Patrolling Smarter, Not Just Harder

By Hank's Voice

To maximize patrol effectiveness, understanding how and where poachers work is essential. Systematically collected, large-scale information on that is sparse, especially in East Africa. But, a recent study by Rija and Kideghesho (2020) in the Serengeti ecosystem of northern Tanzania provided some such knowledge. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43302-4_7

Wildlife crimes are endemic in this ecosystem, with up to 10 to 12% of the wildlife population estimated to be poached annually.

The study focused on the western part of the Serengeti – Mara ecosystem and encompassed four game reserves (Ikorongo, Grumeti, Kijeroshi, and Maswa), IKONA Wildlife Management Area, and Serengeti National Park.

This area's high wildlife densities make poaching an important economic option for the greater than 30 tribes of people living in multiethnic communities in the region.

Although agropastoralism is their typical livelihood, poaching is lucrative and is pursued despite its risks.

The study's conceptual approach was based on Situational Crime Prevention (SCP), which seeks to assess opportunities situations offer for crime. Researchers walking transects mapped poaching evidence, and poachers (convicted and reformed) were interviewed.

They found a widespread distribution of all illegal activities across this ecosystem.

Still, poaching of animals was the most abundant and widespread of all, with a higher incidence of wildlife crimes in the park than in the game reserves.

The following strategies employed by poachers were identified:

CONCEALING EVIDENCE

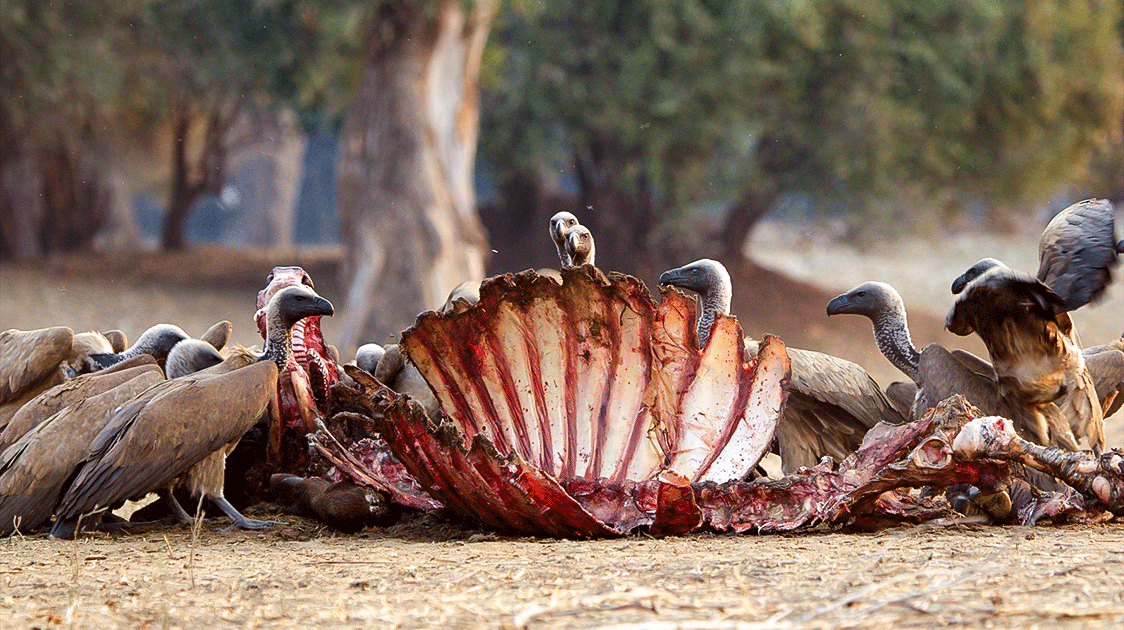

Carcasses are hidden from rangers in trees, burrows, caves, rivers, etc., which also served at times to shun scavengers like hyenas and vultures that could lead rangers to kills. This same evidence also sometimes functioned as potential markers for poachers when they returned to the area in the future.

PLACING HAZARDS ON TRAILS

Sharp objects like nails, pieces of metal, or spears pointing upward, were often placed on pathways intended to wound rangers, forcing patrol delays or suspensions.

Pods or powder of the velvet bean plant (Mucuna pruriens), upupu in Swahili, was also placed where rangers in pursuit might encounter them, causing severe itching.

Some poachers expressed they had a do-or-die approach also, wherein they wouldn't hesitate to face and fight rangers, intending to kill or wound them.

USE OF MOTORBIKES

In the late 20th century, Serengeti ecosystem poachers hunted in large groups with dogs at night, chasing and spearing animals on foot.

Now they use motorbikes, targeting primarily zebra and eland. And they needn't own one, as they often work a profit sharing via borrowing arrangement.

Motorbikes make it easier to supply bushmeat to villages and escape rangers. As an indication of their newfound popularity, motorbike confiscations have more than doubled over the past decade.

DRESSING POACHED CARCASSES WITH INTENT TO EVADE RANGER SUSPICION

Poachers will strip off meat but leave the skeleton intact to mimic lion predation on buffalo and other large mammals.

This also hastens skeletal drying, deterring vultures and diminishing food resources that attract scavengers like hyenas.

POISONING SCAVENGER BIRDS!

Poisoning vultures, especially, has two significant benefits. It eliminates the alert to rangers that a carcass is present, and, once dead, the vulture parts are poached and illegally trafficked, too, as fetishes, traditional medicines, and witchcraft.

NIGHT AMBUSH POACHING WITH PANGAS

Especially when ranger patrols are numerous, quick night trips are made to ambush animals with strong torches. Using pangas (sharp bush knives like machetes), poachers attack animals' spines and hind legs. Once down, they brutally slaughter them. Any that escape are wounded horribly.

CAMPING ON HILLTOPS AND AWAY FROM TRAPPING SITES

It's not uncommon for poacher camps in this area to be greater than 3km away from where they are poaching to minimize detection.

Campsites are regularly changed and abandoned once detected. Typically, they are situated in thick vegetation growing in hilly areas or in places such as caves making it difficult for foot patrols to find them.

OVERNIGHT SET AND REMOVAL OF SNARES

On long poaching trips, snares are left out to catch animals passively. But when poachers detect possible ranger danger, they shorten trips and efforts by targeting sites with high concentrations of game, chasing animals into the snares, and removing all catches and snares in one night. This is done chiefly in areas bordering human settlements, generally within 5km of protected area boundaries.

USE OF MOBILE PHONES

Mobile phone technology and affordability have made scouting and hunt planning with peers, organization of bushmeat porters from villages, and informing peers of ranger presence much easier and quicker than it used to be.

Sadly, phones are also used by some corrupt wildlife officers to communicate anti-poaching plans and locations.

Poaching in this ecosystem is risky. Sometimes even life-threatening. Poachers fear getting caught by rangers and encountering dangerous animals, especially lions.

Getting arrested and sent to jail incurs poachers' higher losses of their previously accumulated money and properties (cattle, farmlands, etc.), and they experience significant deterioration of their household welfare following their absence from their homes.

Some poachers consider this to be the worst consequence of their illegal actions.

With poaching's considerable potential burdens, why do they do it? Primarily because of its economic benefits. An "If we receive pay, we will slay" mindset.

And in the western Serengeti, that revenue can be significant. Many poachers make two to three times more money from poaching bushmeat as infrequently as twice a month than if they were legally employed.

Some interviewed poachers suggested that the best way to address the poaching problem would be for community outreach programs to provide sustainable economic alternatives to convert poachers.

The authors of this study concluded by saying that the ultimate goal of anti-poaching efforts should be to

deter poaching before it happens, which is best accomplished by systematically gathering intelligence to refine and focus patrols.

Simply increasing effort doesn't always increase deterrence. Sometimes it just changes the poacher's routines instead.

By regularly recording and monitoring poaching patterns, anti-poaching units can be spatially and temporally distributed better than just basing patrols on routines or on an as-needed basis. Many routes are based near ranger stations or provisioning areas and are predictable. And lastly, in this ecosystem, rangers should be better equipped to monitor poaching activities at night.

Comments ()