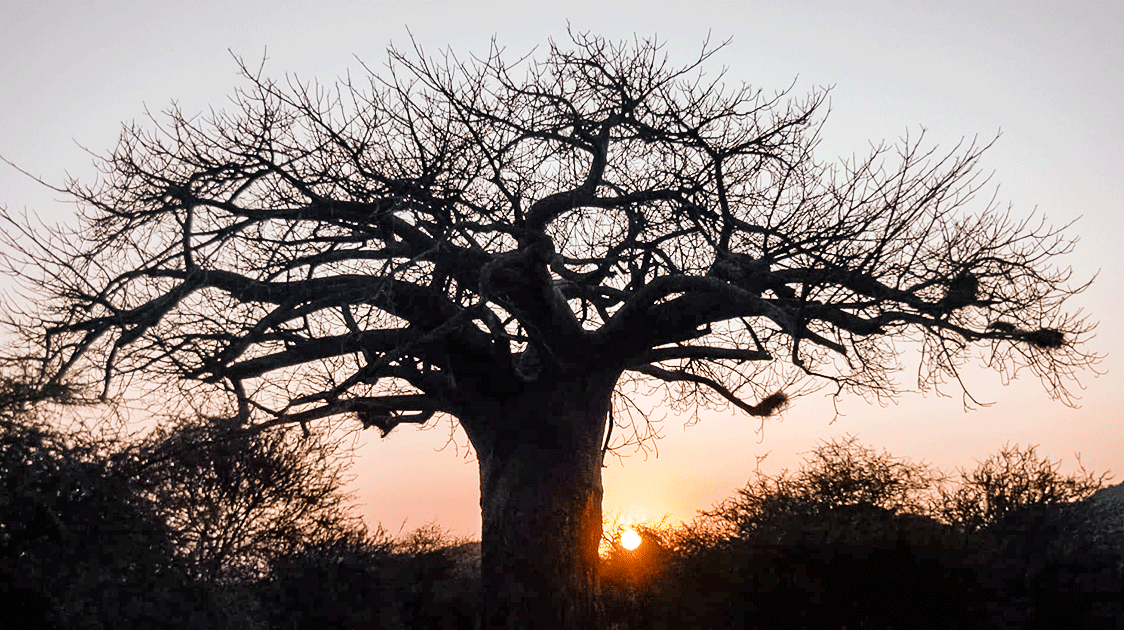

The Evolution of a Wildlife Sanctuary

Zimbabwe's Savé Valley Conservancy has transformed from struggling cattle ranches to one of southern Africa's largest private game reserves.

The Heritage of Ranching

The foundations of what would become the Savé Valley Conservancy stretch back to the 1920s. Roger Whittall's father immigrated to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and initially worked on a tobacco farm in the Umvukwes region. Hearing about abundant hunting opportunities in the Savé Valley, he relocated to Devure Ranch. After years of labor, he established Humani Ranch as a cattle operation.

For decades, the Savé Valley remained prime cattle country, with multiple ranchers, including the Whittall family, operating successful livestock operations.

From Devastation to Innovation

The transformative moment came in 1991 when severe drought, considered the worst in a century, devastated the region. At Humani Ranch alone, 90% of the Whittall's cattle died. Multiple cattle operations went bankrupt, forcing ranchers to sell off their land.

Rather than abandoning the land, Roger Whittall proposed an innovative solution to his fellow ranchers. Having already introduced various game species to his ranch during the late 1960s and 1970s, he suggested converting entirely from cattle to game farming.

Founding the Conservancy

The Conservancy was officially formed in 1992, emerging from this crisis. The Duckworth family joined other ranchers in acquiring some bankrupt sections, while established members like the Whittalls contributed their existing properties.

This coalition of landowners agreed to remove all cattle fences and livestock, creating a unified wildlife reserve.

The Conservancy began systematically reintroducing indigenous game species, deliberately excluding non-native ones. They recognized that to sustain the operation financially, they needed to attract big-game hunters who would pay premium prices.

Plains game alone would have limited the ranch's appeal to safari hunters, which made the acquisition of big game animals essential.

This strategic decision to combine conservation with safari hunting established the financial model that would support all subsequent conservation efforts, including the extensive anti-poaching operations required for the Conservancy's survival.

Elephant Relocation Program

Between 1993 and 1998, the Conservancy relocated approximately 600 elephants from Gonarezhou National Park, which was also suffering from drought. Working with wildlife specialist Clem Coetzee, an innovative capture and transport method to relocate whole elephant herds was developed.

The operation was highly successful, and the elephant population quickly grew to 3,500, exceeding sustainable capacity. The Conservancy has relocated 100 elephants to the Zambezi Valley and plans to move another 400 to relieve the environmental pressure of too many elephants.

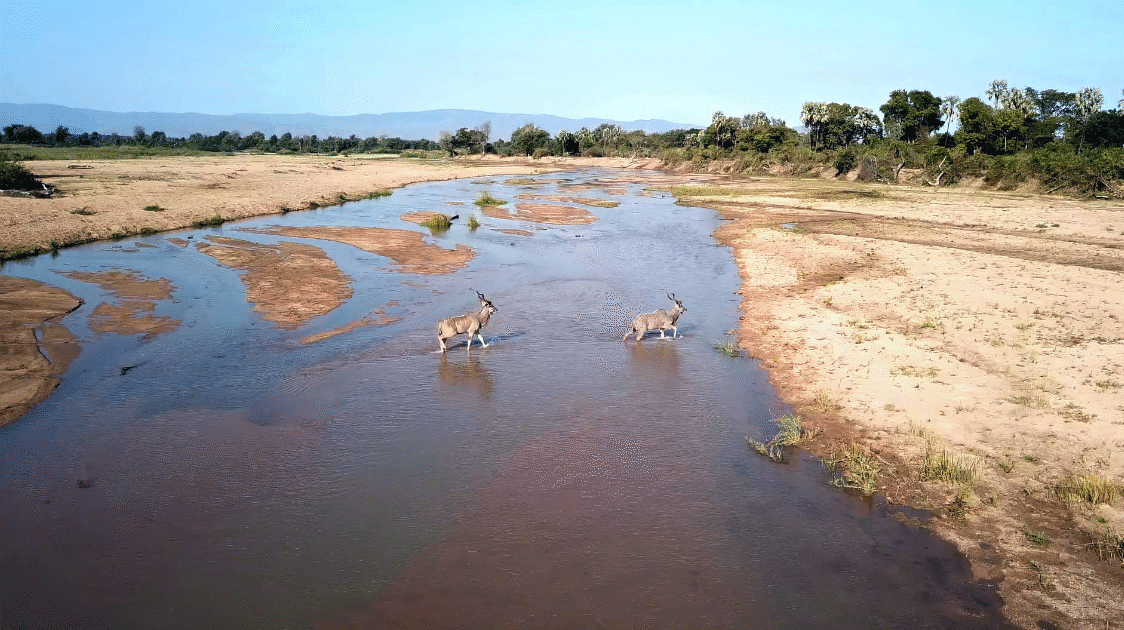

Building Wildlife Populations

The Conservancy established strict foot and mouth disease control measures to introduce buffalo, installing a double, electrified fence around the reserve's perimeter to cordon off the area. 600 buffalo, giraffe, wildebeest, zebra, sable, and nyala were introduced.

Game populations increased significantly through member efforts, including:

- Removal of cattle fences

- Extensive anti-poaching measures

- Elimination of old snares from cattle-ranching days

Predator numbers also recovered, with growing lion, wild dog, and leopard populations.

After the Conservancy's formation and the transition from cattle to game, poaching emerged as a significant threat.

Anti-Poaching Operations

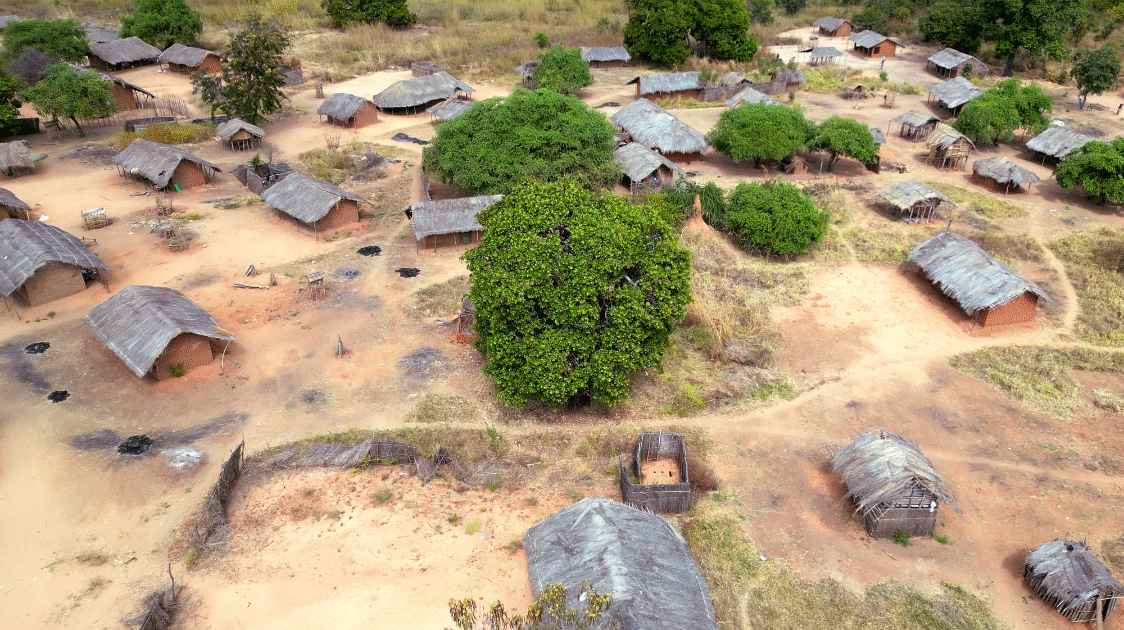

In the 1990s, the human population in the regions surrounding the Conservancy was between 4,000 and 5,000, but today, the number is around 30,000 to 40,000, dramatically expanding the need for land for subsistence farming.

This put severe pressure on the Conservancy, and the land invasions of 2000 marked a turning point.

An influx of settlers saw the Conservancy losing 150,000 to 200,000 acres of prime conservancy land, now predominantly used for agriculture, and a substantial surge in poaching activities.

During the early days of the land invasions, Guy Whittall, Roger's son, reported apprehending 300 poachers annually with only a 10% conviction rate initially.

Since then, the anti-poaching efforts have evolved, and the judicial system has improved, raising conviction rates to 70-80%.

Security Measures

Tsumbei Nemabwe, security manager at Sango Ranch, described how fence destruction allowed elephant incursions into farming areas, resulting in human fatalities. Local communities now request assistance installing electrified fencing for protection.

Anti-poaching scout units conduct daily perimeter patrols, disrupting snares and waiting for poachers to return.

The Conservancy has adopted new tactics, including deploying sniffer dogs provided by Keith Sparks from the Take Action K-9 Unit. The Bluetick hound, trained at the Bubye Conservancy, has proven effective in deterring poachers who typically operate at night with light sources.

These efforts have pushed poachers back 15-20 kilometers from protected areas.

Financial Challenges

Revenue from hunting safaris currently covers essential costs, including vehicles, fuel, personnel, and administration. Without this income, maintaining anti-poaching efforts would be impossible.

The Conservancy aims to establish a centralized anti-poaching unit, which will require funding above what is currently being generated.

Regional Conservation Success

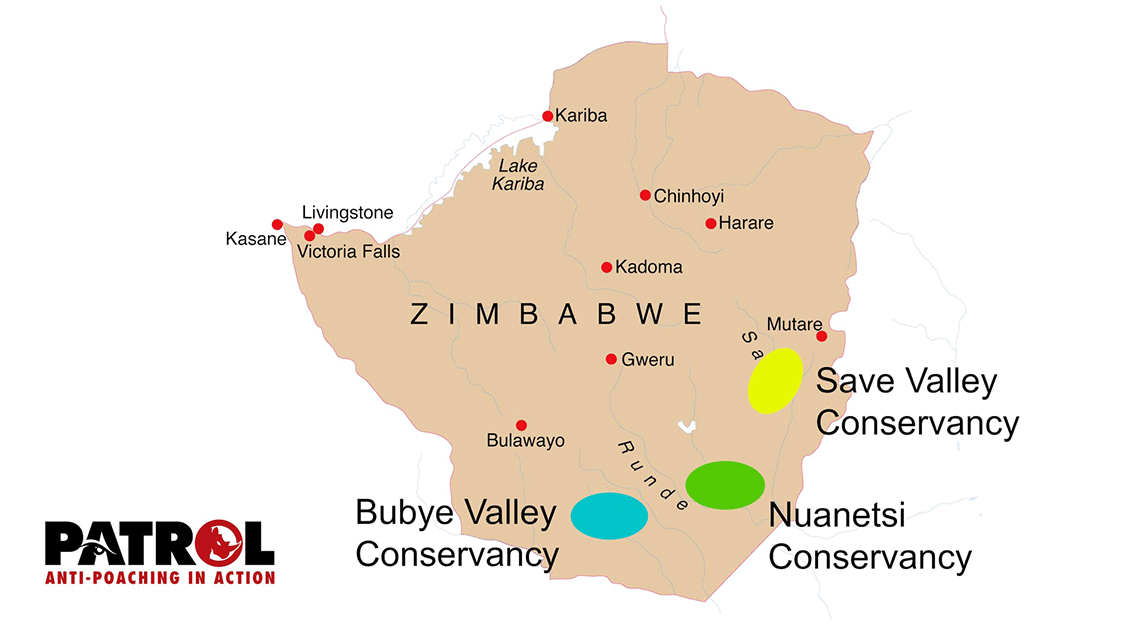

The Savé Valley Conservancy is one of three private reserves, along with Nuanetsi and the Bubye Valley Conservancy, that have achieved notable success through hunting-supported conservation models. It demonstrates potential models for expansion across the region.

These conservancies have effectively increased buffalo, lion, and leopard populations, with Savé Valley maintaining one of the highest leopard densities in the region.

Conservation Vision

The Conservancy seeks to revive the game corridor connecting to Gonarezhou and Kruger National Park, integrating with the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park system.

Addressing existing challenges and securing backing from global governments invested in wildlife preservation remains crucial.

The Conservancy continues balancing community needs, wildlife protection, and economic sustainability through hunting tourism while managing growing elephant populations and preventing poaching.

Click on the links to watch the short documentaries about the Savé Valley Conservancy.

The Savé Valley Conservancy Anti-poaching Operations