again.

Since 2002 four safari camps and three operation bases with workshops, storage facilities, and staff accommodation have been constructed, and over 1 500 km of roads have been opened.

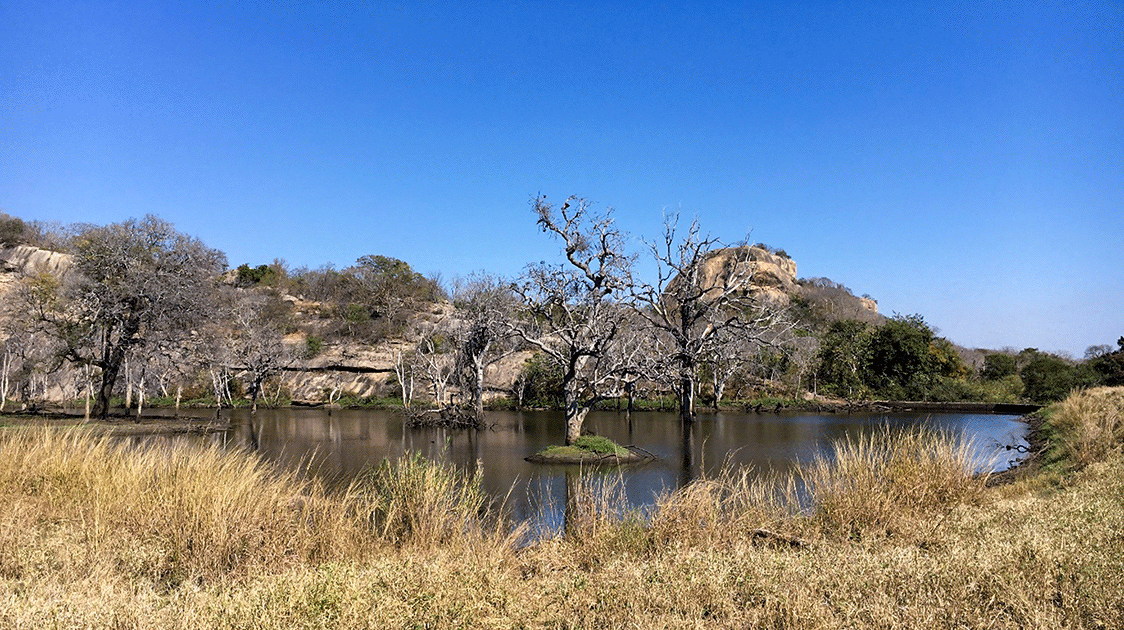

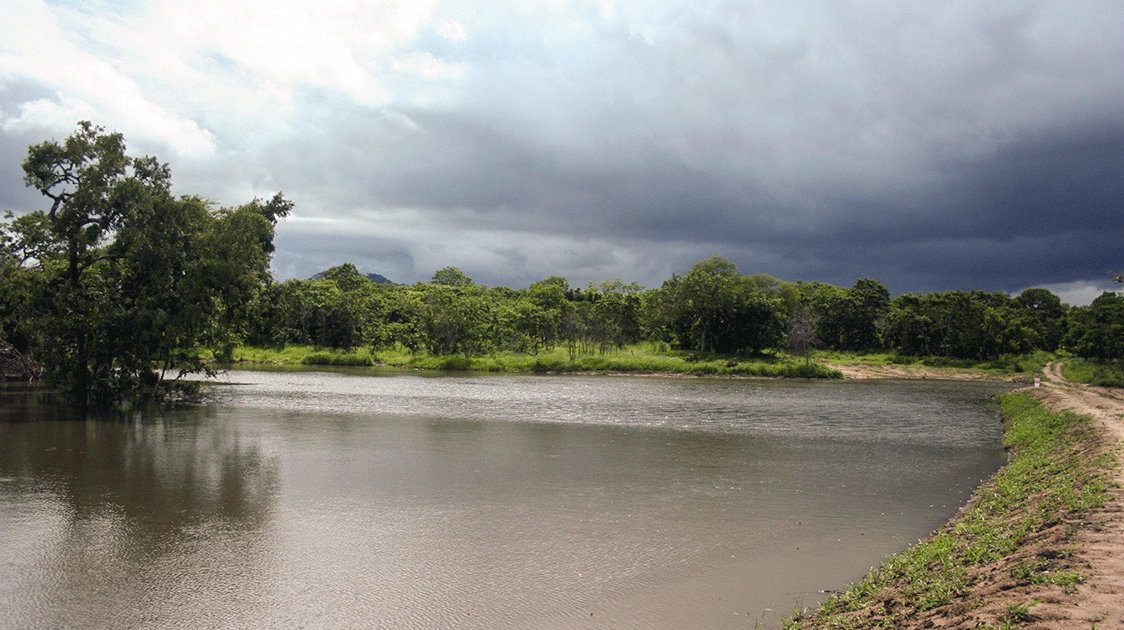

Thirteen dams have been built, numerous natural pans have been deepened, and their catchment areas have been improved to provide water for wildlife. Twenty-five boreholes have been drilled along with the construction of drinking troughs.

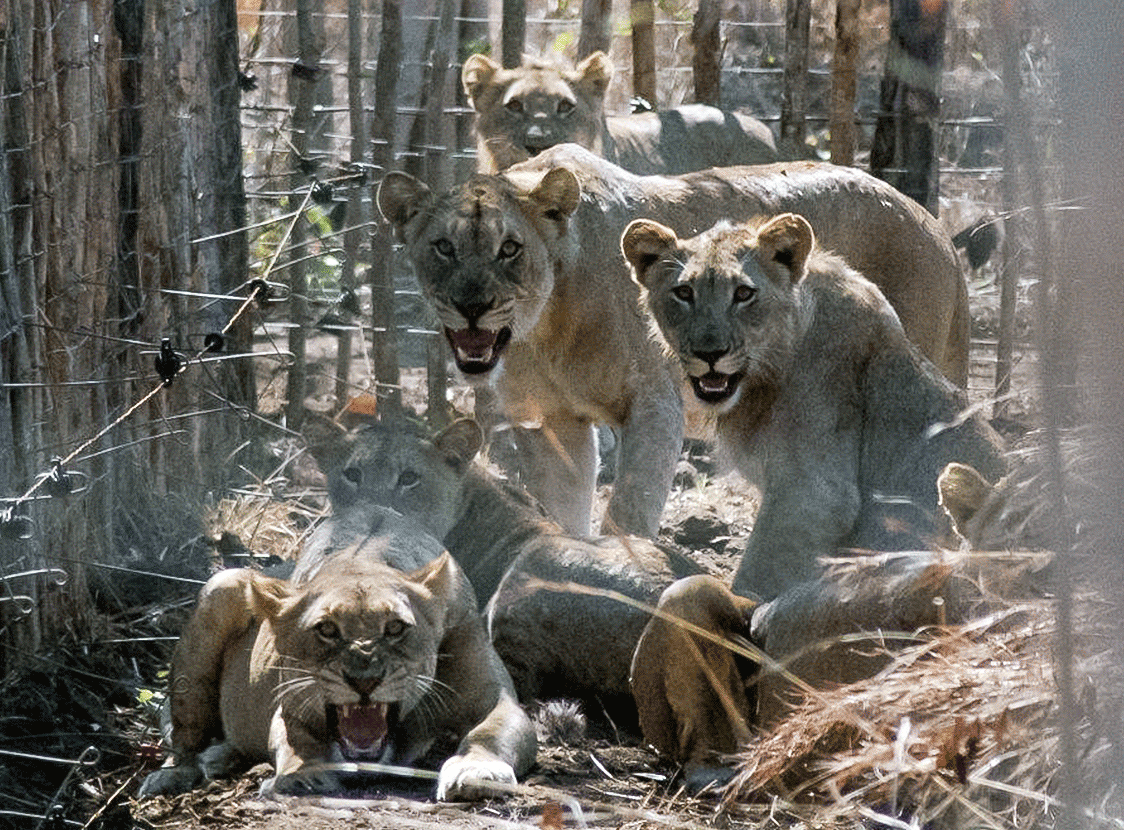

In 2009, 10 lions were introduced from South Africa's Pinda Game Reserve, Kwa-Zulu Natal. This was the first relocation to be carried out in Mozambique and the first outside of a National Park by a private organization. The lion population is currently over 50 animals.

In 2013, an agreement was made with Gorongosa National Park for an animal swap. Coutada 9 received 146 waterbucks in exchange for 20 Crawshay zebra and 40 elands. This deal was also a first for Mozambique, with a coutada providing animals to a National Park.

The waterbuck population in the coutada is currently over 600.

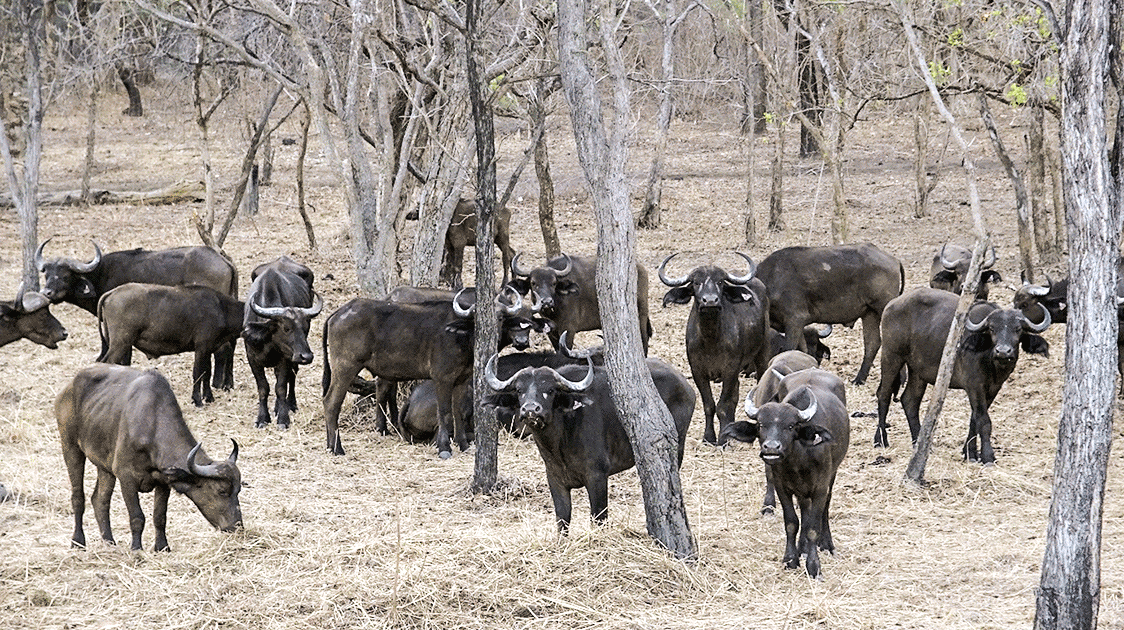

A healthy population of Cape buffalo was key to the success of Coutada 9. In 2015, 50 buffalo were caught in the Zambezi delta and moved to the coutada; in 2017 a further 200 were brought in. With government approval and sufficient funding, it is hoped that an additional 800 will be reintroduced. The current population stands at around 500.

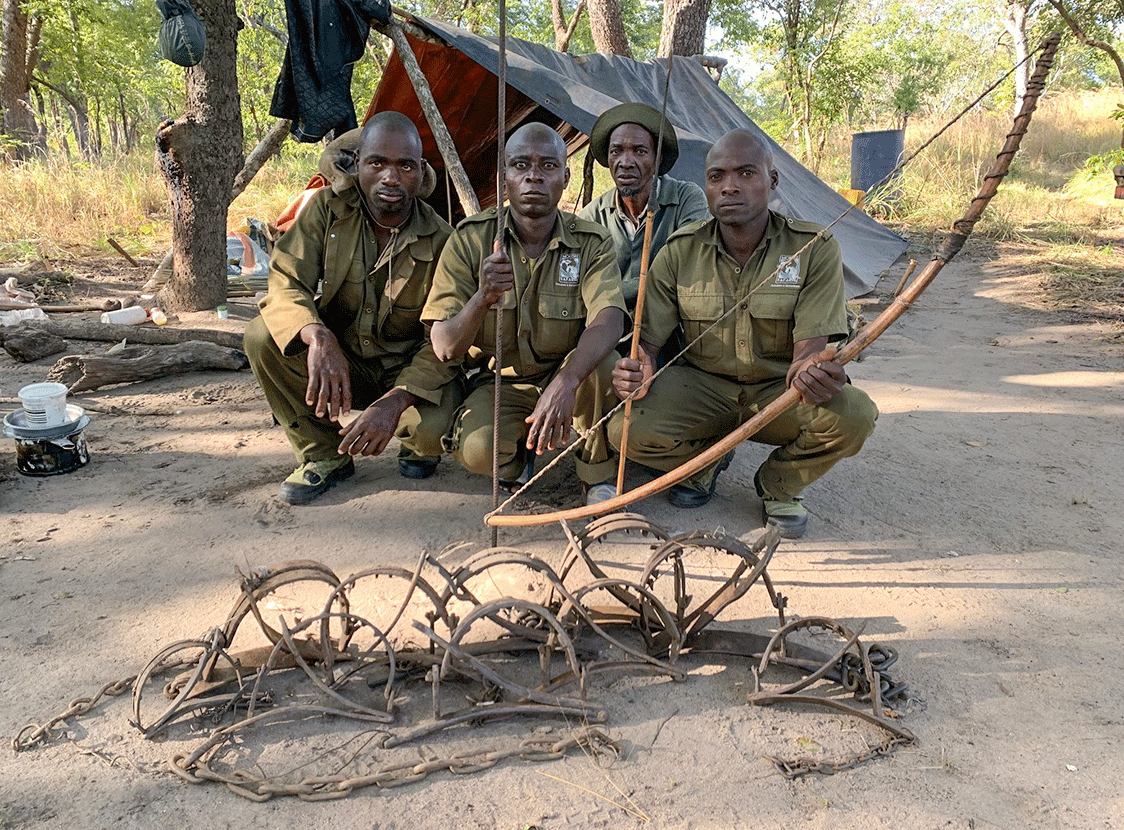

As the wildlife numbers have increased, so has the poaching threat; there are two forms ivory and bushmeat. Bushmeat poachers use homemade muzzle-loaders rifles, snares, bows and arrows, spears, axes and clubs to kill the game but the gin trap is most commonly used.

The purpose of a gin trap is to anchor the animal without killing it until the poachers can come and finish it off with spears. This way, the meat of the animal is kept fresh.

Gin traps are indiscriminate; many non-edible species are often caught in them. If an animal manages to escape, they are severely handicapped.

The ivory poachers generally use AK-47s but are often inexperienced marksmen and shoot indiscriminately at elephants without instantly killing them. The wounded elephant can suffer in pain for several days before dying and become very aggressive, making them a danger to human life.

Ivory poachers are much more aggressive than meat poachers and frequently shoot at the game scouts when confronted.

RSS currently has 65 game scouts, which equates to 1 scout per 65 sq km. Game scouts are recruited locally; many of the best are former poachers. This has several advantages:

- It takes them out of the poaching pool.

- They have an intimate knowledge of the area and know where the poachers are likely to operate.

- They have an interconnected network across all the villages and can gather intelligence during their time off.

- They know the poachers' modus operandi and equipment used.

- Their employment brings revenue into the local economy.

- Their status inspires others in the community to participate in the conservation project.

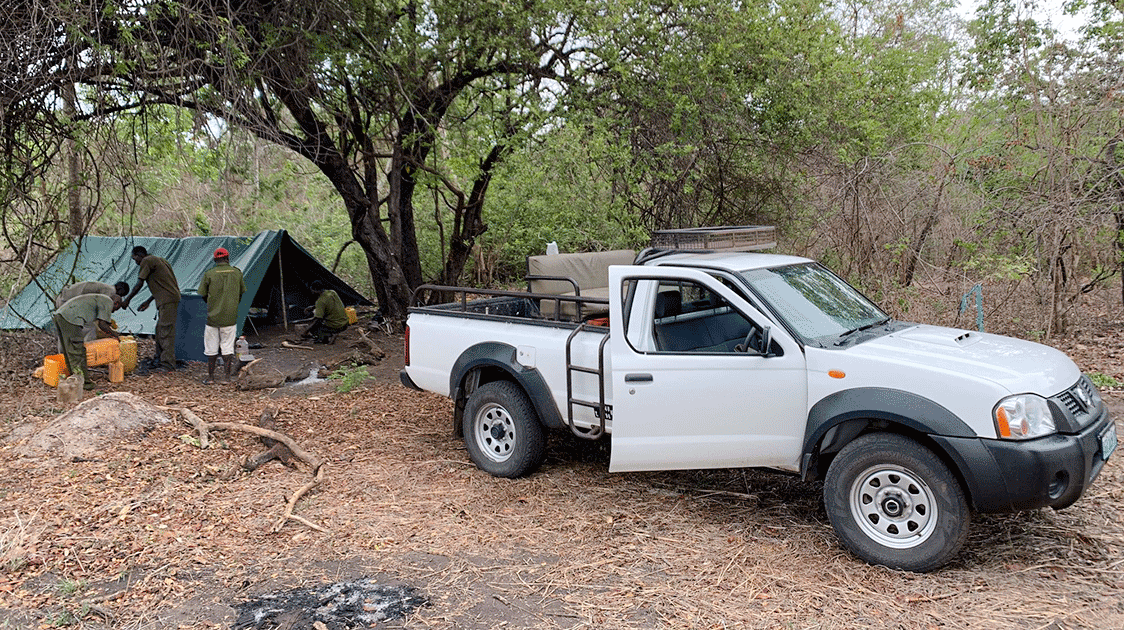

Recruits are given training in the relevant laws and regulations, equipment, and uniforms before they can be deployed as game scouts. Those recruits who show dedication and ability are trained to become team or "stick" leaders.

Sticks are deployed into areas with high game concentrations, such as near natural springs or dams, for 5 to 7 days. Patrols occur each day in different directions from the camp, which is the most efficient strategy to cover such a vast area.

When poachers are caught, the Area Manager is contacted, and everyone is taken to the local police authorities for criminal processing. Coutada 9 is so vast that there are three police stations, Macossa, Guro or Tambara, to take the poachers to, depending on where they are caught.

The whole process can take up to 6 hours which ties up the scouts, manager, and vehicle for the entire time, after which the scouts are dropped back at their post, a round trip of 100 km.

Incentive bonuses are paid for the capture of poachers and equipment. Captured gin traps are secured in a locked container and used to reinforce concrete foundations of new buildings.

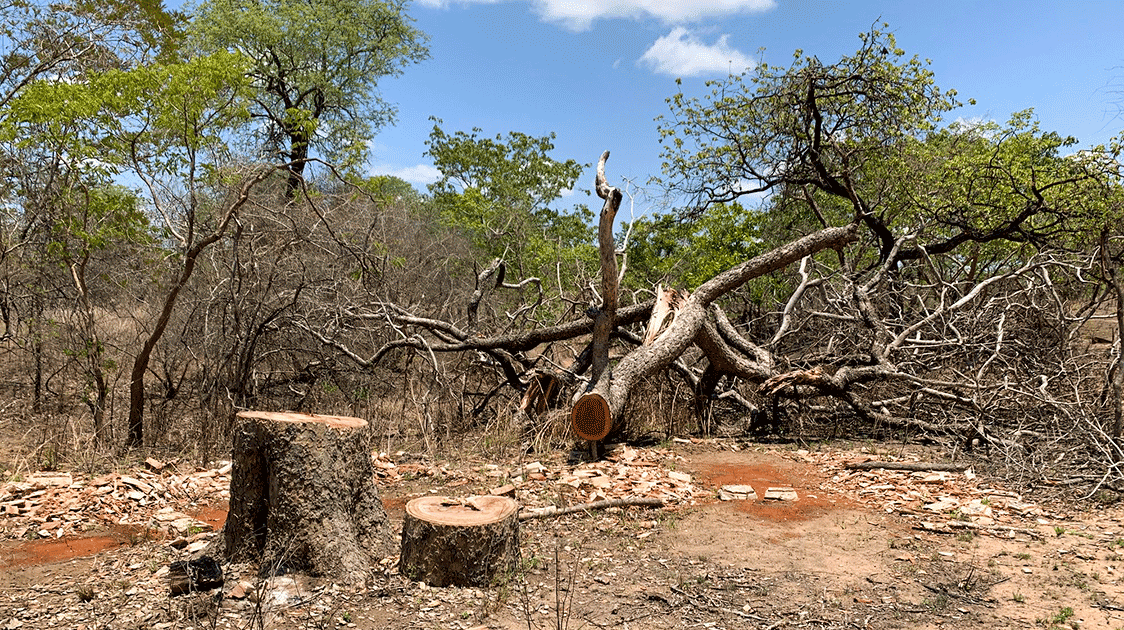

Honey gatherers remove large sections of bark from trees to make beehives, effectively killing those trees. They also cut down giant old trees just to access wild hives. This is not a significant concern in the coutada, but the honey gathering is used as a cover for meat and ivory poaching, and honey gathering has been prohibited.

Many large tree species in the coutada are targeted for illegal commercial logging, and the African mahogany tree is the main target. Over the years, three big logging operations have been blocked but not before the loss of over 100 large trees.

Illegal gold mining and panning in the coutada is a concern, with workers numbering in the hundreds. It is impossible to arrest everyone, and although government officials know the situation, nothing has been done to stop the activity. With illegal mining comes poaching to feed the workers.

Over ten thousand gin traps have been recovered in the past ten years, more than one hundred homemade muzzle loaders destroyed, nearly a thousand poachers, over two thousand miners and over a hundred loggers apprehended and handed over to the local government officials for prosecution.

Currently, each operator is responsible for anti-poaching operations within their management block of the coutada. Although there is collaboration, the long-term goal is to employ a dedicated anti-poaching manager to coordinate the different units.

The priority would be to double the number of scouts in the field; they will need training, weapons, radios, uniforms, boots, and camping gear. More patrol vehicles will also be required, and an allocation of funds towards fuel and maintenance.

The anti-poaching strategies also need improvement. At present SMART tracking devices are used, but ideally, one unit per stick is necessary. GPSs provide vital, real-time data on the scouts' position, distance and number of hours patrolled, which helps identify areas with higher poaching activity and need more patrolling. This anti-poaching tactic is in the trial stage, but excellent results have been realized.

Creating a Mobile Scouting Base (MSB) using a tractor and trailer will allow scouts to be self-sufficient and cover larger parts of the coutada, especially in areas where water is scarce. This will be beneficial in the more remote sections of the coutada.

Aerial reconnaissance is a very effective way to cover large distances quickly, and the microlight is the most efficient aircraft. The Dallas Safari Club has donated a bat hawk to the coutada, but funding will be needed to cover operational costs.

Tracking collars help monitor wildlife movement, which assists with protection. Two collars have been placed on lionesses and three on buffalo cows, and the plan is to expand the project to include elephants. By collaring matriarchs, breeding herds can be monitored. Young bulls are notorious crop raiders, and monitoring can reduce human-wildlife conflict.

General theft within the coutada is a problem; two radio repeaters have been stolen in the past, which is both costly and affects anti-poaching operations. Over the years, numerous solar panels and water pumps have been stolen from boreholes, affecting water provision for wildlife and RSS camps.

Coutada 9 has come a long way since 2002, but these achievements have come at a substantial financial cost, with over USD 5 million invested by the RSS shareholders. But more funding will be required for the area to reach its full potential, and the anti-poaching operations will need to be overhauled.