Botswana's Agricultural Fortress: Inside the Pandamatenga Project

Located in northern Botswana, a 160-kilometre electric fence encircles the nation's "food basket", but the project's ambitious expansion plans and wildlife controversies reveal the complex matrix of food security in modern Africa.

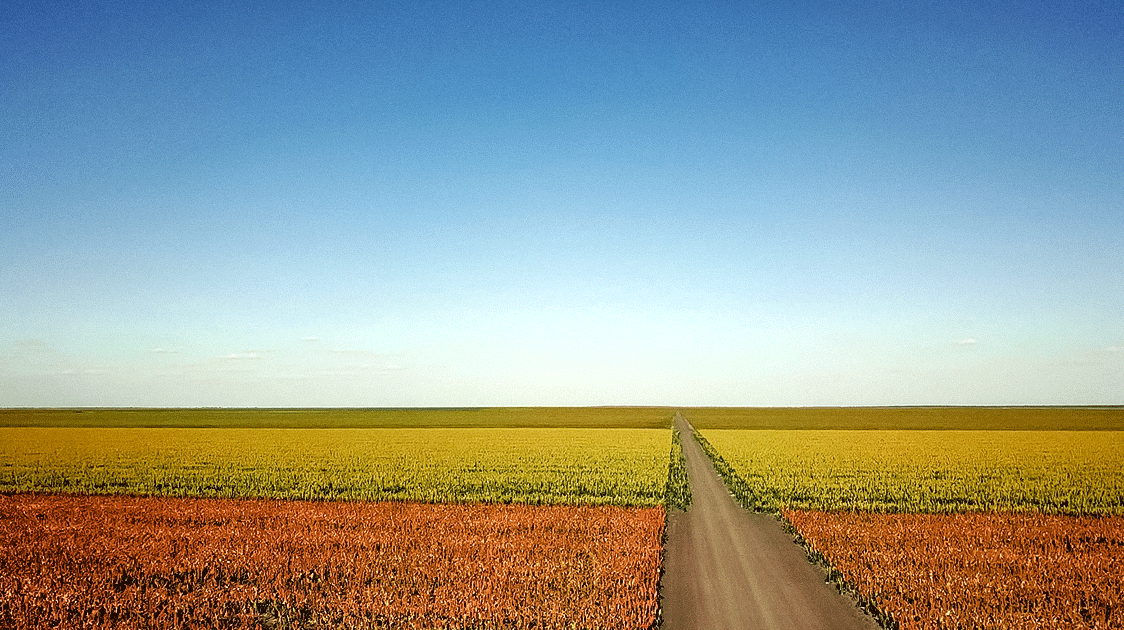

With fertile black cotton soils and an annual rainfall of 600 millimeters, the Pandamatenga farming project represents one of Africa's most ambitious attempts to balance agricultural development with wildlife conservation.

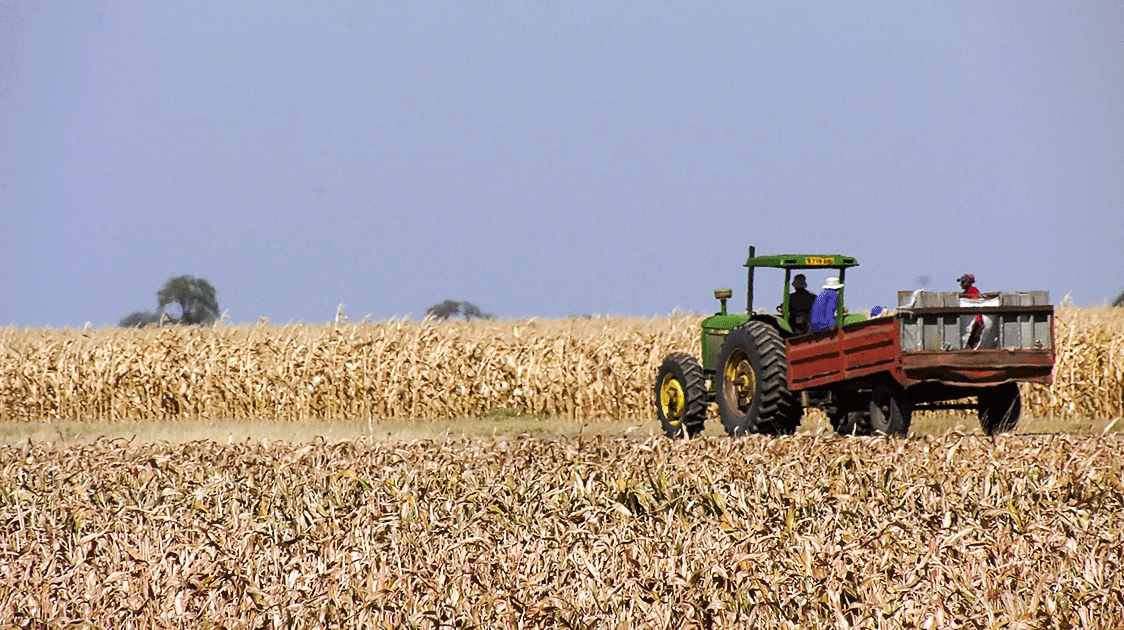

Since its inception in 1984, this vast commercial farming operation has evolved from a 25,000-hectare experiment into Botswana's primary grain-producing region, spanning over 200,000 hectares and generating millions of dollars in agricultural exports.

Yet behind the success stories of bumper harvests and technological innovation lies a prickly debate about the environmental and social costs of large-scale agricultural fencing in one of Africa's most wildlife-rich regions.

What began as a modest agricultural initiative has grown into an operation that produces the majority of Botswana's commercial cereal production. Recent infrastructure investments include 12 new steel silos worth USD 13.5 million and 22 state-of-the-art irrigation pivots covering 370 hectares.

The project's export portfolio now includes over 20,000 tons of premium mung beans annually, destined for markets in China, India, and Canada, generating approximately USD 10.5 million in annual export revenue.

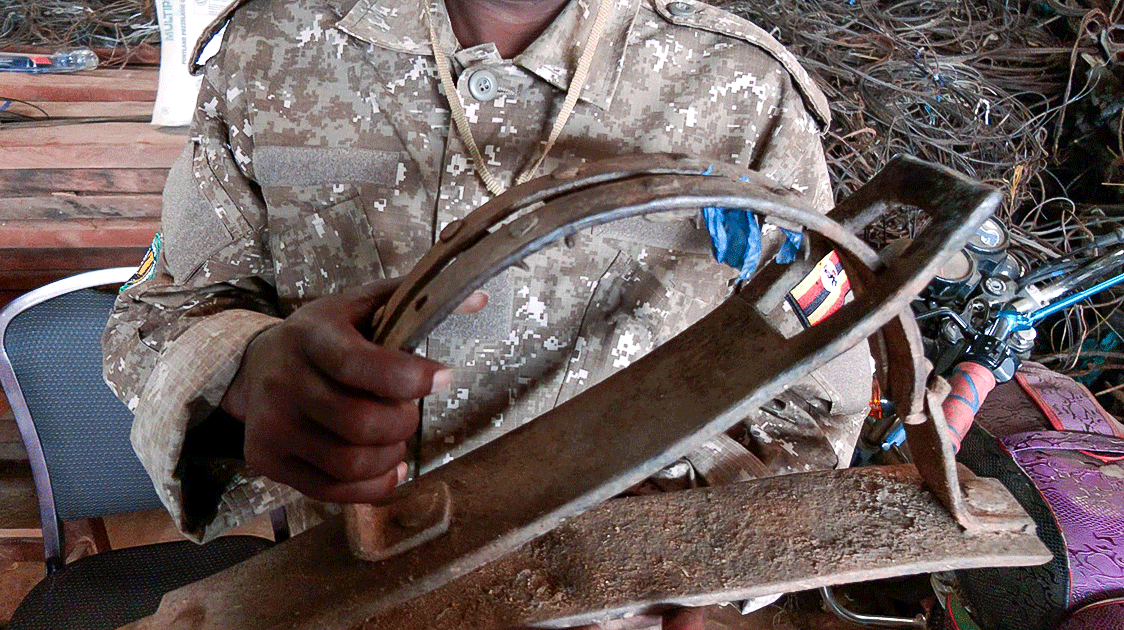

The Fortress Solution to an Ancient Problem

The heart of the Pandamatenga project lies in its anti-poaching operations approach to human-wildlife conflict, a challenge that predates modern agriculture in Botswana.

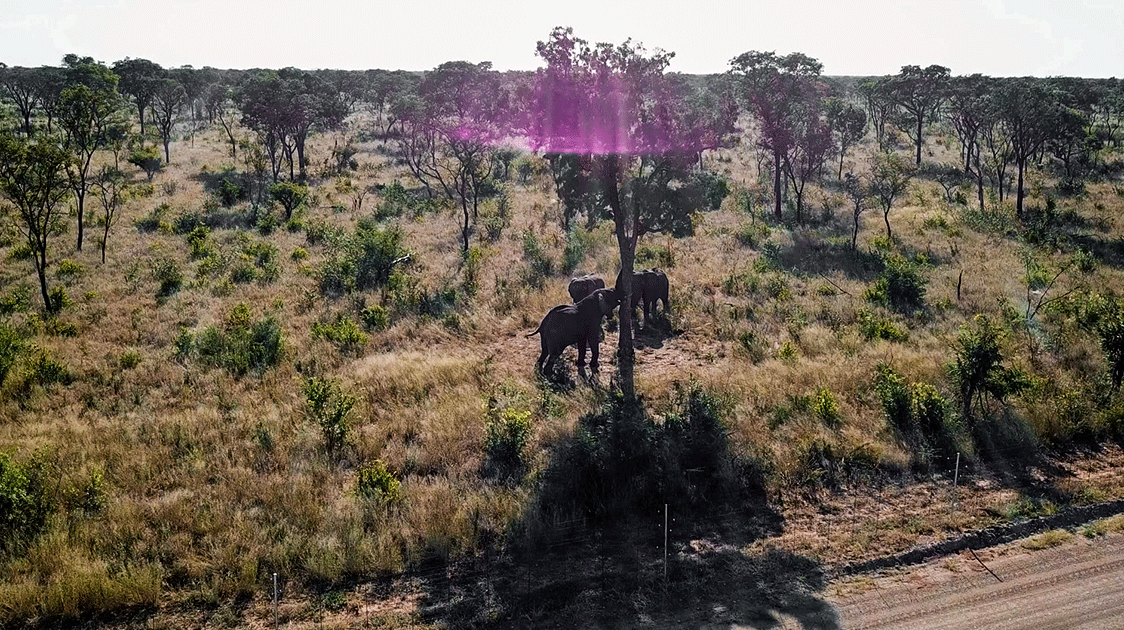

The 160-kilometer electric fence, erected in 2002, serves as both a protector and a symbol of the fundamental tension between agricultural development and wildlife conservation in southern Africa.

This fence, part of Botswana's broader veterinary cordon system that began in the 1950s, was designed to address a dual challenge: preventing the spread of foot-and-mouth disease from wildlife to livestock and protecting crops from elephants.

With a population of around 130,000 elephants, the scale of the challenge becomes apparent. In one instance, a particularly problematic elephant learned to push over fence poles, short-circuit the electrical wires, and then push down the fence to gain entry. This individual caused around USD 40,000 in damages over more than a year.

The farmers feared this elephant might teach others the same fence-breaching technique. When requests to shoot the problem animal were denied, the Botswana Department of Wildlife and National Parks intervened and successfully translocated the elephant.

Giraffe Issues

Giraffes present unique challenges for fence management. When bulls are present on both sides of the fence, they sometimes fight, causing damage to the fence. Male giraffes also break through the fencing to reach females on the inside.

Efforts to remove giraffes by temporarily lowering fence sections and driving them out have proven unsuccessful. The only practical solution is to dart and translocate the individual animals.

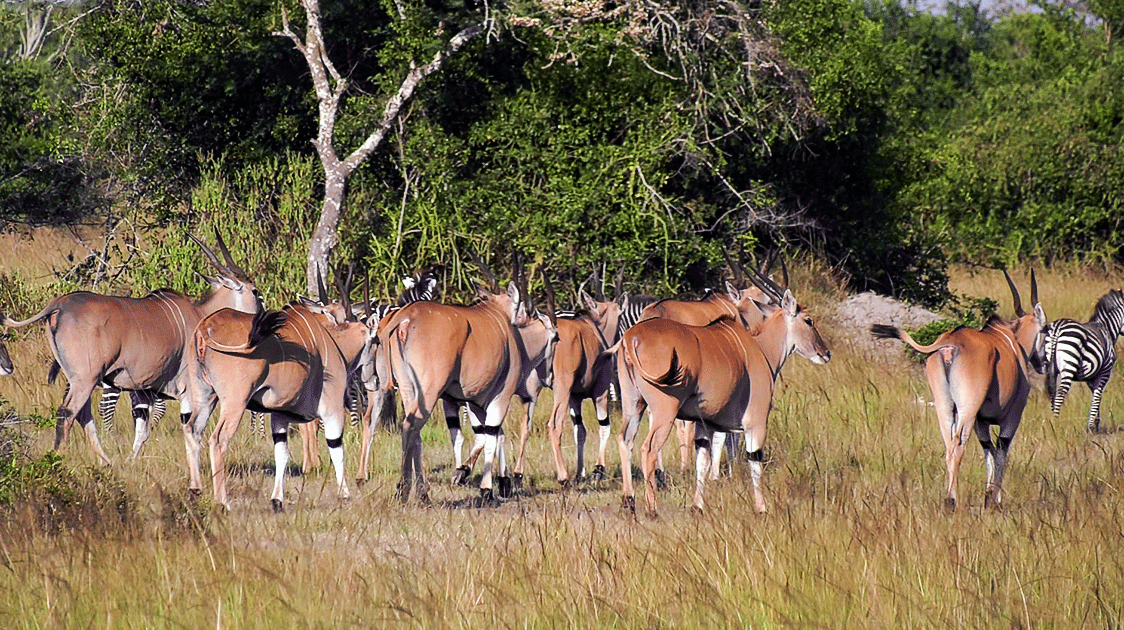

Wildlife Trapped Within the Fence

When the fence was erected, substantial wildlife populations became trapped within the agricultural area. These animals continued to breed and posed ongoing threats to farming production. Wildlife would hide within the remaining virgin bush during daylight hours, emerging at night to feed on crops.

Current wildlife management within the fenced area involves shooting animals in crop fields or translocating them outside the farming zone.

No compensation system exists for crop damage caused by wildlife, and when animals are shot, the meat becomes government property and is auctioned to local communities.

Beneficial Wildlife

Not all wildlife presence is problematic for farmers. Jackals are welcomed and protected because they control populations of rats and mice that multiply rapidly during harvest time, feeding on grain left in fields.

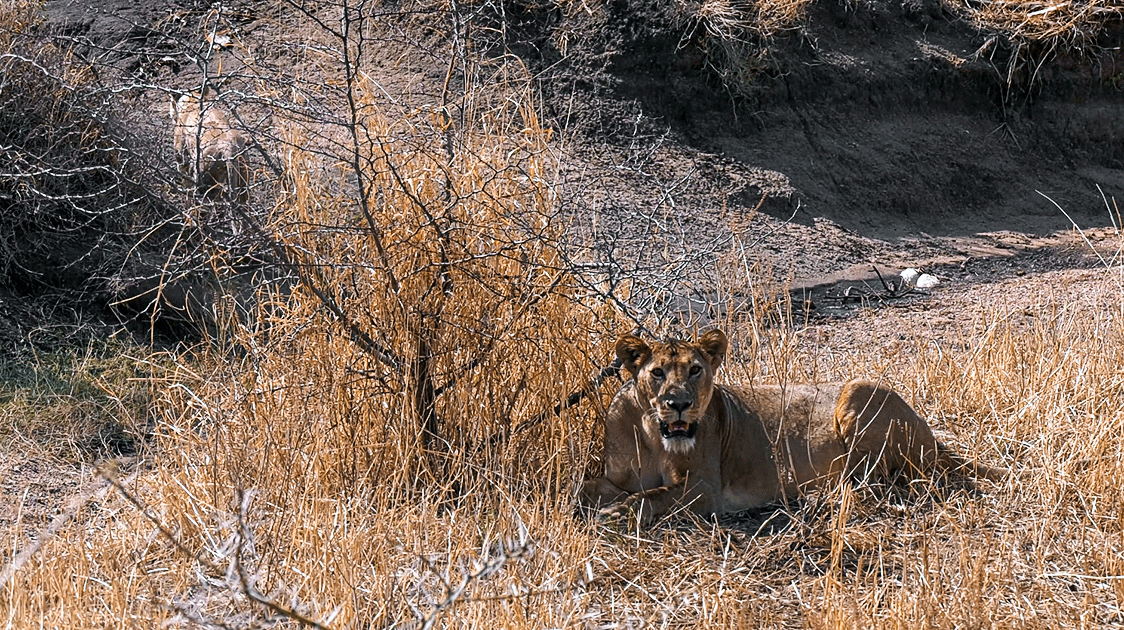

Similarly, lions and leopards are appreciated for controlling other wildlife populations that might otherwise damage crops.

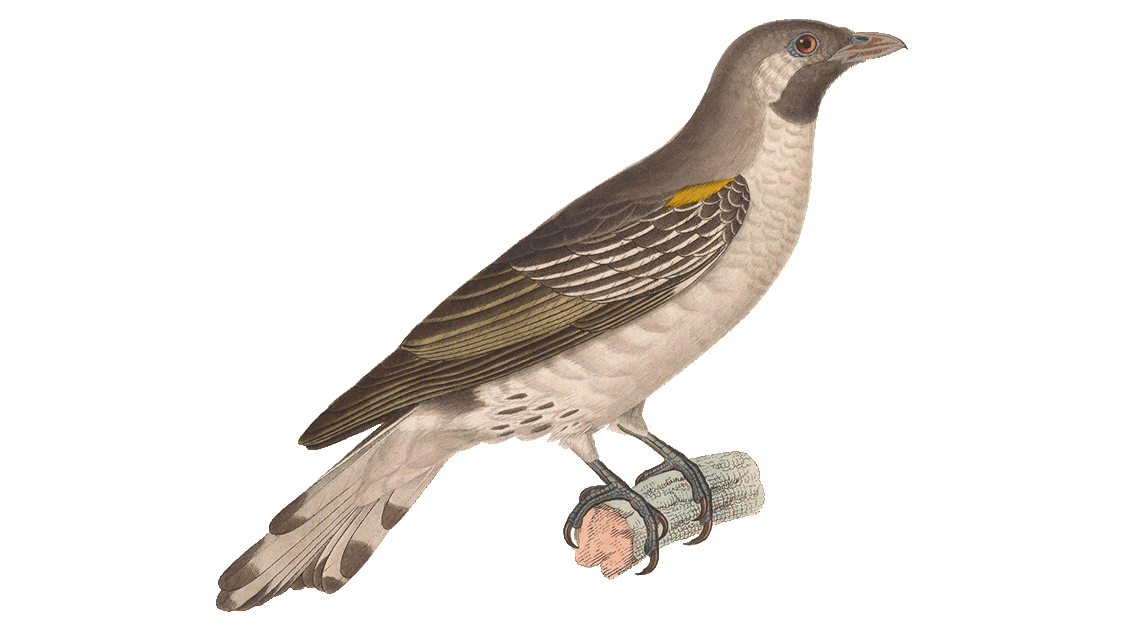

Bird Damage

Quelea birds represent another major agricultural threat. Flocks of five million quelea can destroy 50 tons of sorghum in a single day. Some roosting sites accommodate up to twenty million birds, making them capable of devastating crop production across large areas.

Collateral Damage

The fence solution comes with unintended consequences.

Between 1978 and 2003, wildebeest populations in Botswana's Kalahari declined from 315,000 to 16,000, and hartebeest from 293,000 to 45,000, largely attributed by researchers to fence-related habitat fragmentation.

Conservation organizations argue that veterinary fences have disrupted traditional migration routes and concentrated wildlife populations in smaller areas, intensifying pressure on animals and neighboring human communities.

Ambitious Expansion Meets Climate Challenges

The project's most ambitious phase lies ahead.

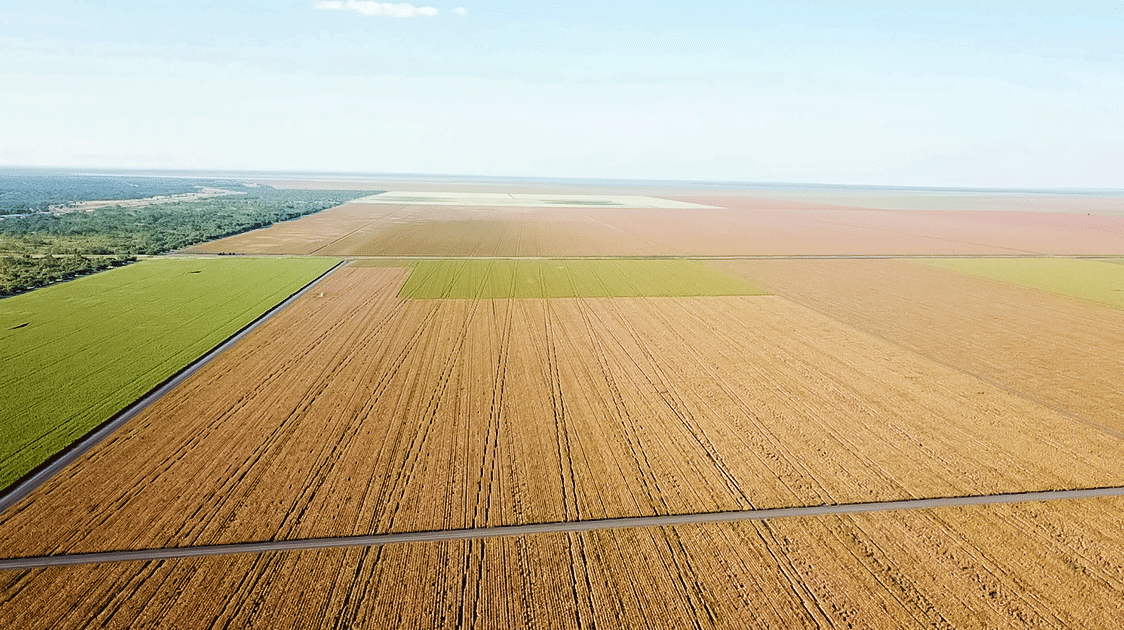

The Zambezi Integrated Agro-Commercial Development Project, approved by the African Development Bank with USD 1.37 million in feasibility study funding, envisions extracting 495 million cubic meters of water annually from the Chobe and Zambezi Rivers through a 104-kilometer pipeline system.

This massive infrastructure investment, estimated at USD 780 million, could irrigate an additional 25,000-35,000 hectares and create over 2,600 permanent jobs while targeting annual production of 160,000 tons of cereals and oilseeds plus 216,000 tons of mangoes.

The expansion comes at a critical time for Botswana's food security.

Despite allocating 46% of its land area for agricultural production, the country imports 80-90% of its food requirements, a dependency that has grown more acute with climate change.

The 2023-2024 season starkly illustrated this vulnerability when drought conditions led to harvest losses of 90-95% across the region, demonstrating why the government views irrigation infrastructure as essential for climate resilience.

Technology and Conservation Coexistence

The project's evolution reveals sophisticated attempts to reconcile agricultural intensification with environmental protection. Modern precision agriculture technologies, including GPS-guided tractors, drone surveillance, and soil sensors, have transformed farming operations.

At the same time, solar-powered elephant deterrent systems developed by Elephants Without Borders have proven effective in reducing crop raids without harming wildlife.

The EleSenses program uses solar-powered strobe lights to deter elephants. Surveys suggest this technological approach reflects a broader conservation shift from simple exclusion to active coexistence management.

Yet challenges persist. Botswana government reports indicate 45 people have been killed by elephants in recent years, with over 8,000 recorded human-wildlife conflict cases.

Researchers in Chobe District, which includes Pandamatenga, documented 1,212 crop conflicts and 1,013 livestock conflicts between 1994 and 2006. Recent surveys suggest continuing high levels of conflict that often exceed official government reporting.

Regional Model or Cautionary Tale?

Within southern African agricultural development, Pandamatenga represents a distinctive model.

Unlike South Africa's fragmented game fencing approach, which covers 17-20 million hectares in thousands of separate properties primarily focused on wildlife tourism and hunting, or Namibia's controversial "Red Line" veterinary cordon that maintains colonial-era economic divisions, Pandamatenga demonstrates integrated land use that addresses both food security and environmental concerns.

The project's success in crop diversification illustrates this integrated approach.

Beyond traditional crops like sorghum and maize, farmers now cultivate chickpeas, soybeans, wheat, and speciality grains for international markets.

Mung bean production alone generates over USD 10.5 million annually, with Pandamatenga-grown beans praised as among the highest quality globally.

However, critics note that even successful integration comes with tradeoffs.

GPS tracking data shows that fences create "impenetrable boundaries" for female elephants, disrupting migration patterns that historically allowed population regulation.

Male elephants demonstrate more border-crossing behavior, but only about 20% of the large KAZA (Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area) elephant population disperses freely between countries.

Economic Transformation and Social Impact

The project's economic impact extends far beyond agricultural statistics. Over the past decade, the National Development Bank has invested USD 124 million in farming, with USD 36 million specifically targeted to Chobe region commercial farmers.

This investment has supported production increases and technology adoption, including drone training programs and mechanized farming techniques imported from Australia.

Recent infrastructure developments underscore the project's strategic importance. Pandamatenga has been designated as a Special Economic Zone with 137,007 hectares allocated, including 84,500 hectares for commercial production, 12,400 hectares for subsistence farming, and 107 hectares for agro-processing facilities.

The timing coincides with the completion of the Kazungula Rail-Road Bridge, positioning the region as a potential export hub to broader African markets.

Yet questions remain about equitable development and community involvement. While 266 farming households directly benefit from commercial operations, the broader regional population of several thousand faces ongoing challenges from wildlife conflict and limited economic opportunities beyond agriculture.

The project's success in generating seasonal and permanent employment provides critical local benefits, but the scale of impact remains modest compared to the transformative investments in infrastructure.

The Path Forward

As Botswana pursues its Vision 2036 goal of becoming a high-income country, the Pandamatenga project embodies both the potential and the challenges of agricultural-led development in Africa.

The planned expansion through the Zambezi Integrated project could triple the current production capacity and establish Botswana as a significant regional agricultural exporter.

Success would validate the large-scale, technology-intensive agriculture model as a pathway to food security and economic development.

However, implementation faces significant hurdles. Climate change projections suggest a 30% yield decrease by 2050 without intervention, making irrigation infrastructure essential but expensive.

The USD 780 million cost of the Zambezi pipeline project represents a substantial bet on agricultural intensification at a time when many African countries are exploring more distributed, climate-resilient farming approaches.

The elephant question remains unresolved. While technological solutions like solar deterrents show promise, the fundamental challenge of accommodating 130,000 elephants alongside intensive agriculture will require continued innovation and compromise.

Recent policy changes, including Botswana's 2019 decision to lift its hunting moratorium, reflect growing political pressure to address human-wildlife conflict and highlight these contentious tradeoffs.

Conclusion

The Pandamatenga project is a testament to African agricultural innovation and determination. It transforms challenging terrain into productive farmland while addressing some of the continent's most complex environmental challenges.

Its success in producing high-quality export crops while maintaining elephant populations demonstrates that intensive agriculture and wildlife conservation can coexist, albeit with careful management and substantial investment.

Yet, the project's experience also illustrates the costs and complexities of such coexistence.

The fence protecting crops has altered ecosystem dynamics, the technology enabling year-round production requires massive infrastructure investments, and the wildlife enriching the region's biodiversity remains a source of ongoing conflict and controversy.

As African countries grapple with food security, climate change, and conservation challenges, the Pandamatenga project offers both inspiration and caution.

Its agricultural productivity and export development achievements provide a blueprint for large-scale farming in challenging environments.

Its ongoing struggles with wildlife conflict and environmental tradeoffs remind us that even successful development comes with difficult choices and uncertain outcomes.

The story of Pandamatenga is still being written. The next chapter is likely to be determined by whether the ambitious Zambezi irrigation project can be successfully implemented and whether innovative approaches to human-wildlife coexistence can be scaled up across the region.

Behind the electric fence, the delicate balance between conservation and cultivation continues crop by crop, season by season.