The Decimation of Tanzania's Acacia Forests

By Hanks's Voice

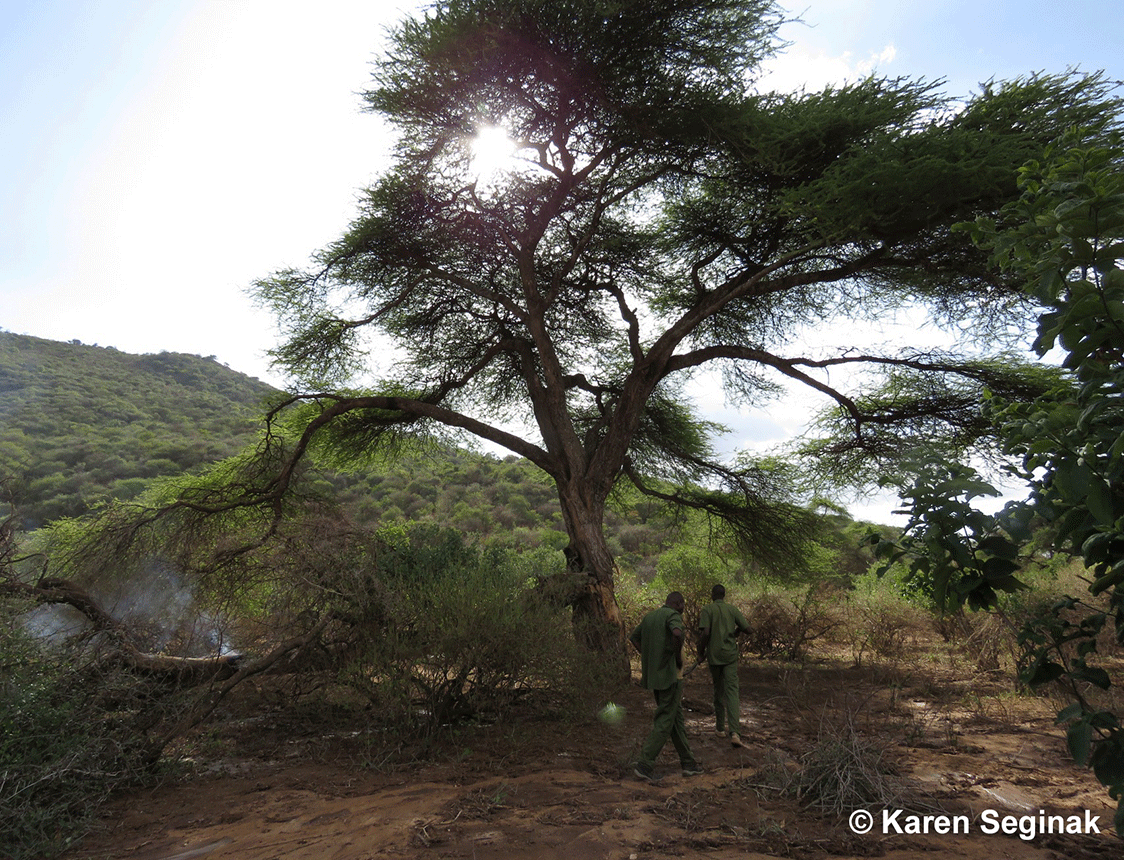

The anti-poaching rangers of Michel Mantheakis Safaris and accompanying government game scouts patrol their Maasailand, Tanzania hunting area every day of the week, all year round, and are especially vigilant at night and in the wee hours of the morning. Some are perched on the sides of mountains or high spots as lookouts, while others await directions from them to close in, lower, on foot.

What are they looking for? Smoke. Rising tendrils from burning wood could indicate charcoal poaching.

The hunting land they protect is a designated game-controlled area, so various human uses are permitted by the Maasai pastoralists who live on adjacent community lands. Herders may build fires for cooking or heat whilst tending their grazing livestock.

But only fires built with collected dead, downed wood are the traditional and only legal way to do so. Charcoal production is not permitted, nor was it ever a favored practice.

However, the poaching of trees to produce it now as an illegal cash crop is tragically plaguing conservation efforts and is a problem that straddles forest and energy sectors, impacting wildlife and communities, both urban and rural.

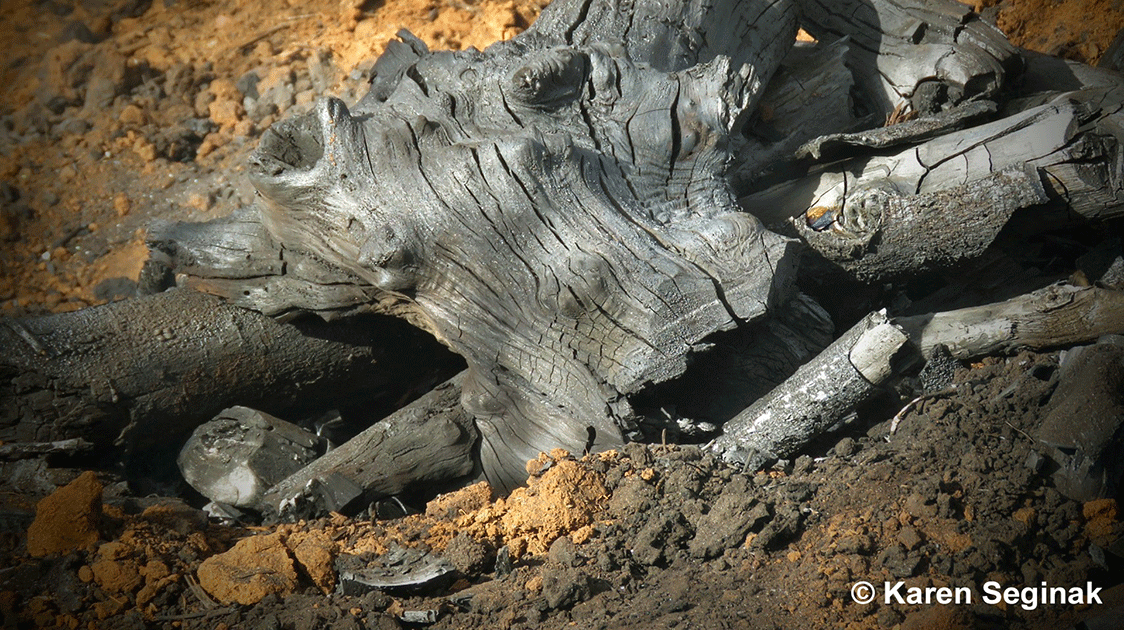

Producing charcoal is labor and time-consuming. Live trees are selected, especially large, mature acacias, sometimes as old as a century.

Any trees chosen must first be "mysteriously" killed since cutting live trees in the area is a law violation itself. Poachers dig to expose the tree's base, then pound nails into its roots to kill it. Small spot fires are started along the trunk to hasten its death.

Once the tree begins to weaken and fall over, it's easy to claim, dishonestly, that it was found dead.

When felled, the tree is chopped into manageable-sized pieces. One can make a reasonable guess as to the gender of the perpetrators by the size of the segments, with the smaller, lighter ones attributable to Maasai women.

Women are often the preferred charcoal producers, as they can potentially more easily illicit sympathy by manipulating anti-poaching staff with their emotions than Maasai men when caught.

The charcoal is produced by burning it in traditional earth mound kilns constructed on the spot. Logs are crisscrossed, set afire and covered with soil, wherein a minimal supply of air transforms the burning wood into charcoal via pyrolysis.

Unfortunately, this is not a very efficient process.

Much wood is converted to ash instead, as efficiency rates for these kilns range from only 8 to 23%. The inherent wastage in this process results in charcoal consumers ultimately using 4 to 6 times more wood than consumers of firewood.

Kiln areas also leave permanent ecological footprints, as the soil is often sterilized in such high heat. Although this is estimated only to affect about 3% of the area harvested, the effects can be significant when considered cumulatively.

Most of Tanzania's population primarily depends on wood fuel, charcoal, or forest residue for household cooking. Charcoal is the most popular in urban homes throughout most Sub-Saharan African countries, as it is easier to transport and store, fits smaller city stoves better, and is not liable to deterioration by insects or fungi.

Average household use typically ranges from 30-50 kg per month. In a city the size of Dar Es Salaam, for example, the daily demand rate can be as high as 24,000 sacks weighing 50kg each.

Legal charcoal production and selling options exist in certain places and land designations in Tanzania. In 2014, it generated at least USD 1 billion in annual revenue. But the illegal market is also significant and is estimated to be 30 to 90% of production, depending on the region.

Charcoal is relatively easy to hide in the buckets pastoralists commonly carry, it can be easily stashed secretly in the weekly market areas and transported across borders by motorbike, readily avoiding checkpoints.

Charcoal demand and usage increase with increasing human populations. For each 1% increase in urbanization, there is an estimated 14% increase in charcoal consumption.

In 2009, up to 30% of all deforestation in Tanzania was due to charcoal production. This is a genuine threat to the long-term persistence of natural forests, as, for the most part, trees are not being replanted or are done in plantation style.

This loss of mature tree cover affects rain filtration through the forest canopy and decreases surface infiltration, thereby increasing surface runoff and sedimentation in streams.

Important shade sources for everything from insects to giraffes and the pastoralists' livestock are lost, and nest or roost trees and water catchments are destroyed. Weaker tree regrowth, decreased soil fertility, and reduced agricultural productivity result.

All of which ultimately can increase poverty.

The Longido area is a critical trans-national migratory route and dispersal area along the Tanzania/Kenya border for many species, including elephants. It is also one of the driest areas in Tanzania. A region with increasing rates of agricultural cultivation and livestock grazing, both of which, when done in excess, exacerbate and are significantly impacted themselves by charcoal poaching deforestation.

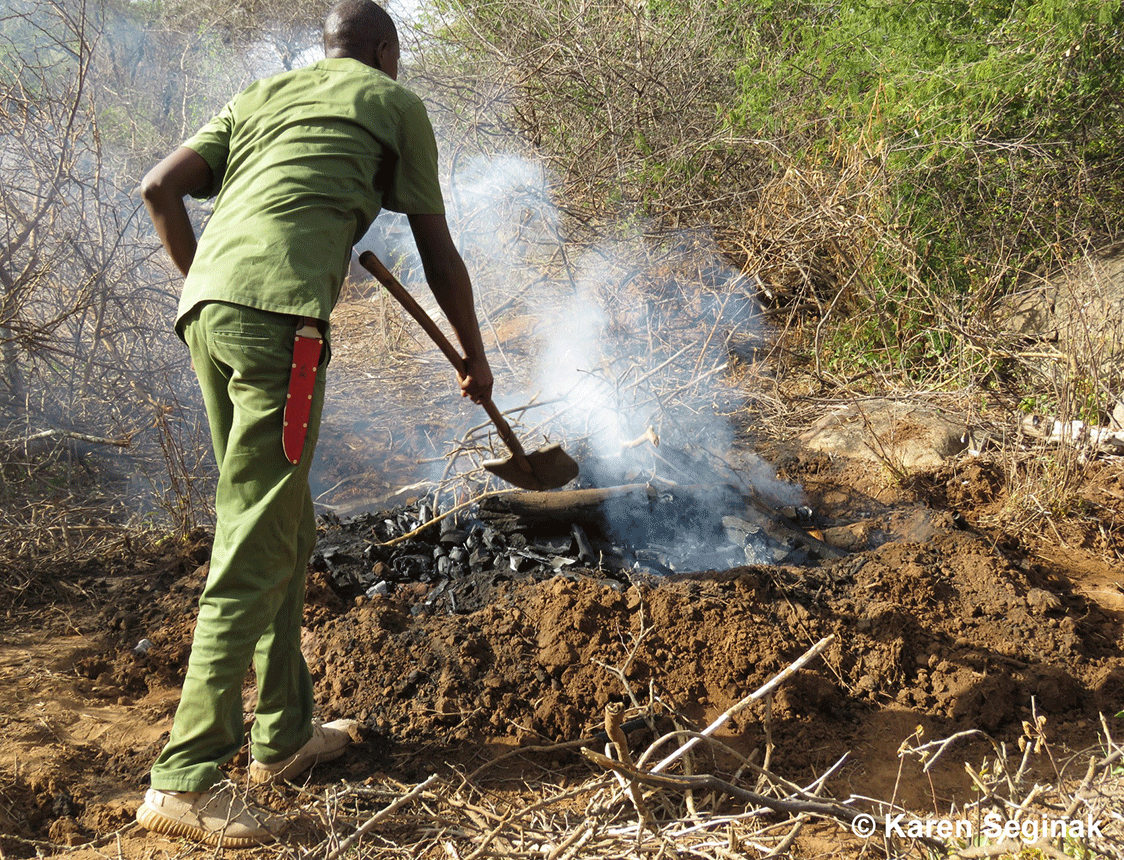

When anti-poaching patrols find kilns, they destroy them, which is hard, hot and smoky work. And incredibly frustrating as the environmental damage is already done. And will take decades to repair, even, if possible, as the best charcoal-producing trees are slow growers vulnerable to overharvest. It's truly painful to witness such a waste of resources rangers are battling to protect.

But when the charcoal poachers, who are destroying these ecologically essential acacia forests, flee upon detection and are absent, the rangers must make their presence known in this way.

Ancient civilizations used smoke signals to warn others of danger, but today, these rangers are snuffing out the smoke of illegal charcoal production. Smoke from a terrible sort of poaching signals the threat to the present and future of Africa's forests, wildlife, climate and people.

The author wishes to thank Michel Mantheakis Safaris' staff for graciously hosting her and sharing their knowledge of their challenges while combating charcoal poaching.

Special thanks to Michel Mantheakis, an Executive Committee member of the African Professional Hunters Association and Chairman of the Tanzania Hunting Operators Association, for his steadfast, lifelong commitment to anti-poaching efforts in all areas he outfits.