What Is It That We Are Trying to Achieve?

We have been successful in shaping the environment to best suit our needs. Agriculture and industrialization evolved through the quest to make life more comfortable, but these activities have impacted the biodiversity of ecosystems around the globe.

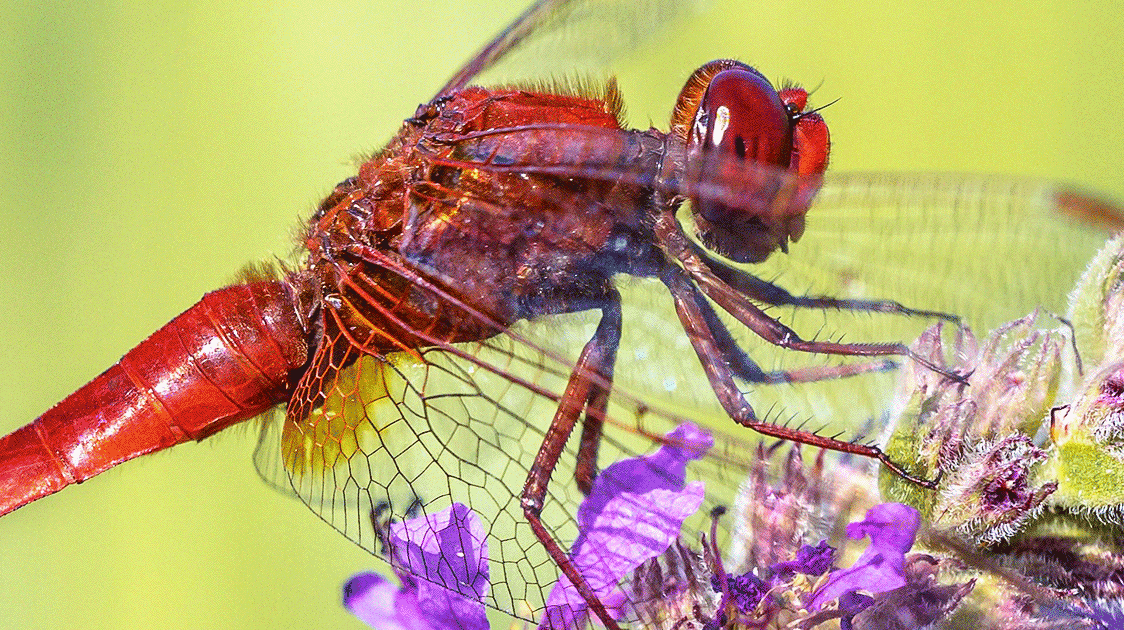

Biodiversity is an essential indicator of ecological functioning. The decrease in biodiversity is strongly correlated with reductions in ecosystem stability. The emotionally driven preference for one species over another based on bias and unfounded rationale has been and still is a cause for loss in biodiversity.

Over fifty years ago, American policymakers attempted to correct this bias with the 1966 Endangered Species Preservation Act, the first U.S. endangered species legislation. With the expert guidance of scientific bodies, the Secretary of the Interior was responsible for listing threatened species.

The decisions to list species were and still are based on "the best scientific and commercial data available." But this is problematic as there is no clarity as to what "best" is in relation to or what standard they hold their decision-making to.

The 1973 Endangered Species Act intended "to halt and reverse the trend towards species extinction, whatever the cost." The concept was noble and was championed as "the most comprehensive legislation for the preservation of endangered species ever enacted by any nation."

The criteria of eligibility are ill-defined and not standardized across all species.

In 1982, Congress amended the act, including making the listing process "strictly science-mandated." The idea was to remove "irrelevant" economic impact analysis and to make listing determinations based solely on species' biological conditions.

But science alone cannot and should not make policy decisions.

Assessing the risk of extinction is a purely biological problem, whereas setting conservation priorities requires more subjective considerations. Removing the economic value of a species renders it worthless.

In 1988, concerns with extended listing delays resulted in the power to list species as threatened or endangered being invested in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Endangered species are classified as such if they are "in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range."

Species are threatened if it "is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range."

Five factors are considered:

- "the present or threatened destruction, modification or curtailment of its habitat or range."

- "overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes."

- "disease or predation."

- "the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms."

- "other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence."

These factors are generalized criteria that do not provide a standardized classification method for different species. There is little relationship between listing status and vulnerability.

Many unlisted species are in great danger of extinction, while those listed species are not always the most vulnerable.

No standard exists to distinguish threatened from endangered.

The agencies are free to pick whichever they prefer, given the political climate of the moment.

The lack of standardization of listing has led to political lobbying from interest groups of all ideological persuasions, with political parties' pressures often influencing the listing process.

Repeated investigations by the General Accounting Office have consistently found that listing decisions are more politically driven than based on science.

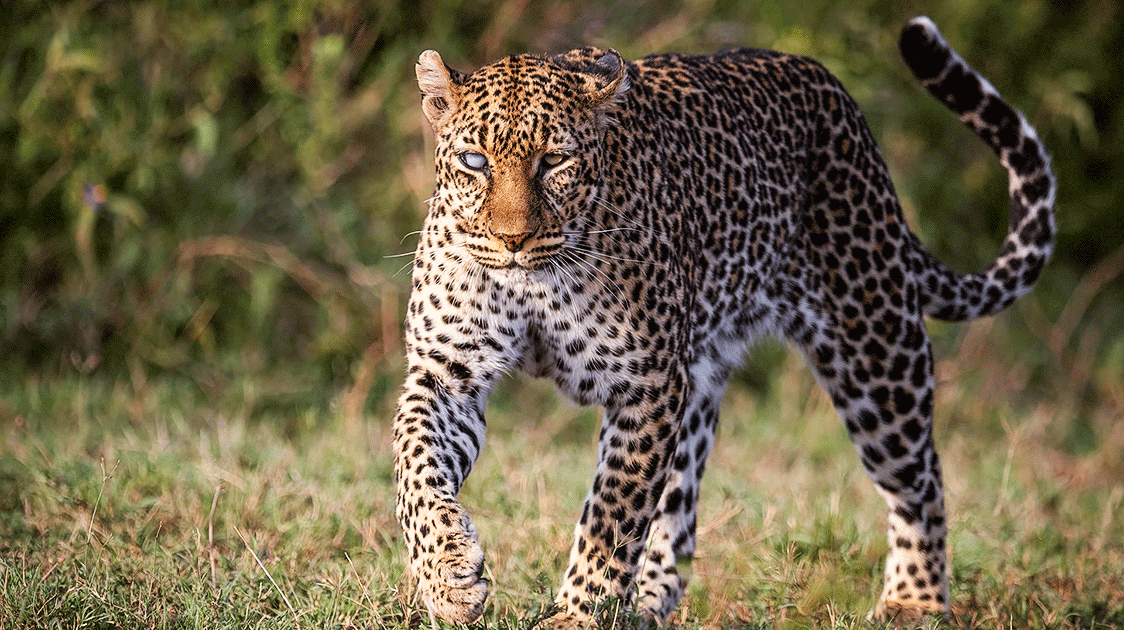

This politically bias listing system causes a massive problem of selection charming species over those that may be more valuable to their ecosystems, thereby forsaking the Endangered Species Act's "goal of protecting all species equally based on threat alone."

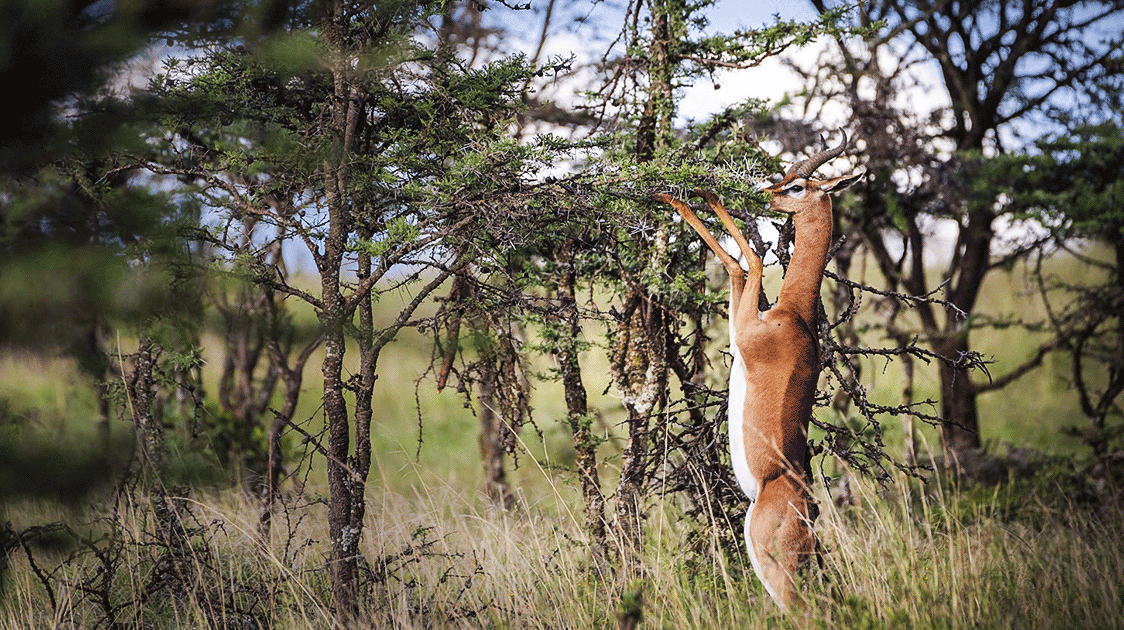

By its admission, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service believes the conservation benefit of listing domestic species is generally much higher than listing foreign species. There is a broad range of management tools for domestic species, but foreign species' management tools are limited. With foreign species, generally, few ESA or other conservation tools apply. The chief instruments are trade restrictions, CITES trade prohibitions, education and public awareness, and grant monies.

Direct recovery actions are not practical. The Service must balance its duty to protect foreign and domestic species in a way that will not detract from its efforts to protect imperiled domestic species while working with existing resources. The bottom line is that there is insufficient money to go around, and domestic trumps foreign.

The Endangered Species Act mandates that conservation programs of foreign countries should be recognized when based on sound science. Since the Service cannot develop recovery plans for foreign species, priorities for listing or delisting must, by necessity, consider other countries' conservation programs in determining which actions are of higher priority.

But it doesn't.

Human-wildlife conflict in Africa cannot be legislated away, and the biggest threat to any African wildlife species is not poaching. It is to be listed as endangered on the U.S. Endangered Species list.

Comments ()